80 years after Kristallnacht: Why Jews keep the 'commandments'

What is a mitzvah? Observant Jews are supposed to carry out 613 mitzvot.

Quite a few of the original mitzvot applied purely to the Temple in Jerusalem. Once that was destroyed by the Romans in 70 CE, deeds relevant to the Temple were transformed into studying, discussing and arguing with others about what these deeds and the Temple itself signify.

Even nowadays, some mitzvot can only be carried out in the Land of Israel, but that still leaves Jews in the Diaspora with a few hundred mitzvot that we should carry out daily.

How should we translate this word? Some say it is a 'commandment' (too militaristic in this day and age) and others say it signifies a 'good deed'. But what is 'good' about the mitzvah of the red heifer or not mixing linen with wool?

I often find when trying to translate the seemingly untranslatable that context and cognate languages may help.

So maybe rather than ask what is a mitzvah, we should rather question what is the point of a mitzvah. We are agreed that G-d does not need the mitzvot – He is not the head of an army, ordering us what to do. All we know about G-d is that He exists and has no needs. So the idea of G-d as Brigadier-General in Chief is absurd.

On the other hand, maybe these mitzvot are good for us as humans. Maybe they help us refine our characteristics, change us, encourage restraint and make us more capable of helping others.

Maybe, in addition, the mitzvot help us forge our identity with other Jews. And for some Jews, maybe the mitzvot help us connect with the rest of the world, seeing as we make up such as small part of the global community (0.2 per cent at the last count).

Surely, being Jewish does not simply mean living in tents or ghettoes in which we reinforce our own rather counterintuitive and tight-knit existences. It could also be argued that the mitzvot advocate kindness to animals, and given the right attitude, make us feel happy. Not such a bad thing.

Going further, maybe the mitzvot lead us to a relationship of love for the Divine. King David felt this need which he expresses in Psalm 42, for instance:

'As the deer longs for streams of water, so my soul longs for You, oh G-d. My soul thirsts for G-d, the living G-d. When will I come and appear in G-d's presence?

The sixth Lubavitcher Rebbe, Yosef Yitzhak Schneersohn (1880-1950), leader of the most famous Hasidic sect, related the Hebrew word 'mitzvah' to the Aramaic word 'tzavta' which means 'connection'. And in fact the modern Hebrew derivation of this is 'tzavet', meaning 'team'.

So a person who carries out a 'mitzvah' is connecting with G-d, the issuer of the mitzvah. Maybe this person goes further and attracts others, and so the practice of such deeds and activities grows and has positive repercussions in the wider world.

The popular Mishnaic tome, 'Pirke Avot' 4:2 ('Chapters from the Fathers') states that 'the reward of the mitzvah is the mitzvah'. What does this mean? Surely, that the outcome of a mitzvah is the connection ('tzavta') with G-d, who issued the mitzvah in the first place.

Some people find it difficult in this day and age to understand why Jews bother to observe irrational mitzvot such as not mixing meat with milk dishes, refraining from some foods altogether, defining boundaries in personal relationships and adhering to strict Shabbat observance.

But just bear in mind that for observant Jews these irrational-sounding activities are as important as loving one's neighbour. In fact, for observant Jews, loving your neighbour is impossible without the hints given in the Bible and various commentaries as to how to do this properly.

As the great rabbi Hillel (always admired for his leniency) said in response to a would-be convert who asked him to define what Judaism is, while standing on one leg: 'What is hateful to you do not do to your neighbour. That is the whole Torah: the rest is commentary. Go and study.'

And that's why many Jews spend hours and hours poring over texts that will help them to understand all facets of how to carry out the mitzvot – and the enemies of the Jews know that this is their aim.

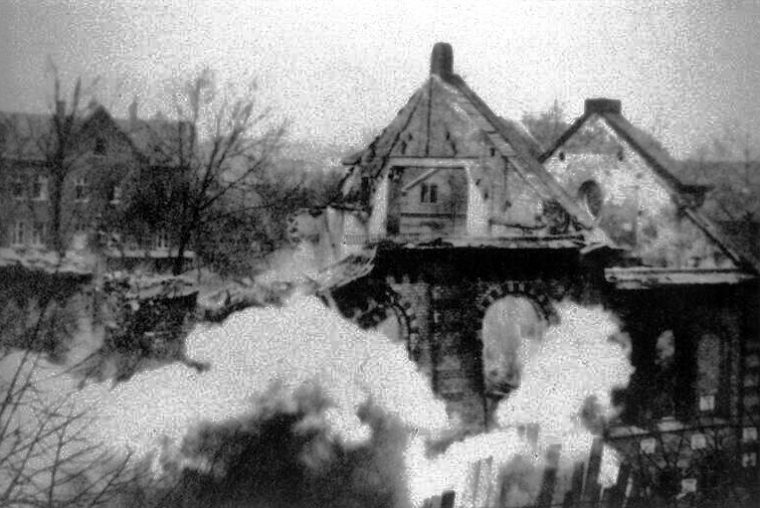

This is why 80 years ago exactly, on the night of November 9-10, 1938, the German authorities together with German nationals carried out Kristallnacht in Germany – the first such pogrom since the Middle Ages. They added caricatures of demonic-looking Jews dancing with or even inside a torn Mishnah or Talmud – one of the books which provides commentaries on the biblical verses regarding the practice of carrying out the mitzvot, which is the way Jews always have connected and will continue to connect to the Creator in order to work in a partnership for the betterment of the world.

Dr Irene Lancaster is a Jewish academic, author and translator who has established university courses on Jewish history, Jewish studies and the Hebrew Bible.