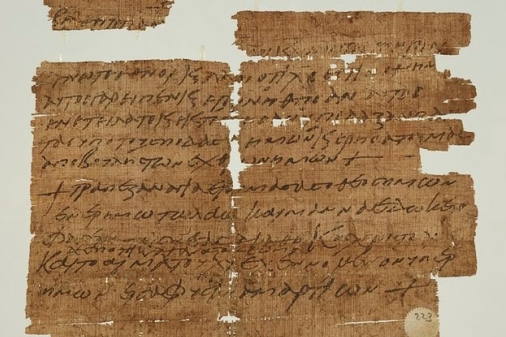

A researcher analysing a 1,500-year-old papyrus tucked away in the University of Manchester's John Rylands Library for over a century has made a startling discovery.

The ancient fragment contains the earliest reference to the Last Supper, a crucial event in the Gospels.

John Rylands Research Institute fellow Dr. Roberta Mazza made the discovery while perusing thousands of unpublished historical fragments.

The papyrus is an amulet containing words that are meant to protect its owners, and Dr. Mazza believes it sheds light on the practices of early Christians.

"This is an important and unexpected discovery as it's one of the first recorded documents to use magic in the Christian context and the first charm ever found to refer to the Eucharist – the Last Supper – as the manna of the Old Testament," she told the Daily Mail.

The text of the papyrus reads:

"Fear you all who rule over the earth.

"Know you nations and peoples that Christ is our God.

"For he spoke and they came to being, he commanded and they were created; he put everything under our feet and delivered us from the wish of our enemies.

"Our God prepared a sacred table in the desert for the people and gave manna of the new covenant to eat, the Lord's immortal body and the blood of Christ poured for us in remission of sins."

The fragment contains extracts from Psalms 78:23-24, Matthew 26:28-30, and other Bible verses.

Dr. Mazza said that early Christians adopted the Egyptian practice of wearing or carrying amulets to protect themselves from harm. Instead of writing prayers to Egyptian or Greco-Roman gods on the paper-like pieces, they wrote extracts from the Bible.

"We can say this is an incredibly rare example of Christianity and the Bible becoming meaningful to ordinary people - not just priests and the elite," she said.

"It's doubly fascinating because the amulet maker clearly knew the Bible, but made lots of mistakes: some words are misspelled and others are in the wrong order. This suggests that he was writing by heart rather than copying it.

"It's quite exciting. Thanks to this discovery, we now think that the knowledge of the Bible was more embedded in sixth century AD Egypt than we previously realised."