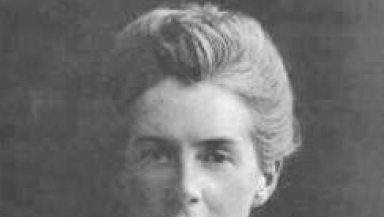

Many Christians refused to wield guns during the First World War, but as Edith Cavell's life shows, this did not mean they were unwilling to fight.

By ensuring that dozens of British, French and Belgian soldiers were able to escape to the neutral Netherlands, she gave a great service to her country. But by working to save the lives of soldiers from a country that would later execute her, she truly showed obedience to what Jesus said were the two greatest commandments.

Edith Cavell was born on 4 December 1865, in the village of Swardeston near Norwich. Her father, the Reverend Frederick Cavell, was vicar to the community for 45 years.

In her early years, she did not much enjoy his style, once writing to a favourite cousin, "do come and stay, but not for a weekend. Father's sermons are so long and dull."

Despite her distaste for her father's preaching, she was very committed to the Church. When money was needed to build a Sunday school room, a young Edith wrote to the Bishop of Norwich.

The bishop agreed to provide some money, provided the community did its part too. To make this happen, Edith and her sister began painting and selling decorative cards. Many sales and a prompting letter to the bishop later, £300 was raised and the Sunday school room was built.

After being home schooled in her early education, she went to three boarding schools in London, Bristol and Peterborough, where she helped other children by teaching them French.

In 1886, she continued this trend of teaching and became a governess, caring for and educating the young children of a vicar in Steeple Bumpstead in Essex.

After inheriting some money, she spent several weeks touring Austria and Bavaria. During this trip, she happened to come across a free hospital run by one Dr Wolfenberg. She was so impressed by the operation that she donated a portion of her inheritance to its upkeep.

This experience would come back to her several years later, but before that she would first spend five years as a governess in Brussels, hired because of her excellent French. Later events would ensure this was not the last she saw of Belgium.

After returning to England, she first cared for her father, before making a life altering career change and moving to become a nurse in London. She worked at first under the pioneering Matron Eva Luckes, who would later receive a CBE.

Although Ms Cavell won an award for her work during a typhoid epidemic, records of Ms Luckes's thoughts of Cavell show she was less than impressed with her. Despite saying she had plenty of capacity, Ms Luckes described Ms Cavell as "not at all punctual".

After her training, Cavell was thought to be good enough for private nursing, but it wasn't where her faith was truly leading her. Looking to work among the most needy, she applied to work in St Pancras Infirmary, a former workhouse which was now a hospital for the destitute. She spent four years there before moving to similar hospitals in Shoreditch and Salford, where she would reach the rank of Matron.

In 1907, Ms Cavell was back in Belgium once more, this time having been invited to train Belgian nurses in the country's first school of nursing. The school, opened by surgeon Antoine Depage, needed an experienced matron who spoke fluent French. Thanks to connections from one of her former Belgian pupils, her name had been put forward and within two years she had a class of 23 students.

The school came to great public attention after Queen Elisabeth of Belgium requested one of the school's nurses to assist her after she had broken her arm. By 1912, the school was providing nurses to schools, hospitals, and nurseries all across Belgium.

When news of the breakout of World War One reached Edith, she was weeding her mother's garden during a visit home to Norfolk. Demonstrating the resolve and humanitarianism she would later be best remembered for, she packed her bags and got aboard the earliest combination of trains and boats she could find that would take her back to her school. Explaining her hurriedness, she told her mother, "I am more needed than ever."

Upon arrival, she sent those who were not fully trained back to their homes, and gathered all the nurses together to turn the school into a hospital that would take care of wounded, regardless of nationality. Their operation was taken over by the Red Cross, and the Germans arrived on August 20.

In autumn 1914, two Allied soldiers came into the hospital. Edith was now put in the middle of a moral dilemma. She was, first and foremost, a nurse and was working under the banner of the Red Cross. Neutrality was their watchword, and their duty was to serve as carers to anyone and everyone first and foremost.

However, she did not see how she could care for these men and then simply hand them over to the occupying German forces, who would surely execute them. Handing these soldiers over to certain death contradicted her medical ethos. After all, what was the point of healing someone's broken leg, only for them to walk in front of a firing squad?

Despite knowing full well that, if she was caught assisting Allied soldiers, she too could be executed, she worked with several sympathetic Belgians, including two aristocrats, Prince and Princess de Croy. Together they formed an underground network which smuggled Allied patients of the hospital into the neutral Netherlands, allowing them to return to England and safely avoid execution at the hands of the Germans.

This system lasted for almost an entire year, during which Edith continued her nursing duties, treating German and Allied soldiers alike with the same diligent quality of humanitarian care. Eventually, she was betrayed by patient Gaston Quien who would later be convicted as a French collaborator. On 3 August 1915, she was arrested.

She was held in St Gilles prison for 10 weeks, the last two in solitary confinement. She confessed to having helped about 60 British and 15 French derelict soldiers escape, as well as around 100 French and Belgians of military age.

The decision to execute Edith was met with great resistance. Even the German Foreign Ministry objected, pointing out the number of German lives she had saved during her work as a nurse for the Red Cross.

But her protection as a non-combatant was, under the first Geneva convention, forfeit because of her decision to be involved in any action specifically aimed at militarily supporting one side. Because the soldiers she helped escape could go on to fight Germany at a later stage, she was considered a member of the army and, as a result, a war criminal.

The British government could do very little. Sir Horace Rowland of the Foreign Office said, "[In Miss Cavell's case] I am afraid we are powerless." Lord Robert Cecil, Under-Secretary for Foreign Affairs, said, "Any representation by us... will do her more harm than good."

The Americans, however, not yet involved in the war, were able to put some pressure on the Germans. Hugh S Gibson, First Secretary of the US Legation at Brussels, made it clear to Germany that a choice to execute Cavell would only further damage their international reputation

"We reminded [German civil governor Baron von der Lancken] of the burning of Louvain and the sinking of the Lusitania, and told him that this murder would rank with those two affairs and would stir all civilised countries with horror and disgust."

However, the reaction in the German high society and the military was less than sympathetic. One German Aristocrat, Count Harrach, said he was disappointed that they did not have three or four English women to shoot.

It was the night before her execution that she spoke the words that have since become the ones most associated with her efforts. Speaking to Reverend Stirling Gahan, the Anglican chaplain who had been permitted to give her Holy Communion, she said: "Patriotism is not enough; I must have no hatred or bitterness towards anyone."

On 12 October 1915, she was killed by firing squad. Her last words were delivered to the German Lutheran prison chaplain, Paul Le Seur: "Ask Father Gahan to tell my loved ones later on that my soul, as I believe, is safe, and that I am glad to die for my country."

Edith Cavell did not just die for her country. She died for the service she offered to all humanity. Her treatment for German soldiers, as well as Allied ones, showed that she stood for something greater than mere national pride.

She truly embodied the spirit of Matthew 5:43-48, where Jesus points out the hollowness of only loving those who love you. Edith's actions to save Allied soldiers from execution were an extension of the same care she offered to Germans suffering as a result of the war.

Allied or German, she wanted to see as few deaths as possible. "I can't stop while there are lives to be saved," she said.