Today marks the anniversary of the death of George Fox, the founder of the Society of Friends, popularly known as the Quakers. The movement he founded has endured as tradition not quite like any other in Christian history. But who was Fox, and what makes Quakers different?

Fox, born in 1624, was raised in a strict religious household, but was an outside at many levels. He was an English Dissenter because he opposed the state Church, the Church of England. He tired of what he called "professors", those with a shallow, superficial faith, and he believed the Church of England to be full of them.

Fox became a wandering preacher with his own Christian message, sharing his ideas about the 'Inner Light' that can guide a Christian's life. As he put it in his journal in 1694: "The Lord showed me, so that I did see clearly, that he did not dwell in these temples which men had commanded and set up, but in people's hearts ... his people were his temple, and he dwelt in them."

Followers of his message became known as 'Friends of the Light', or simply 'friends', and later 'The Religious Society of Friends'.

The group got their name of "Quakers" because the troublesome Fox once found himself before a judge, whom Fox told to "tremble at the word of the Lord". In the eyes of many in society the Quakers were dangerous radicals and they were imprisoned and persecuted across the years.

The Quakers were indeed radical. They emphasised an alternative way of life: they opposed alcohol and promoted manners and simplicity of dress. They were also passionate social activists, preaching peace, social justice, and lobbying for the abolition of slavery.

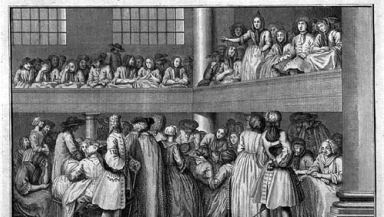

They also had a unique understanding of church gatherings. Quaker meetings had no music, formal ritual, or clergy to lead them. Rather members at the meeting would wait silently for the Spirit to move, perhaps prompting someone to share a word from God.

Their anti-establishment ways meant that many considered them to be blasphemers. One early Quaker leader, James Nayler, was severely punished by Parliament for re-enacting Christ's entry into Jerusalem by riding into Bristol on a donkey: he was whipped, branded on the forehead with a 'B' for 'blasphemer' and had his tongue bored through with a red hot iron.

Fox suffered ill health in his later years and died in 1691. William Penn, Quaker and founder of Pennsylvania, wrote of Fox: "In all things aquitted himself like a man, yea, a strong man, a new and heavenly-minded man."

But what of the Quaker legacy?

They were a key part of businesses that are still influential, such as confectionery companies like Rowntrees and Cadburys. These businesses integrated social justice into their practices, and led the way in transforming labour laws, and marrying profit and philanthropy. Top banks like Barclays and Lloyds were also founded by Quakers and shared their emphasis on ethical, honest business.

Quakers today maintain this emphasis on social justice, particularly a passion for peace, often publicly advocating against war and promoting nuclear disarmament. The Quakers, as pacifists, do not serve in the military. They are deeply committed to social care, prioritising care for society's most vulnerable. Their concern for equality in 2009 led the Quakers in the UK to advocate for same-sex marriage in 2009.

Theologically the Quakers tend to elude precise faith commitments. The Quakers UK website states on its 'faith' page: "Although we have our roots in Christianity, we also find meaning and value in the teachings and insights of other faiths and traditions." They don't advertise any particular creeds, instead simply stating that "there is something of God in everyone".

The Quakers have come along way since the 1600s. They've certainly maintained their "outsider" status, as well as their social convictions about peace and equality, though many would label them as being quite far from orthodox Christianity.

George Fox founded a movement that has endured for more than 400 years and profoundly influenced the world today. He can be remembered as a man who stood for his convictions whatever the cost, and taught Christians to be more than mere "professors" of religion, cultivating instead a deep, still, yet passionate kind of faith.