The language of Christian eschatology, of death, judgement, heaven and hell, has by and large, disappeared from the nation's lexicon along with much churchgoing and religious belief. While it is surely a good thing that children are no longer terrorised into proscribed forms of behaviour by threats of eternity in hell, a nation where much of the population no longer understands the language of evil or believes in the reality of sin is proving ill-equipped to respond to a phenomenon such as the Islamic State.

As if to minimise the shock, instead, we give one of the main perpetrators, a British jihadist, a cute nickname, "Jihadi John". What's next? Terrorist Tom, Hamas Harry? Thereby we play the game set up for us by the fanatics who named him and his fellow British terrorists after the Beatles. These are men and women that were somehow grown in Britain. They have exported themselves "over there" but we must take responsibility for the fact that they became what they are in this country. However tempting, we should not desire to kill them back by as painful a process as possible. Instead we should do everything in our power to bring them back here and make them face their families, former friends and most important of all, justice.

The beheadings and the sick justifications for them have woken us up at last, but we still seem at a loss as to what do do. Bewildering impotence and rage hovers at the edges of consciousness, as new media renders us immediately aware, not just of what is happening, but our own powerlessness to prevent it.

Middle East church leaders based in Britain say that the persecutions of Christians in their homelands have been minimised for years. They are particularly critical of some UK churchmen who have in the past portrayed themselves as friends of their churches but who, as word reaches the West of crucifixions, rapes, sex slavery and enforced marriage and divorce, have been strangely silent.

The Archbishop of Canterbury, Justin Welby, is one of those who has been speaking out. He spoke out again today. He admitted it took the West some time to realise how serious the crisis is. "It took the barbarism of Jihadist militants to wake us up," he said. "This is a new thing. There has not been treatment of Christians in this region, in this manner, since the invasion of Genghis Khan."

The 13th century Mongol warlord was renowned for his brutality as he united disparate tribes behind him and seized control of most of Eurasia. Prayers were certainly said by the thousand as he stormed Christian citadel after citadel, raped, plundered, burned and murdered. Prayers did not work for his victims, and unless followed by action, will not work today. The Middle Eastern Christian leaders and their British friends emerged from their meeting at Lambeth Palace vowing that this time, it would be more than just talk. Their intentions are good but on their own, these church leaders have little power to act.

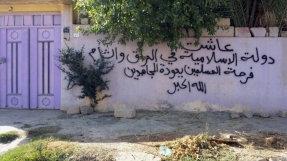

The fear, and the lessons of past wars, the First World War, the Second, of Northern Ireland, Vietnam and Iraq itself, is that it is going to take a terribly long time for any government to achieve anything effective and long-lasting. It might take decades, even longer. In the meantime, Christianity and other faiths are, with terrifying speed, being wiped out in countries where they have existed for millennia, while what replaces them is a barbaric distortion of the 'religion of peace' it purports to represent.

In such horror, prayer is perhaps not such a waste of time after all. Prayer can open our hearts to what we as individuals can do. We might feel powerless but we are not. Britain has not only exported mad jihadists to the Middle East. We also have dozens of aid workers and volunteers in the region, working for Christian Aid, its partners and other NGOs. Christian Aid's Iraq Crisis Appeal is constantly in need of donations. We as individuals can raise funds, and give the money to keep that vital work going. The particular and pressing new hope today is that this Archbishop of Canterbury, perhaps uniquely among church leaders in the West, has the gift of listening, of understanding, and then of being able to make people who do have the power to act, do what needs to be done.