The Death Penalty: What Would Jesus Do?

There's something deeply satisfying, at the most primitive level, when the bad guy gets it. And it's built in to the whole way we're conditioned to think about justice. There's something virtuous about killing. Take the classic Westerns: Audi Murphy plays Destry, the mild-mannered sheriff who prefers to settle arguments without gunplay. But you know he'll shoot the villain in the end, and so he does. Or what about the horrifically bloody but highly entertaining Liam Neeson vehicle, Taken? The father will wade through other people's blood for the sake of his daughter to save her from a fate worse than death, and we tend to approve.

There's something in us that responds to the idea that some crimes are so heinous that those who commit them deserve to die. That's the sense that lies beneath the widespread support for capital punishment, especially in the US. Unless we admit that, counter-arguments won't have any force.

But how we deal with this desire for revenge isn't just about challenging the death penalty: it's about how we respond to every situation where we have been wronged, or where we perceive injustice, or where we've been made angry.

The death penalty, in most countries, is in retreat. Today is the European and World Day against the Death Penalty, and the the EU and the Council of Europe have issued a ringing denunciation of the practice. It is, they say, "incompatible with human dignity. It is inhuman and degrading treatment, does not have any proven significant deterrent effect, and allows judicial errors to become irreversible and fatal."

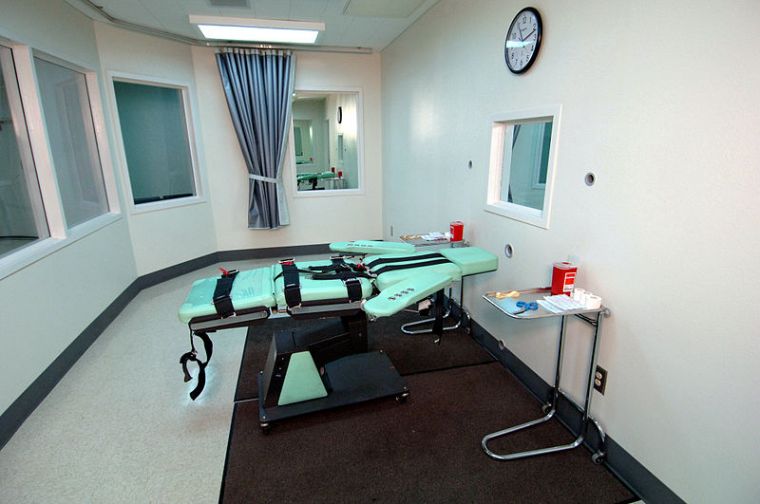

One country where the death penalty is still enforced is the US, the only Western country still to do so. Last year 28 people were executed, though a recent opinion poll has found that for the first time in decades most people oppose it. China, executed more than 1,000 people in 2014; Iran around 750. The West's staunch ally Saudi Arabia killed around 100.

As a policy aimed at reducing crime, capital punishment is pointless. Amnesty International says: "Countries who execute commonly cite the death penalty as a way to deter people from committing crime. This claim has been repeatedly discredited, and there is no evidence that the death penalty is any more effective in reducing crime than imprisonment."

What's left is vengeance, and this is where Christians need to push back – not just in terms of criminal justice, but in how we respond to sin in general.

Capital punishment is fundamentally unChristian because it denies, for ever, the possibility that someone will change. It removes from them the possibility of repentance. It deliberately curtails any chance that they will establish a relationship with God and experience his forgiveness and mercy.

Instantly, the reaction comes: what about those who murder children, or rape, or torture? What about the leaders of countries whose crimes are so vast they are scarcely conceivable? Who wouldn't want to put Bashar al-Assad up against a wall?

And this is where our faith points us to Jesus, who suffered torture and execution, and responded not with revenge but with forgiveness. So to the extent that our reaction to evil is purely punitive, we are less Christian than we should be.

Does this mean we shouldn't punish? Not at all. Whether in our legal system, or our church communities, or our interpersonal relationships, it has to be clear that sin has a consequence. Failure to deal with wrongdoing is failure to take sin seriously, and that means siding with the oppressors rather than with the victims. That's what's happened all too often in the way the Church has dealt with sexual offences against children.

But implicit in punishment should always be the potential for redemption. No matter how grievous the offence and how deep the hurt, the perpetrator remains a child of God. They are not to be dumped or written off. They are not to be cast out from the community. They don't cease to be human beings for whom Christ died, because they have done terrible things. They are not to be executed, because execution is the ultimate denial of grace.

And what challenges us so deeply at the level of criminal justice and institutional punishment challenges us even more deeply at the level of personal relationships. The state has no business with forgiveness; its duty is to protect. But forgiveness is at the heart of Christian faith. We have no business not to forgive, no matter how badly we've been hurt. It might take years; there might never be full healing; we might need to seek God's help again and again in relinquishing our desire for justice; but we are all called to walk that path. After all, God could not be clearer: vengeace is mine, I will repay, he says (Romans 12:19). Not you.

Follow Mark Woods on Twitter: @RevMarkWoods