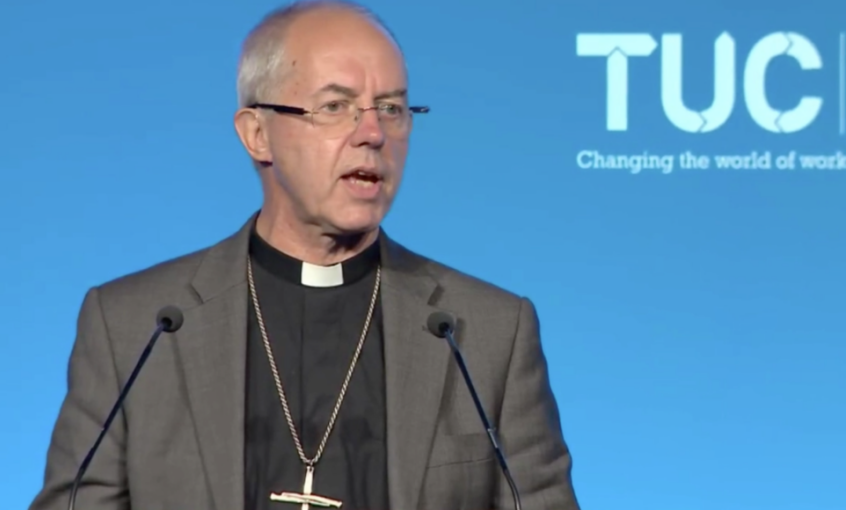

Ephesians tells us to put on the armour of God, and in September the Archbishop of Canterbury had to make full use of his as he faced a media backlash to comments he made about Amazon's policies on corporation tax and staff wages. The Spectator branded him a 'hypocrite', the Guardian called him an 'irrelevance' and suggested that he was an 'idiot that hadn't done his homework'.

I am full of admiration for Justin Welby. He put his head above the parapet and spoke out on behalf of the underprivileged in our society that bear their fair share of the tax burden. He was using Amazon as an example of a failing system that perpetuated inequality in our already unequal society. The day after his speech, the media – in all its forms, electronic, print, radio – reported on the archbishop's comments. Most were highly critical. However, he achieved what he set out to do; he made the issue current and relevant. I believe that in all likelihood, he was fully aware of the fact that the Church of England owned shares in Amazon and made his remarks in spite of this. Through this, he recognised that raising awareness of the inherent injustices of the UK tax and welfare system would far outweigh any criticism he may receive for his comments.

Two weeks after Justin Welby's speech, Amazon announced that 'it had listened to its critics' and increased its minimum wage in both the USA and UK. While we may not know what caused them to ultimately make this decision, I think the archbishop's comments certainly made them aware of the magnitude of this issue.

At the Central Finance Board, we look after the investible assets of the Methodist Church. With that role comes responsibility, and our priority is to both maximise our long-term investment returns while acting in accordance with our Christian principles. There are some 'sin' stocks that our ethics committee feels go beyond any acceptable tolerances for the Christian investor and we currently exclude about 14 per cent of the UK stock market on these grounds.

However, there are also many examples of companies whose management teams are focused on improving their ethical practices in otherwise grey areas. For example, on climate change, Shell and Total have shown some good progress by projecting what their emissions are on 'scope three' emissions – this relates to the emissions from using their products – eg if we were to go into one of their garages and fill up our cars, the emissions from the point we drive off.

We aim to encourage these improvements in behaviour. The extractives industry should be rewarded where it prioritises employee health and safety; power generators when they reduce their reliance on coal.

The question we must constantly be asking ourselves is whether we should give up on companies that are slow or resistant to change. As shareholders, we have a voice that is more powerful than that of the general public. We can file resolutions, table difficult questions at general meetings and vote. The faith community in the UK tends to vote together – our voice still commands respect in this country. We are stubborn and have thick skins. Just ask Justin Welby.

For me, divesting from a company is the last step in a prolonged assault upon company management. It is proof that we have failed. I would much rather accept criticism, both internally and externally, than concede defeat on some of the great challenges of our day. As Solomon said in Proverbs 29:25: 'It is dangerous to be concerned with what others think of you...'

Patience and faith are the key pillars of our faith and I believe they will also be the key drivers of change in the corporate world.

David Palmer is chief executive of the Central Finance Board of the Methodist Church.

The CFB and sister organisation Epworth Investment Management manage in excess of £1 billion for charities and pension funds. We are stewards of our investors' money and carefully select investments using Christian ethical criteria.