Election 2017: Visiting Wheatley, the Tory stronghold where Theresa May grew up in a vicarage

It is intercessions time during the mid-week Communion service at the Victorian church of St. Mary the Virgin in Wheatley, and we are praying for 'all candidates' in next week's general election.

For one in particular, standing to be re-elected as Prime Minister, this is a special place: Theresa May grew up as a teenager in and around this church, where her father Hubert Brasier was vicar from 1970-1981. While still in post, Brasier died in a tragic car accident and his grave can be found at the east end of the churchyard.

Today, the congregation at this relatively 'high' church is literally three people and a dog (Tessie, a black rescue labrador). But May needs all the prayers she can get as the Tories appear to be faltering – from being in line for a landslide when she called the election on April 18, to today, when one YouGov poll suggests that there will be a hung parliament.

Wheatley, a sprawling, sleepy and quintessentially English village in the heart of Oxfordshire, lies in the Henley constituency, one of the safest Tory seats in the country, previously occupied by Boris Johnson and Michael Heseltine. Today, Henley's MP, John Howell, enjoys a majority of 25,375.

But that does not stop local Tory-minded residents being worried by the way this campaign has gone – after awkward encounters with the public and gaffes and U-turns by May on the so-called 'dementia tax' and social care – with only a week to go until polling day.

Inside the church, its incumbent vicar, Nigel Hawkes, is very reluctant to talk about politics, saying 'I minister to people of all persuasions.' But asked what his advice is to voters, including the 70 or so who turn up on Sundays here, he tells Christian Today: 'My advice is for them to read the Archbishops' letter,' referring to the election message released by Justin Welby, the Archbishop of Canterbury, and the Archbishop of York John Sentamu. 'It's a very good letter, and encourages us all to engage with the political process, and prayerfully consider how to cast our vote.'

In 2014, May told BBC Radio 4's Desert Island Discs of her upbringing at the vicarage next to this church, consecrated in 1857: 'Obviously everything did revolve very much around the church. Early memories of a father who couldn't always be there when you wanted him to be, but he was around quite a lot of the time and other times when other parents weren't normally. I have one memory for example of being in the kitchen and looking up the path to the back door where a whole group, a family, that had come to complain about an issue in the church and that's it, just knock on the door and expect to see the vicar.'

Back then, she told the same programme that faith does guide her, but added: 'It's right that we don't flaunt these things here in British politics.' It was an echo of when Alastair Campbell famously interrupted an interviewer questioning Tony Blair, and said, 'We don't do God.'

But since then, May has increasingly talked about her faith and the importance of the sort of 'Christian values' with which she grew up here.

Even today, she told Premier: 'I continue to practise in the same way that I always have done and I think it's important that one is able to do that. Faith guides me in everything I do.'

So what do the ordinary folk of Wheatley make of these values, and of her chances next week?

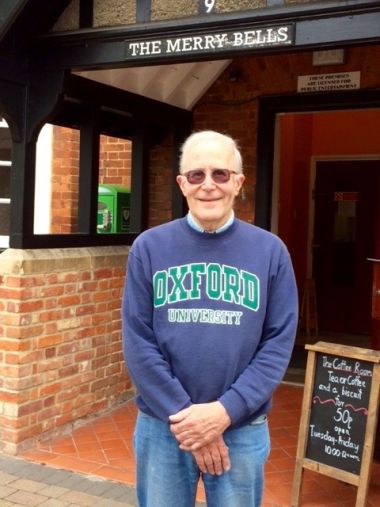

Away from the church, not all are interested in faith here. Outside the parish office, Paul Hurd, 73 and like many here a former worker in the automobile industry, says he will 'definitely' be voting Conservative, though he is 'not at all' interested in 'Christian values' or the fact that May is a vicar's daughter. Instead, he says, referring to last week's suicide bombing in Manchester, 'religion is the biggest cause of trouble mankind has known – everything bad at the minute seems to be in the name of religion'. He voted for Brexit last June and simply believes that the Tories 'are the only ones who can do the job' of delivering on leaving the EU.

But down from the church on the high street, 71-year-old Martin Brook remembers May's father, 'Hugh', because he married Brook and his wife in the church Eileen back in October 1970 when he first moved here. He recalls being invited into the vicarage and being struck that the small family – May was the only child of Brazier and his wife Zaidee, who sadly died a year after her husband after suffering from multiple sclerosis – owned a small, black dog with only three legs. Brasier was a 'very pleasant chap' who walked with a stoop, 'very calm, quiet, a gentleman'.

Brook says he will 'probably vote Tory' next Thursday, and agrees about the importance of the 'Christian values' of which May increasingly talks. 'Oh yes, definitely – Christian values are very important, how you treat your fellow man, how you treat each other with respect.'

He does say, however, that such values are 'not exclusively Tory – they can't corner the market' and he adds that 'Labour and the green party have Christian values,' too. 'What I don't like,' he says, 'is when Christian values are pushed to one side so as not to offend people – political correctness and all that.'

Sylvia Street, also retired, similarly attends and sings in the choir at St Mary's, which she describes as 'a very friendly' church. She also votes Tory but is 'getting a bit concerned' by the polls.

She's not the only one. 'This is a lot closer than we thought it would be,' says Alan Beresford, sipping a lunch-time glass of Sauvignon in the Kings Arms. May has made a hash of social care and taxing pensioners, he thinks. 'I thought the Tories would walk it. They should have walked it but they have made every single error you can think of.'

Some support for other parties is evident in Wheatley, to be fair. One of the congregants at the Communion service was a Liberal Democrat voter who preferred not to give her name, but said quietly: 'Christian values are best lived out in our individual daily lives,' away from politics.

Another tentative talker is 26-year-old Chelsea Davies, one of the few young people evident in the village during this half term week in which some families are away. 'I'm not keen on the lady that comes from here,' whispers Davies, speaking outside the Ochre cafe in which she works. 'She frightens me a little bit if I'm honest with you. She's ready to look after a certain...class of people...We live in a village that is surrounded by Conservatives and if you say the wrong thing you get daggers.'

Like many of her generation, Davies voted Remain in the EU referendum and is now set to vote for Jeremy Corbyn. She moved here from Enfield in London three and a half years ago and says 'it's lovely village to live in' but says that she hopes Labour will win and 'I don't really tell anyone [that] around here'.

More open in his support for the official opposition is John Fray, 73, who invites us into his home which is adorned with a large Labour poster. A trade union man, he is a former deputy general secretary of the National Union of Journalists who, like many people here, cites the cost of housing as the main issue in the largely wealthy constituency. 'It continues just to increase, which is why lots of young people simply cannot afford to buy,' he says.

Fray, who joined Labour 42 years ago, is delighted by Corbyn's leadership and the shift of power in the party from what he calls the 'Tory lite' wing of Labour to the membership. He says the Lib Dems – who were pushed into third place here in 2015 – were 'crushed' by their coalition with the Tories, and claims that there has been 'an incredible rise in Labour membership in this area' which he puts down to Corbyn.

While he accepts that Labour won't win here, he says that the so-called 'dementia tax made a massive difference in people's thinking. The vast majority of my generation believed that they'd paid in most of their lives to be taken care of...of course it's not just those who are ill and needing looking after – it's the families, too'.

On faith, Fray claims that 'Jesus was the first socialist – he threw the moneylenders out of the Temple' and 'Christians wouldn't press the [nuclear] button...Theresa May goes to church on Sunday ready to press the button on Monday'.

Perhaps more representative, also talking to us at her home, is Anne Davies, the chair of the parish council. Though she votes Conservative, she is less partisan, and says: 'Whatever party you belong to, there is a feeling of being proud of the fact that the Prime Minister lived in this village.'

The issues for the village are, she says, 'the same for most villages on the edge of large towns – pressure on housing...a huge demand on new homes' and the relocation of the Oxford Brookes campus, which is situated a mile away and which brings even better bus links to an area well served by public transport to Oxford, London and more locally.

She attends St Mary's on and off, and says in the context of May's religion: 'I personally don't think it matters what someone's faith is – as far as I understand it, I don't think she's been preaching.'

Reflecting on the area, the Bishop of Buckinghamshire, Alan Wilson, says of villages like Wheatley that 'pockets of poverty can emphasise the contrast between your life and the lives of others. Seemingly affluent areas can become very unbalance communities. It's not all green and leafy.'

He recalls Hubert Brasier, May's father as a 'nice man'. '[He] was well known in the Oxford diocese when I was ordained there. He was well-respected — a good man, old school, a bit uptight perhaps but a much loved Anglo-Catholic parish priest. Theresa May remembers having to wait for Christmas presents because her dad was out visiting the poor – he was very dedicated. But it won't do to excuse policies that savage public services by claiming a public service ethic as a vicar's daughter – very much part of Theresa May's "package".'

Turning to the meaning of 'Christian values,' Bishop Wilson adds: 'For me the ultimate Christian value is Jesus Christ. To try to claim a monopoly on public virtue for any religion is fraudulent. There are distinctive Christian values but they are very radical – giving in order to receive, dying to live, the first being last and the last first, the child being the greatest in the Kingdom of Heaven. But I don't see politicians saying these things.'