A pilgrimage to the past: Why I'm proud of my awkward spiritual ancestors

As a Baptist, pilgrimage is not really part of my tradition. But some places feel special to me, and on Saturday I visited one of them. Tewkesbury in Gloucestershire, where the rivers Severn and Avon meet, is known for its stunningly beautiful Abbey, and for being the site of one of the battles of the Wars of the Roses, in 1471; that's re-enacted annually, and I'd gone to see the fun.

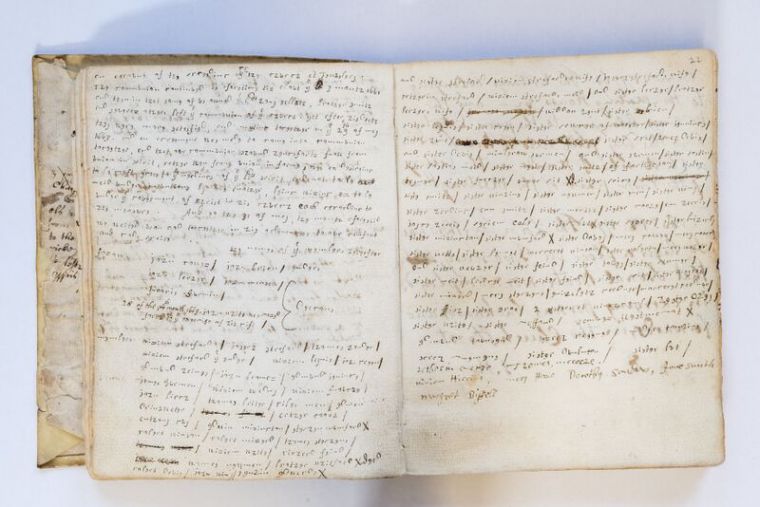

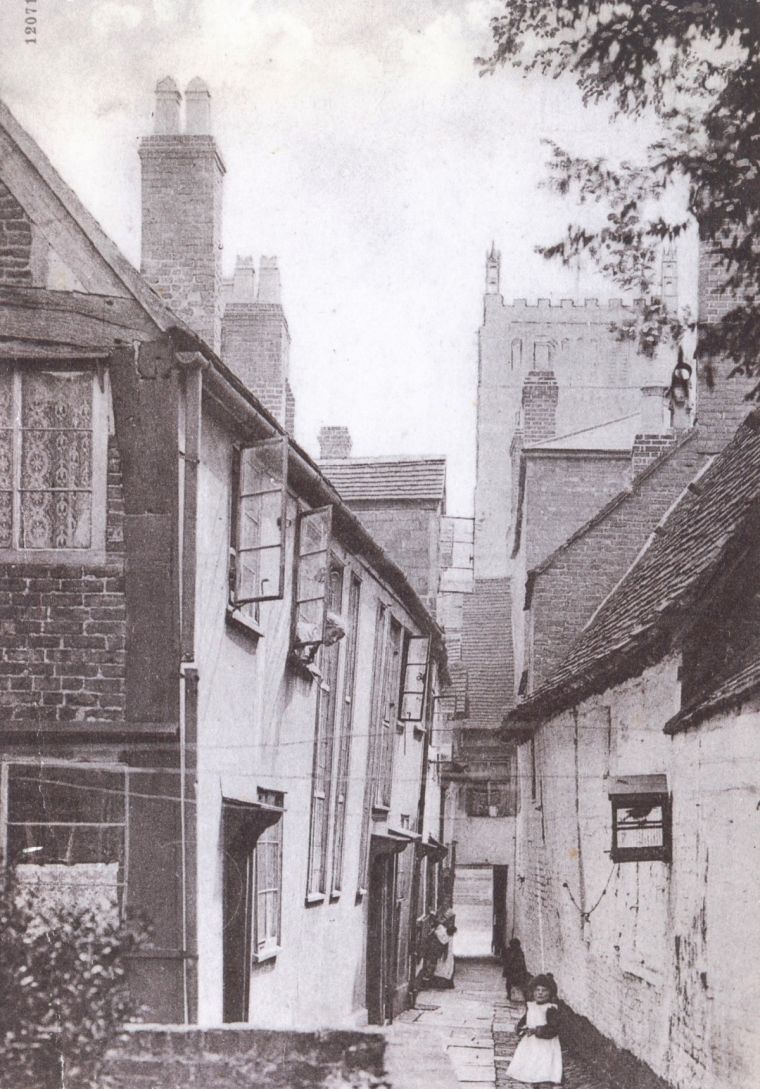

The pilgrimage bit, though, was down a side-street, where you can visit the Old Baptist Chapel. It really is old – a 15th-century 'hall house', just one big room with galleries at either end. It was bought by a Baptist and turned into a meeting-house in the mid-17th century, possibly – the records are unclear – in 1623. If that's true, since that the first Baptist church on English soil first gathered in England in only 1612, this gives it a reasonable claim to be the oldest Baptist building in the country.

It's timber-framed, with wattle and daub. It's been restored to how it was in 1720. There's a lovely barrel-vaulted ceiling to give it more height than the original, a minister's room at the end of one gallery, a brick-lined baptistry dug into the floor and a pulpit in the middle of one of the long walls. There's not much else, apart from information boards telling its story. It's a plain, simple building.

For me, though, the place carries an emotional charge. Because literally a stone's throw away, if you have a good arm, is Tewkesbury Abbey. It's the focal point of the town, at its highest point – useful when the rivers rise and the place floods. It is surpassingly beautiful, inside and out – all green swards, yew trees and clean grey stone on the outside, with polished brass, stained glass and marble memorials on the inside. The contrast between the two places of worship could not be greater.

And it's not just the look of the place, either: back in the 1600s, Tewkesbury Abbey was enormously powerful, economically and politically. Religious tensions were running high, and Baptists were not favoured; Thomas Helwys, who first led them back from Amsterdam, where many English people fleeing persecution at home had settled, was imprisoned by King James I. Anyone publicly rejecting the official Church could expect to pay a price for it, and many were to do so – fined, imprisoned in typhus-ridden jails, beaten, or expelled from their living and their homes.

The contrast between what these Baptist believers left behind and what they chose instead – exchanging the lovely old Abbey for a dark and perhaps crumbling house down a stinking alleyway, knowing the price they would pay but determined to obey God rather than man – is humbling. They were probably awkward customers. They would have had no truck with the sort of cheap ecumenism that airily dismisses doctrinal differences because 'we're all Christians, after all'. For them, what they believed really mattered – enough for them to risk everything for it.

And that's what spiritual pioneers do – they challenge structures, upset apple carts and pay the price.

Would I have been one of them, if I'd lived in those days? I'd like to think so, though they were spiky, difficult people, for whom seeing someone else's point of view wasn't really an evolutionary advantage.

But I'm glad they crossed the road from the Abbey, and I'm proud of my spiritual ancestors.

The Old Baptist Chapel is part of the John Moore Museum. For opening times click here.

Follow Mark Woods on Twitter: @RevMarkWoods