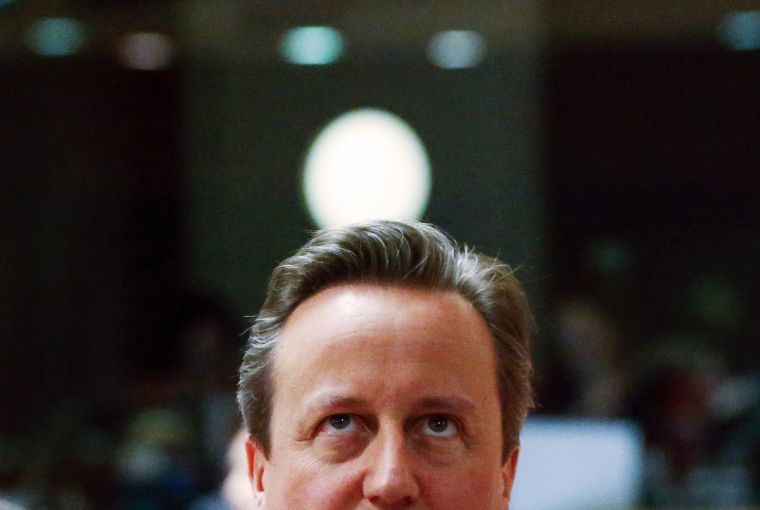

Compassionate Conservatism: David Cameron's failed moral mission

This afternoon, David Cameron will stand up in the House of Commons and announce he still believes in a "modern, compassionate Conservatism".

This is a refrain born in late 1970s US Republican circles and adopted by Cameron in the early years of his leadership when his advisers included Philip Blond, author of Red Tory and Steve Hilton, author of More Human. It informed his widely misunderstood 2010 election manifesto phrase 'The Big Society' but, along with both gurus, the philosophy has been squeezed out over the Prime Minister's rule.

In essence it is the belief that rigorous education, strong families, private sector jobs and individual assets are the keys to poverty alleviation, as opposed to a large welfare state. It was on this belief that Iain Duncan Smith, now a blight on Cameron's premiership, formed the think-tank Centre of Social Justice (CSJ) and set about his self-proclaimed mission of "welfare reform".

Was it a biblical emphasis on family and parables such as that of the five talents which inspired this new wave of Conservatism? It certainly chimes with Cameron's Easter address where he said the Christian message was about "hard work and responsiblity". There were numerous counter-arguments from the left. Many saw the whole idea of compassionate Conservatism as morally bankrupt for advocating reductions on welfare spending for the poorest. Rev Giles Fraser said the compassionate conservatives just made the right "a little bit more left".

Nevertheless many Christians joined those heralding Cameron's election victory in 2010 as a time of great hope for the Conservative party. He was meant to be the great "social reformer" and there was a chance to rebrand the image of "the nasty party".

The whole movement was littered with Christians. Iain Duncan Smith is a Christian alongside his former special advisor Philippa Stroud and Tim Montgomerie, who helped set the CSJ. Christian Guy, who took over CSJ and now works as an advisor in Number 10, also has a strong faith. An evangelical zeal motivated those involved in what they saw as a mission to bring justice to the poor and tackle some of Britain's most deprived areas.

Now over ten years since Cameron was elected leader of the Tories and nearly six since he became Prime Minister, the enthusiasm and excitement have worn off and, some would say, little has been achieved.

There have been occasional reminders of what once was his dominant motif. The 2015 election victory speech promising a "one nation" government was one such example. But evidence beyond rhetoric has been scant.

Cuts to welfare spending were initially hailed as reforms but gradually have seen more and more opposition from Tory backbench MPs. This culminated in the climb-down over tax credit cuts and this weekend's withdrawal of proposed cuts to disability benefits.

However the real reason this philosophy has failed is a lack of real commitment from the party's leadership. Government, Cameron has discovered, brings with it unforeseen pressures. His moral mission of social reform has taken a back seat.

First there was the pressure of running a coalition with all the negotiations and compromises that entails. There was also the disappointingly slow rate of economic recovery which meant less money to play with. And ultimately there was the growing threat of UKIP to his core Conservative base with the defections of Douglas Carswell and Mark Reckless especially prominent.

A combination of these factors has seen compassionate Conservatism marginalised. No where is this more evident than his fabled "family test". Meant as a means to judge the impact of every new policy on families, it was seen as part of the compassionate Conservative's emphasis on strong families as key to tackling poverty. But the difference between rhetoric and reality is pronounced. On the shockingly few occasions the family test has been published, it has been little more than a tick box with no evidence that it has any impact on decision making. Social reform has just not been a priority. And now it seems it has come back to bite him.

When the Prime Minister re-declares his commitment to compassionate Conservatism to MPs this afternoon his pledge will ring hollow. He has had six years of governance to demonstrate that commitment. And as yet little to show for it. A series of "life chances" speeches over the past few weeks suggest that, in an ideal world, Cameron would still like to deliver his social reforms. The problem is they are little more than a nod to his legacy and he turns his eye to life after number 10. They are not defining parts of his leadership.

There are many within the Conservative party who still believe in the "big society". Stephen Crabb, the new work and pensions secretary, is one example. If, as some are suggesting, Crabb's promotion is the start of his campaign to be next Tory leader, then compassionate Conservatism could well not be not dead yet.