Earliest draft of King James Bible found in forgotten notebook

The earliest known draft of the King James Bible appears to have been discovered inside an old notebook at a Cambridge college.

An American scholar, Jeffrey Miller, made the discovery among a collection of forgotten papers at Sidney Sussex College.

Miller, an assistant professor of English at Montclair State University in New Jersey, explained how he leafed through a notebook belonging to Samuel Ward, one of a team of seven in Cambridge translating disputed passaged for the King James Bible. As he flicked through the pages he noticed verse-by-verse biblical commentary with "Greek word studies, and some Hebrew notes" and tried to work out from where in the Bible they came.

"There was a kind of thunderstruck, leap-out-of-bathtub moment," said Miller. "But then comes the more laborious process of making sure you are 100 per cent correct."

"The true value of Ward's draft, though, lies less in the sheer fact of its uniqueness, and more in what the draft, in its uniqueness, helps to reveal about one of the seventeenth century's most extraordinary cultural achievements," Miller told the New York Times.

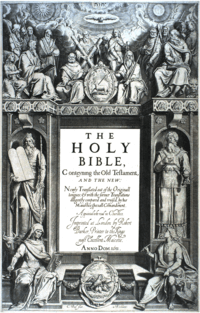

The King James Bible, published in 1611, is considered one of the great achievements of modern English literature. Commissioned by King James I in 1604, the work was completed by different teams of translators, known as companies. It was designed to be an authoritative version to support the Church of England against the Puritan influences on the text of some earlier translations.

Written in poetic language, it was meant to be read aloud and has been heralded as one of the most influential books in the forming the modern English language. Many common phrases and idioms such as "salt of the earth," "den of thieves," "fight the good fight" and "the skin of my teeth" have their origin in the King James Bible.

However until now little has been known about how the translation was put together. The four companies were asked to do their work as a group, rather than subdividing the work among individuals as was the case with previous translations.

Ward's notebook, however, shows an individual scholar's struggle with aspects of the Greek and Hebrew text. This suggests, Miller said, that the King James Bible may be less the work of committees than previously thought.

"The King James Bible, in short, may be far more a patchwork of individual translations – the product of individual translators and individual companies working in individual ways – than has ever been properly recognised," he said.