Blue tooth: Plaque analysis shows medieval nun illustrated precious manuscripts

Beautiful illustrations that adorn treasured medieval manuscripts might have been created not by men, as is usually assumed, but by women.

That's the conclusion drawn as the result of an investigation into the teeth of a woman – perhaps a nun – who died in the 11th century and was buried in the grounds of a German monastery.

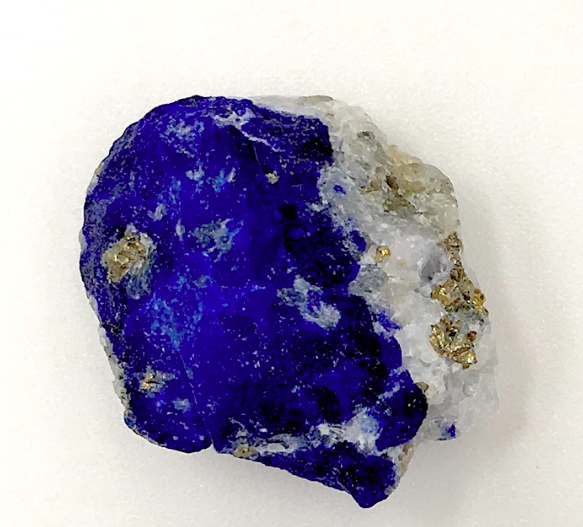

Trapped in the tartar that had built up were tiny fragments of lapis lazuli, a mineral brought from Afghanistan and used to create ultramarine, a deep blue pigment. It was so rare and prized that it was more valuable than gold. The pigment was used in paintings and to decorate illustrations in luxury books of the highest quality, only the most skilled scribes and painters would have been entrusted with its use.

The discovery, made by researchers from the University of York and the Max Planck Institute for the Science of Human History, adds to a growing body of evidence that nuns in medieval Europe were not only literate, but also involved in the production of books.

Researchers suggest the lapis lazuli may have got into the women's mouth as she licked her brush, shaping it to create fine details.

To identify this vibrant blue pigment trapped in the woman's plaque, physicists and archaeologists at the University of York used a range of light and electron microscopy techniques as well as spectroscopy, including a technique called Raman Spectroscopy.

Dr Anita Radini, from the university's Department of Archaeology, said: 'Early scribes and illuminators are largely anonymous and invisible because before the 15th century they rarely signed their work.

'However, the commissioning of talented female scribes to produce manuscripts using expensive and sophisticated methods has precedent, with historical sources from Germany recording the commissioning of a luxury manuscript to be produced by nuns.

'In Germany, women's monastic communities were made up of noble or aristocratic women, many of whom were highly educated. These women would have lived lives free from hard labour and our skeleton fits this profile as it belonged to a middle-aged woman and showed no sign of occupational stress.'