A portrait of addiction: capturing the humanity of the homeless

Marksteen Adamson spent three years photographing homeless drug addict Alan Dainton before he felt he'd got the perfect shot.

During that time Adamson, an award-winning creative director of a branding agency, spent his spare time photographing Dainton, seeking to capture his 'soul' in a single image.

The photography project proceeded from years of friendship with Dainton. Sitting with him in the street, drinking tea and talking – among other things about their shared struggles with addiction.

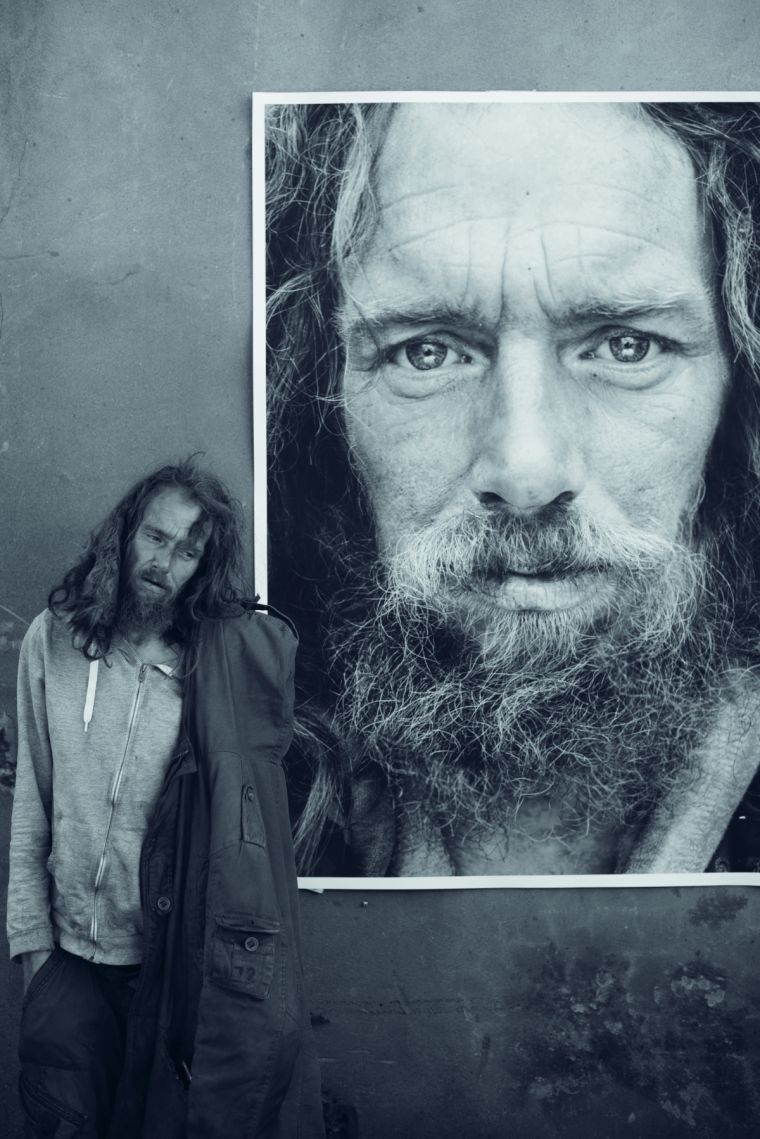

The final product was a triptych entitled 'Behold the Man', an exhibition highlighting the close relationship between addiction and homelessness, which was first displayed at the Wilson Art Gallery in Cheltenham last July.

There is of course a danger that something like this becomes somewhat exploitative – a quest to make an artistic point at the expense of the individual, and it would hardly the first time that Dainton has become the subject of art.

"It took a while for him to see that what I was trying to do was genuine, and that I wasn't trying to commercialise him, because he has been commercialised before," Adamson says. "The amount of students who go up to him and say 'Can I take a picture of you?' and it ends up in an art exhibition, just as 'Here's a picture of a tramp'."

But Adamson's portraits give him a name and a face – and only a face – in the hope of isolating Dainton from his circumstance, history, even his local reputation.

"I didn't want to do 'Here's a picture of a tramp' I wanted to do 'Here's a picture of a human being called Alan, who actually has a soul and is quite stunning, and arresting and beautiful, and has got hidden assets, he just took the wrong turning," Adamson says.

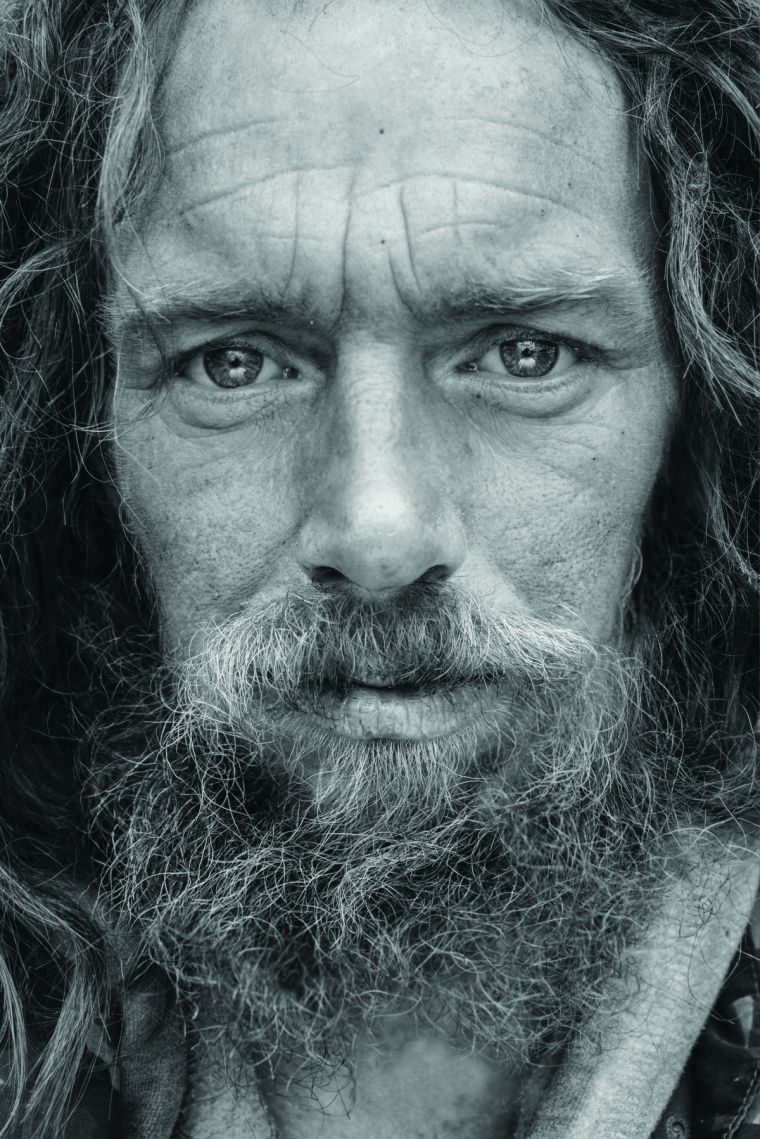

"For me capturing his soul was the day that I would capture him in 'neither nor' – just being," he adds. "It's a hard thing to describe but the Mona Lisa is just being – she's neither smiling, nor happy, nor sad, nor joyous, nor depressed, she just is... With Alan I wanted to get to that point."

Explaining the importance of the size of the image, he says: "If I could get a portrait of him that stripped away all of his context... then blow it up to the size of a human being, I could reverse the idea of significance."

The first image in the series, 'I am', is the sought-after neutral image capturing Dainton's soul without the marks of his current battles. But Adamson says it also makes him think of Christ and the place of contentment that we should all be striving for, instead of chasing happiness in whatever form. After all, it's not merely drugs or alcohol that we can look to in a search for happiness – all manner of things, from caffeine to affirmation, can become addictions that keep us from being content.

Having struggled with addiction in the past, Adamson related to Dainton – at least on one level – as an equal. Though he's far from sharing the pavement and the desperate quest to raise enough money for the day's highs, he has some understanding of the cycle of addiction.

"He saw me, as well as me see him, go through stages of quitting stuff, trying again, relapsing, stopping again... that process of Groundhog Day," Adamson says.

"I've always said to Alan that the reason why I feel for him is that I've always known that at any time I'm only one heartbeat away from being in the same situation, and that is quite a sobering thought."

Adamson acknowledges that there are times when he's been out of control and wrong decisions could have led him down a very different path. He is also aware of the ease with which someone can go from relative security to heartbreak and homelessness.

"When you lose your job, you lose your identity really quickly... you potentially lose your relationship, because respect breaks down; when you lose your relationship, you lose your kids, when you lose all of that you lose your home, and before you know it you've lost everything... addiction does that. It happens quite quickly. People go from being ok, to being not ok in a very short space of time."

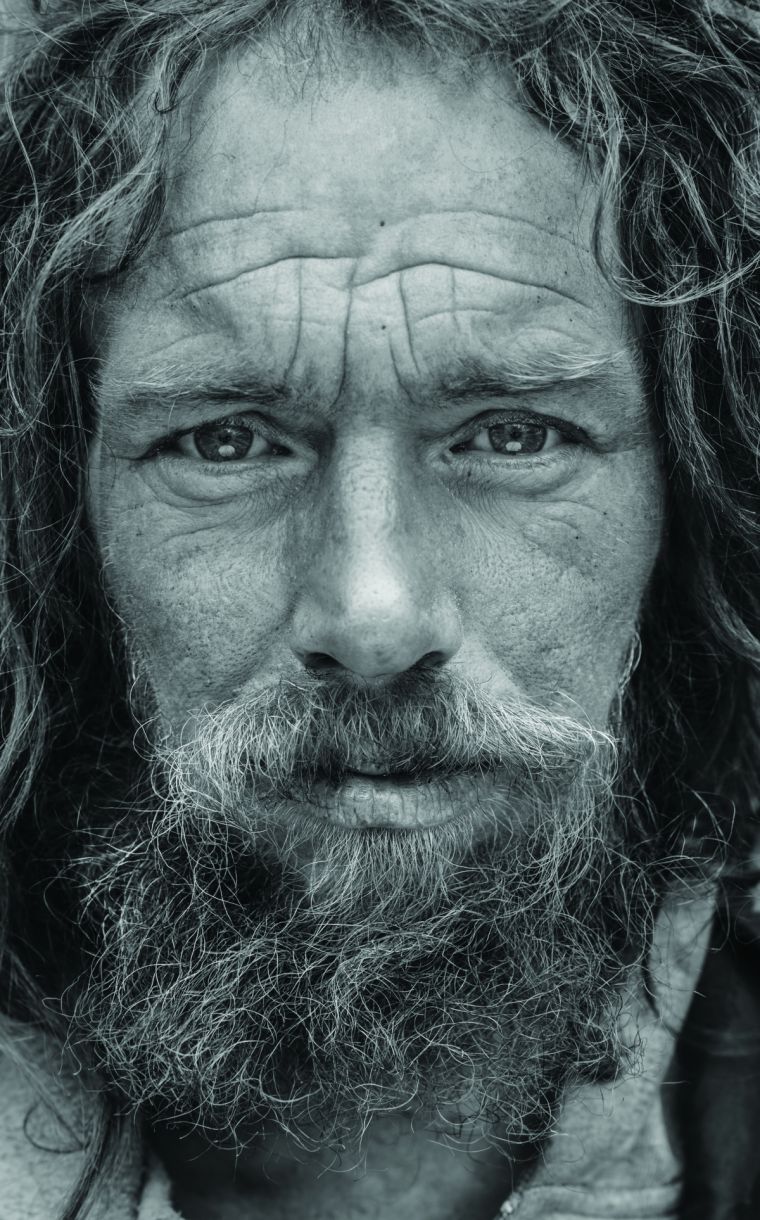

But while he recognises this slippery slope, choice is a central concept in the exhibition. The second image, 'I choose' represents the anxious state of decision making – not just in a journey of addiction, but in all of life's major choices.

Adamson says that while his love for Dainton increased in the time he spent with him, and his empathy remained constant, his sympathy decreased, because he realised that he had chosen to remain as he was. Dainton has been through rehab, but the real choice is when he leaves – choosing to leave behind his old life, or not, as the case may be. At the moment says he's not ready to go back to rehab.

The exhibition in Cheltenham was used as an opportunity to raise awareness among young people of the importance of the decisions they take. The triptych display boards could be inverted for young people to use the blackboards inside to say what they had learned from visiting the exhibition. The money raised from the sale of the books about the project went into preventative measures – efforts to stop young people from becoming homeless in the first place.

The third image shows the effect of Dainton's choice. "I think that's an evil picture, it reminds me of Satan," Adamson says. "He is totally in the grip of addiction. When you're in addiction you can't give, you can only take – hand-outs, steal, abuse, you can't give anything. That is what Satan does."

All three images serve as a prompt for meditation on the choices we make and how we end up where we are. "I don't see everything as just fate," says Adamson. "I genuinely think that I have made wrong decisions in my life, where I've put a lot of work that God have done in my life on hold, and he's ended up using somebody. Yes God has got a plan for our life, but if you carry on going the opposite way, he will use someone else. He's waiting for you to make your mind up."

Adamson spoke to Christian Today at Spring Harvest Christian festival in Minehead, where the exhibition was displayed. The following video documentary was made to accompany the Behold the Man exhibition.

Behold The Man from Marksteen Adamson on Vimeo.