70 years on, a forgotten tragedy is finally being remembered

Hillsborough, Ibrox, Bradford's Valley Parade... Famous football names all of them. Known for countless Saturday afternoons and weeknights of passion and drama. Yet among the most abiding memories of these renowned footballing venues is the disasters which befell them. The appalling crush at Rangers' Ibrox ground in 1971. The astonishing pace with which the Bradford City fire claimed 56 lives in 1985. The most infamous case of them all – the 96 who went to Sheffield see an FA Cup Semi Final in 1989 and never returned to Liverpool from Hillsborough.

There's another place to add to this sat litany of football tragedies, though. It has lain almost forgotten for the past seven decades. One of the first major football stadium disasters, it took place at Burnden Park in Bolton, Lancashire.

Bolton Wanderers were playing Stoke City, in the Sixth Round of the FA Cup – then the most important club football competition in the world. The Bolton public turned out not only to see their new hero, strapping striker Nat Lofthouse, but also to catch a glimpse of Nat's future England teammate, Stanley Matthews, who was playing for Stoke.

Matthews was a bone fide superstar, the Lionel Messi of his day. In March 1946, less than a year after the end of the Second World War with Britain still on its knees, the glamour of the galactico Matthews proved a huge draw among the dark, satanic mills of Bolton.

No one knows quite how many crammed into the stadium that day, but it's thought around 85,000 tried to get inside. Part of the ground was still out of use, having been requisitioned for the war effort by the Ministry of Supply. It was a recipe for disaster, and disaster ensued on a quite unimaginable scale.

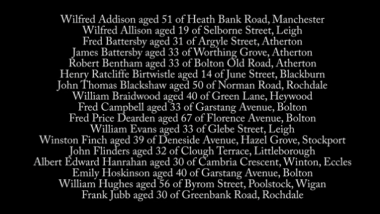

The trouble happened at the end of the stadium which backed onto a railway embankment. There were too many fans in an enclosed space. By the time the match kicked off, the crush had already begun and fans began to spill out onto the pitch. The barriers crashed open and people fell on top of each other. The match was stopped, but it was already too late for many. The bodies began to be laid out behind the goal. Hundreds were injured. 33 were dead.

Incredibly, the match then resumed after the bodies had been recovered.

An incomparable tragedy for the families of the dead, certainly, but very soon it was nothing but a dim memory. Bolton went on to partake in the famous Matthews Final of 1953 against Sir Stan's Blackpool, and won the Cup themselves in 1958, Lofthouse leading the triumph against a Manchester United team recovering from its own disaster at Munich.

By the time I saw my first ever football match at the creaking, old Burnden Park in the late 1980s the disaster was almost never heard of. The 1940s had been tough times – everyone in the country had been touched by the War, so the Burnden Disaster was just one more to add to the list of horrors the British public had endured. A similar fate befell other tragedies such as the Bethnal Green Tube Disaster, which is only now receiving increased recognition itself.

Yet slowly, very slowly, the Burnden Park disaster is being remembered. First came a small plaque, unveiled after the tireless efforts of a widow of the tragedy. Still, to many Bolton fans, it didn't feel enough. Quite rightly, the losses of Liverpool, Glasgow and Bradford are commemorated. Our story just hadn't been told.

Finally, in the past few years, local media began to pick up on the event and revisit those who'd been present that day. Recalling her rescue, 100-year-old Phyllis Robb said, "I don't remember how it started that day but I know they lifted me up and carried me over the top of it all."

To its credit, the football club itself has begun to emphasise the importance of remembering the disaster, not in a showy way, but in a quiet and dignified manner befitting of that wartime generation. A commemorative kit has been produced, without a gaudy sponsor's logo. Fans have been asked to provide their memories, while donations have been made to local charities. The club's chaplain, Phil Mason, has been co-ordinating the remembrance effort.

Today (Wednesday 9th March) at 3pm, exactly 70 years on from one of the greatest sporting catastrophes this country has ever seen, the chaplain will lead fans, ex-players and club staff in a service of commemoration.

Stanley Matthews said of the day, "We heard rumours about the increasing number of casualties yet it was not until I was motoring home that evening that the shadow of the grim disaster descended on me like a storm cloud. To survive a war, only to die at a football match sent a shiver running down the spine of every one of us."

Lofthouse, lionised in the town before and since his death five years ago once said, "Every time I visit the Burnden Park land I can't help but remember the good times we had until that very tragic day. I will never, ever forget." Neither will we, Nat.