Evangelical victimhood: Why we should challenge the narrative

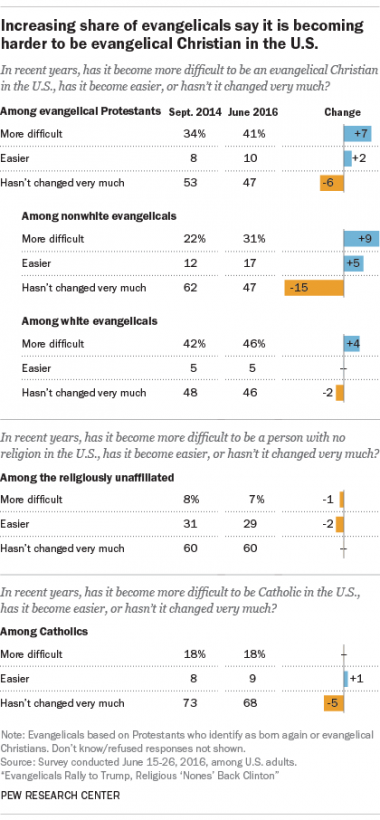

Is it really harder to be an evangelical Christian than it used to be? They think so in the US, certainly. According to a Pew Research survey, 41 per cent of 'evangelical or born-again' Protestants say it is. This marks a considerable leap since the same question was asked in 2014, when only 34 per cent said so.

The figure for white evangelicals is consistently higher (46 per cent compared to 42 per cent in 2014), but it's up for non whites as well, to 31 per cent from 22 per cent.

It's easy to see what's made the difference: the decision by the US Supreme Court to effectively legalise same-sex marriage. This was a shattering blow to evangelical social conservatives who'd elevated it into a struggle for the soul of the nation. The implications are still being worked out in anti-discrimination court cases up and down the land, each of which generates publicity for the cause.

Couple this with the ongoing struggles over the Obama administration's transgender bathroom law, and the evangelical narrative that it's harder to have faith strikes ever-deeper roots.

Whether it's true depends on what you mean by evangelical. It's no harder to preach the gospel of salvation in Jesus Christ. Christians are entirely free to do that. But among many evangelicals – not by any means all – that message has become identified with a socially conservative, imperialistic agenda that's perceived as seeking to impose a particular set of behaviours on an entire society.

And it's patchy, but like it or not, most Americans are basically OK with LGBT people having equal rights and transgender people being allowed to live without facing hostility and discrimination. How that works out in practice is debatable – and debated. But Christians need to be very sure that when they say it's harder to be an evangelical, they aren't just saying "It's harder to discriminate against gay people" or "It's harder to get away with saying hateful things about transgender people."

America, like the UK, is living in an in-between time, when the old consensus about right and wrong has vanished and a new way of ordering relations between the Church and society has yet to emerge. The only certain thing about it is that the die-hard culture warriors will lose.

But whether evangelicals are right or wrong in their beliefs isn't the most interesting question about Pew's findings. There's another perspective that holds for evangelicals on both sides of the Atlantic, and it's that the sense of being embattled victims, surrounded by the forces of godless liberalism, actually works in our favour.

A just-published book by Andrew Brown and Linda Woodhead, That Was the Church That Was: How the Church of England Lost the English People, makes the point rather well. In a chapter entitled 'A brief theory of religious decline', Woodhead draws the distinction between 'societal' churches like the CofE, embedded in society at every level, and 'congregational' ones that find their identity in opposition to society rather than within it. "Societal churches are sustained by the sense that they reinforce society; congregational ones by feeling in conflict with it," she says.

Woodhead puts the decline of the CofE down to the congregational approach becoming dominant as the Church lost its grip on the everyday rituals and habits of ordinary people: "Rather than engage with what was happening, it started to mutter threats against the society of which it had been part, and to turn inwards."

It's an engaging book with lots of spicy gossip, and by no means everyone would agree with the authors' thesis. But clearly that sense of being under threat – us against the world, fighting in the cause of truth and righteousness – generates passionate loyalty, commitment and revenue. It fills churches with prayer warriors who truly believe they're on the right side in an End-Times battle against the forces of darkness. It creates ever-tighter groups of believers loyal to each other and to the gospel, whose churches grow by recruiting more and more people. And in doing so they become more and more detached from wider social currents, and more and more exclusive.

What's happening in the US among many conservative evangelicals fits this pattern exactly. And Christians need to acknowledge the dynamics of all this, and question it. Yes, there'll be points at which Christianity and culture are absolutely irreconcilable, and at which bad laws need to be fought to the last ditch. But there'll be others at which Christians need to be able to say, "The Church doesn't agree with this, but we don't run the country and we won't oppose it." Or, "We oppose this because we think it's bad for society, but if you decide to do it we'll be around to pick up the pieces." Or even: "Actually, you're right and we got this wrong."

What evangelicals should not do is hitch the gospel wagon to political causes and ideologies of whatever stripe. The Church that marries the spirit of this age will be a widow in the next, said Dean Inge. But churches that jump into bed with right-wing conservatism risk widowhood too.

Follow Mark Woods on Twitter: @RevMarkWoods