Analysis: As Farron and Brown speak out, can you be a liberal and Christian politician?

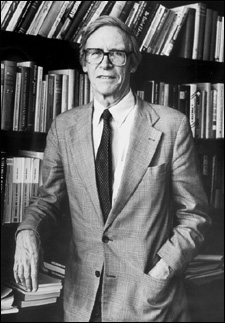

There is a point in Gordon Brown's new book, My Life, Our Times when he cites the late American moral, political – and liberal – philosopher, John Rawls (1921-2002).

In the chapter on faith in the public square, released today and coinciding with separate comments from the evangelical former Liberal Democrat leader Tim Farron, of whom more in a moment, Brown writes that 'people of faith have a duty to use the same tools of reasoning that a person of no faith would use, and to invoke reasons that can be understood and explained at the bar of public opinion, framing their arguments about values in such a way as to include rather than alienate those who do not share their position'.

Brown goes on: 'This is what the philosopher John Rawls meant when he said that in an argument it is right to weigh only those reasons that are part of "an overlapping consensus" of "what reasonable people could be reasonably expected" to endorse. In our public debates we should, he said, appeal not to comprehensive doctrines but to general principles around which there is a possibility of agreement. No matter how strongly felt your religious beliefs, you cannot justify your case for action purely on grounds of faith, and you have to accept that your views are more likely to command authority in the eyes of nonbelievers because they are supported by logic, evidence and an appeal to shared values, than because they have a religious basis.

'You have to argue your case in the public square, submit to scrutiny, acknowledge alternative points of view – and live with the outcome even if your point of view loses out. And that is in line with modern theological thinking: our faith obliges us to use reason, and it is an act of worship to use the brain you have.'

This warning against what would effectively become a tyrannical approach from a religious leader is surely right in a pluralistic society.

It is, arguably, the approach taken by Farron when he was justifying his failure to answer whether gay sex is a sin by pointing to his liberal voting record on gay rights over the years. Ironically, this was not enough, and Farron was effectively driven by a rampantly secular media pack from front-line politics, a temptation Brown warns society as a whole against, too.

All this raises the question of how a politician's faith should impact on their approach to governing.

For to assume that a Christian politician can't be a liberal (with a lower or upper case 'L') is not to misunderstand Christianity, but instead surely to misunderstand the nature of liberalism itself.

But to what extent should politicians with faith adhere to what Rawls called the 'overlapping consensus' when that consensus, especially when it comes to moral and sexual issues, is increasingly secular, at Westminster if not in the country at large? Was Farron right to 'compartmentalise' his faith?

Tony Blair was, of course, famously put in his place by his head of media Alastair Campbell when the latter told an American interviewer, 'We don't do God'. Yet Blair, who later converted to Catholicism, increasingly appears to link his faith to his politics, and Theos, the religious affairs think-tank to whom Farron's remarks will be made this evening, has good form in examining how politicians such as Blair were influenced by their faith on areas such as the ill-fated, White House-driven 2003 invasion of Iraq.

On what are still strictly categorised as 'conscience issues' at Westminster such as abortion, the voting records of most Christian, or certainly Catholic politicians are understandably determined by their faith. This can result in culture clashes, hence the recent liberal outrage over the Catholic Tory backbencher Jacob Rees-Mogg saying that he opposes all abortions even in cases of rape.

But getting away from such issues, and thinking more about what Brown meant when he referred to the 'moral compass' infused in him by his father, a Church of Scotland minister, it is surely right, and arguably even more important, that politicians act in what could broadly be termed a Christian way: doing the right thing even if it is unpopular; compassionate towards the poorest and most needy; concerned about the need for an ethical foreign policy, and much more.

The example of Theresa May's number two, Damian Green, is, perhaps, an unfortunate one to use at this time when he is under investigation by officials for alleged sexual misconduct (which he denies). But he perhaps put it best when, in an interview for The Tablet, the self-proclaimed 'social liberal' and 'birth Catholic' told me: 'There are always going to be areas on which the Church and a party overlap, and areas where they don't overlap...The interaction between the Church and any political party ought to be difficult and I would intensely oppose the idea of political parties being representative of a religion.' On his own approach, Green said of his faith: 'It is so much a part of me that I don't consciously think, "Is this a way to approach a particular political issue?"'

No doubt flawed like us all, Green may prove have fallen short in applying to his approach to politics, and life, a faith that is 'so much a part of me'. But an approach that goes beyond simple voting records on so-called 'Christian' issues such as abortion, and one that extends to all we do, is surely the right one.