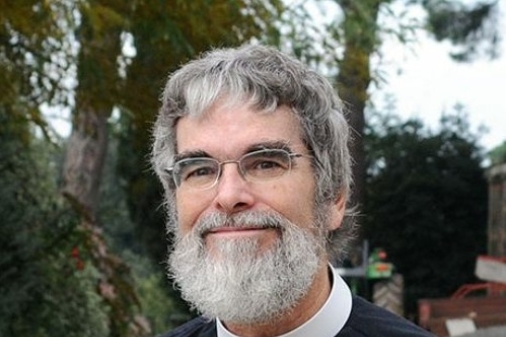

Leading American astronomer Dr Guy Consolmagno, director of the Vatican Observatory in Rome, is author of a new book, Finding God in the Universe.

Published in Darton, Longman and Todd's My Theology series, the book explores how astronomy can lead people to a deeper knowledge of the universe and its Creator.

Dr Consolmagno, who grew up in a Roman Catholic home in Detroit, joined the Jesuits in 1989 at the age of 37.

He has served as chair of the American Astronomical Society Division for Planetary Sciences. In 2014 he received the Society's Carl Sagan Medal for excellence in public communication in planetary sciences.

At the Vatican Observatory since 1993, his research explores connections between meteorites, asteroids and the evolution of small solar systems.

Christian Today spoke to Brother Guy about his book and how his faith in God inspires his work as an astronomer.

CT: In your book you write: "A fundamental truth about finding God in the universe is that if you already know God is present, then you can see God everywhere; but if you don't expect to find God, then you don't even think to look, and so God goes unseen. In order to find God, you have to have the faith to be able to look for God."

How did your training as an astronomer at the Massachusetts Institute of Technology (MIT) and the University of Arizona help you to own the faith in God that you were brought up with?

GC: First of all, I should emphasize that it was not the science itself that led me to God. The scientist in the office next to mine could see the same facts and come to a completely different conclusion — not only about God but even about what the data imply about our science!

Science, like faith, is a conversation; and conversations are more than just everyone agreeing with everyone else. That disagreement is what leads everyone involved in the conversation to see the truth more deeply.

But what did strengthen my faith during the years I was a student were the examples of the other scientists around me. One person I knew at MIT was deeply religious and even though it was a different religion from mine, his witness encouraged me to give witness to my faith.

He was also someone who was more interested in learning the truth than in glorifying his own reputation by having his own pet theories ratified. That led him to face learning new things with joy, not apprehension. He did all his science with a sense of fun.

On the faculty at Arizona I met two priests who were also astronomers, one of whom, George Coyne, eventually became my boss at the Vatican Observatory! But again, their example served as a witness of well-respected scientists who were not shy about living their faiths.

I would not be telling the whole story, however, without mentioning those whose example ran in the other direction. I was only just becoming an adult then, and I would look at scientists just a few years older than me as role models, examples of how adults might be expected to live, or as examples of what to avoid!

CT: You stress the importance of the Christian community in enabling people to have a properly informed faith in the God and Father of Jesus Christ. How has that been true in your experience?

GC: A big theme of my book is how in both science and faith we rely on a community to teach us what has been learned, to hear and help us understand what we are learning ourselves, and to give us a place to pass on those hard-earned lessons to the next generation.

There is nothing sadder to me than all those emails and letters, and sometimes even beautifully and expensively printed books I get that are filled with what the authors think is profound science, but which is in fact utter gibberish. The problem isn't that the authors are fools; often, quite the contrary.

The trouble is that they have not been a part of the great conversation on the topics that they are interested in. They don't really know what has already been learned, where the excitement of the new ideas can be found, or even what the words mean that we use when we talk with each other.

But that's true of life. You wouldn't choose a school, a career, a spouse, a new house, without talking it over with your family and friends, asking people who have gone before, giving advice to those following you, when they ask. And it's not just in big things; think of the how you'll chat to your family and friends every day about all the wonderful little things that happened at work, at school, around the house. That's what makes social media so popular.

That's why thinking you can "find Jesus on your own" is so false. You wouldn't even know Jesus was there to be found if you hadn't heard of Him from someone else. You don't have the time to reinvent the wheel, all of theology, by yourself. And you lose out on more than half the fun if you don't share what you've learned with a community of people who will know what you are talking about. That desire to share is why people write me those crazy letters and books, after all. But it's rude — and boring — to only talk and never listen.

CT: To what extent are the young Millennial scientists in their 20s and 30s whom you meet in your field more open to Christian faith than the baby-boomers of your generation?

GC: I certainly find the younger generation to be far more open to people with different religious faiths than in generations past. One of the good developments in our society is that we have learned that "diversity" is not only abstractly a good thing, but that it is in fact a source of joy and fun.

We love learning about new foods and new fashions, new kinds of music, new kinds of entertainment. We also get a better sense of who we are ourselves when we can contrast that with who we see other people being. In that sense, to be able to say that I have friends who are Christians, or Mormons, or Buddhists, makes me feel that my life is richer for it all.

The downside of course is that in such a view, your religion can become reduced to just another "lifestyle choice" like your preference for a particular brand of coffee or tea. Still, this situation is far better than the pressure to conformity that has led a lot of insecure scientists in the past - and we're all insecure! - to try to assimilate into what they thought the culture demands, to reject their religion in order to "fit in".

CT: The Apostle Paul affirmed in the New Testament that "since the creation of the world God's invisible qualities – his eternal power and divine nature – have been clearly seen, being understood from what has been made, so that people are without excuse" (Romans 1:20 – New International Version).

In your observation of the stars, how are God's eternal power and divine nature clearly evident in the way St Paul affirmed?

GC: Well, the first and most obvious is the fact that existence exists at all. This was expressed most famously by Leibnitz when he asked "why is there something instead of nothing?" It's important to remember that "nothing" is not just empty space, because even space and time are "something". Why does existence itself exist? But Paul is saying more than that. He is saying that we can see not merely God's existence, but the divine nature in the universe.

To me the part of science that shows this nature is in the laws that govern the universe. Certainly, the universe wouldn't function for very long without a set of logical laws, so there's no surprise that such laws exist and that they are logical. But what is really surprising - unnecessary but welcome - and a reflection of the divine nature, is that the laws themselves are so elegant, so beautiful. The stars are beautiful; so is the science that describes them.

Here's what I mean. There are lots of cars on the road, and they all get you to the same place; but some cars are far more beautifully made than others. Likewise, the machinery of the universe is beautiful. It's a Jaguar, not a Trabant.

In fact, when a scientist is trying to choose among possible theories to test in the lab, the first one to be tested — the one given the highest chance of being correct — is inevitably the one the scientist finds most elegant. Of course, elegance can be in the eye of the beholder, which is what makes science a job for human beings, not computers.

The next surprise is the joy and love that is experienced in this universe. I do science because I love to do it. I love discovery. I love the jolt of joy when I suddenly understand something that had been mysterious and at that time uncover new mysteries. I love that sense that, at that moment, I can feel God looking over my shoulder with delight as I learn and appreciate what He has done there.

I love how God can make such intricate and complex things out of such simple materials, such simple laws. Among those creations that I love are myself and my fellow human beings. This is a universe designed to make love possible.

And I love the fact that God has given us, mere creatures (see Psalm 8) the power to actually know and appreciate what we see around us and to be aware of how much more we still have to learn.

To me, this universe shows me a God who loves, who cares, who enjoys more than any cold machine, more than any remote Deist god, indeed more than any of the pagan goofballs who populated the old Roman and Greek mythologies.

Our God is indeed a God who is more than worthy of all the joy and praise and love we can give, and which we give in celebration of our merely being able to be a part of it all!