Ask anyone who the greatest defender of the faith in the 20th century was and they would probably, after a bit of thought, suggest it was CS Lewis. Lewis was was a giant; a true intellectual who had the gift of being able to talk to ordinary people – and he was a great storyteller, too.

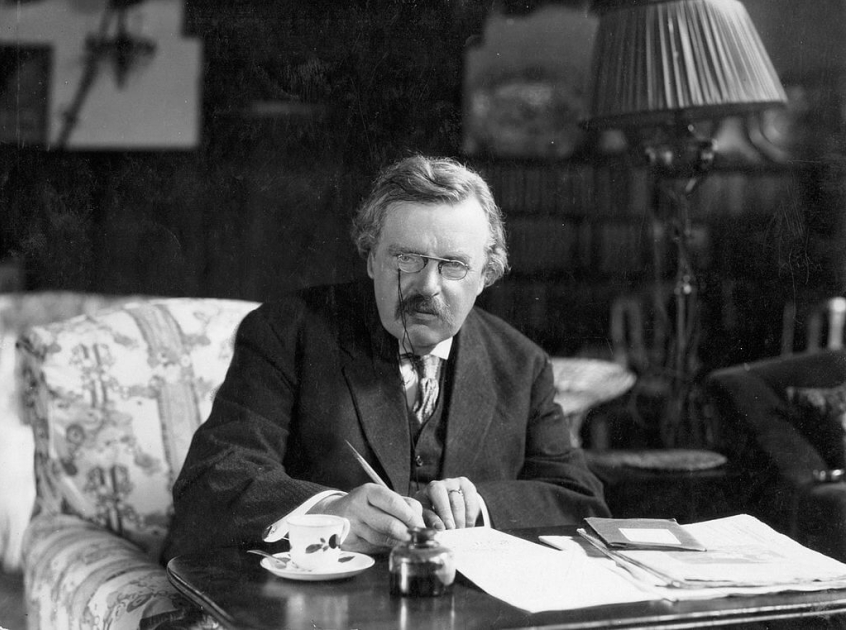

But Lewis always paid tribute to his predecessor, a man equally gifted and just as influential. GK Chesterton (1874-1936) was also intellectually brilliant. He also worked constantly, and quickly; it's been suggested he was one of the most prolific writers of all time. What he would have done with a modern computer is anyone's guess.

Born in London, he was educated at St Paul's and then studied art. A Roman Catholic, he found his calling in journalism when asked to contribute magazine articles on art criticism. He wrote more than 100 books and contributed to 200 more, hundreds of poems including the thrilling Lepanto, five plays, five novels and hundreds of short stories including many featuring his famous priest-detective Father Brown, who is regularly brought to the small screen.

He wrote more than 4,000 newspaper essays and edited his own paper, G.K.'s weekly. He read vastly in literature, philosophy, theology and Church history. Physically imposing at over six feet tall and 300 pounds in weight, he was famously absent-minded (he once telegraphed his wife, "Am at Market Harborough. Where ought I to be?"), wore a cape and carried a swordstick. He was witty, generous and kind.

He was also thoroughly Christian, and made the case for Christianity in all his work. Lewis paid tribute to his book The Everlasting Man, calling it "The best popular apologetic I know." He says Chesterton influenced him to become a Christian: "In reading Chesterton, as in reading [George] MacDonald, I did not know what I was letting myself in for. A young man who wishes to remain a sound atheist cannot be too careful of his reading. There are traps everywhere."

What marks Chesterton out as a prophet for our time? One admirer, Dale Ahlquist, writing for the American Chesterton Society, puts it like this: "Chesterton argued eloquently against all the trends that eventually took over the 20th century: materialism, scientific determinism, moral relativism, and spineless agnosticism. He also argued against both socialism and capitalism and showed why they have both been the enemies of freedom and justice in modern society."

Chesterton, he says, defended "the common man" and common sense. "He defended the poor. He defended the family. He defended beauty. And he defended Christianity and the Catholic Faith." It's because these don't play well in today's public arenas, says Ahlquist, that Chesterton isn't always given his due.

Take just one example: Chesterton on the family. In a collection of essays drawn from his Daily News columns and published as What's Wrong with the World, he writes of 'The Free Family'. Chesterton says: "It may be said that this institution of the home is the one anarchist institution. That is to say, it is older than law, and stands outside the State... This is not to be understood as meaning that the State has no authority over families; that State authority is invoked and ought to be invoked in many abnormal cases. But in most normal cases of family joys and sorrows, the State has no mode of entry."

He means that the law simply has no influence over what really matters in family life. "If a baby cries for the moon, the policeman cannot procure the moon – but neither can he stop the baby. Creatures so close to each other as husband and wife, or a mother and children, have powers of making each other happy or miserable with which no public coercion can deal... The child must depend on the most imperfect mother; the mother may be devoted to the most unworthy children; in such relations legal revenges are vain."

The family really is the bedrock of society, he argues. So he also believes that what was then called 'free love' is a damaging illusion. The sexual bond, he says, is like the "second wind" in walking: "In everything worth having, even in every pleasure, there is a point of pain or tedium that must be survived, so that the pleasure may revive and endure... all human vows, laws and contracts are so many ways of surviving with success this breaking point, this instant of potential surrender." The institution of marriage is there to help people through this. "Coercion is a kind of encouragement ; and anarchy (or what some call liberty) is essentially oppressive, because it is essentially discouraging."

Referring to the ease of divorce in the US, he writes: "If Americans can be divorced for 'incompatibility of temper' I cannot conceive why they are not all divorced. I have known many happy marriages, but never a compatible one. The whole aim of marriage is to fight through and survive the instance when incompatibility becomes unquestionable. For a man and a woman, as such, are incompatible."

It's this kind of robust common-sense and willingness to challenge received wisdom – and his resolute challenge to the power of the State, as well – that's the mark of Chesterton's mind. He attacked capitalism and socialism, the aristocracy and the dictatorship of the proletariat, with the same shrewd insight. He believed God had spoken through the Church to the world, and it was his job to tell people what He had said.

And perhaps the most important lesson for many modern-day defenders of the faith is that he did it with such good humour and warmth that he was universally loved. CS Lewis, who read him while he was still an atheist, wrote in Surprised by Joy: "His humour was of the kind I like best – not 'jokes' imbedded in the page like currants in a cake, still less (what I cannot endure), a general tone of flippancy and jocularity, but the humour which is not in any way separable from the argument but is rather (as Aristotle would say) the 'bloom' on dialectic itself. The sword glitters not because the swordsman set out to make it glitter but because he is fighting for his life and therefore moving it very quickly... Moreover, strange as it may seem, I liked him for his goodness."

As one of his opponents, George Bernard Shaw, said: "The world is not thankful enough for Chesterton."

Follow Mark Woods on Twitter: @RevMarkWoods