The Archbishop of Canterbury is being urged to apologise for tarnishing the reputation of a deceased bishop without sufficient evidence he was guilty.

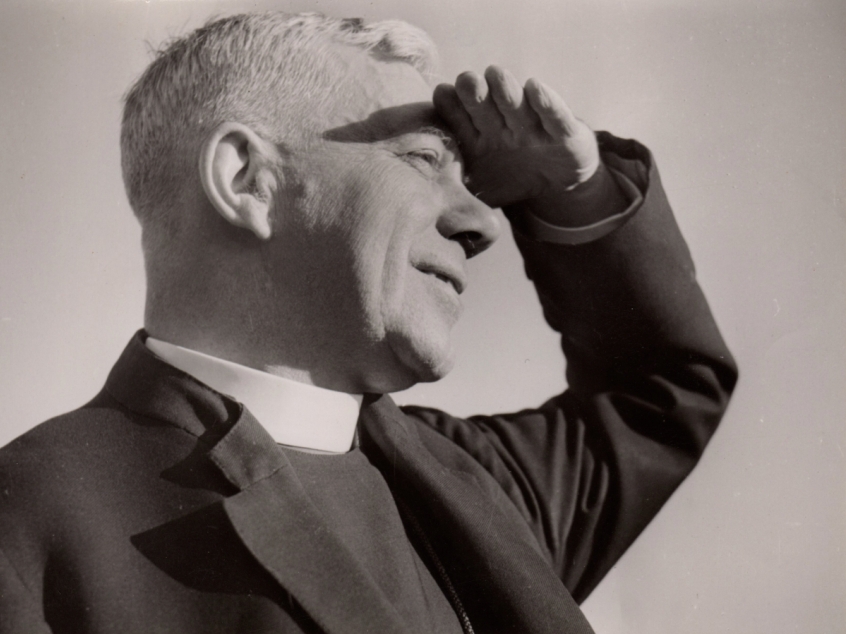

George Bell, the former Bishop of Chichester, was deeply revered in the Church of England and was one of the Church's most respected 20th century leaders. However his reputation was destroyed in 2015 when the Church of England appeared to admit he was a paedophile by publicly apologising to an alleged victim, known only as Carol, and paid her more than £30,000 in damages and legal fees.

A review chaired by Lord Carlile QC was launched into how the Church handled the case and a damning report published on Friday said 'serious errors were made' as a result of an 'oversteer' that presumed his guilt without fully looking at the evidence.

But Justin Welby refused to apologise to Bishop Bell's relatives in a statement that appeared to leave open the possibility of his guilt.

'The decision to publish his name was taken with immense reluctance, and all involved recognised the deep tragedy involved,' he said in a statement.

'We realise that a significant cloud is left over his name,' he added. 'No human being is entirely good or bad. Bishop Bell was in many ways a hero. He is also accused of great wickedness. Good acts do not diminish evil ones, nor do evil ones make it right to forget the good. Whatever is thought about the accusations, the whole person and whole life should be kept in mind.'

In a heated press conference at the CofE's headquarters in Westminster Welby, who was not present, was urged to apologise for the damage to Bishop Bell's reputation after Lord Carlile said he doubted the 'test for a prosecution would have been passed' under the evidence he had seen.

An experienced lawyer, Lord Carlile said: 'Had the prosecution been brought on the basis of that evidence, founded upon my experience and observations I judge the prospects of a successful prosecution as low. I would expected experienced criminal counsel to have advised accordingly.'

Asked what he thought of Welby's statement Lord Carlile said it was 'less than fully adroit'.

His report found that while the Church acted in 'good faith' its investigation was weak, did not find easily available evidence, and 'failed to follow a process that was fair and equitable to both sides'.

Bishops anxious to avoid being accused of tolerating or colluding in child abuse 'rushed' to apologise publicly without properly investigating the facts, the investigation said, and Lord Carlile pointed to an 'oversteer' where bishops assumed Carol was telling the truth without looking at the facts.

'As a result it was concluded all too easily that Carol was telling the truth and Bishop Bell was responsibly for serious abuse,' Lord Carlile told journalists.

'I regret that Bishop Bell's reputation, and the need for a rigorous factual analysis of the case against him, were swept up in a tide focused on settling Carol's civil claim and the perceived imperative of public transparency.'

The report appeared to indicate that Welby himself was behind the 'rush' to name Bishop Bell publicly.

While Welby, the lead Bishop on safeguarding Peter Hancock, and the current Bishop of Chichester Martin Warner all thanked Lord Carlile and said they would implement most of his recommendations, there remained a fundamental disagreement over whether Bishop Bell should have been named.

'The reputation of Bishop Bell was wrongly and unnecessarily damaged severely by public statements by the Church, which should not have been made,' said Lord Carlile. He said the Church should avoid 'illegitimate and unfair publicity against those whose liability for sexual abuse has not been proved'.

But Welby disagreed and said the Church is 'committed to transparency' and so would take a different approach. Bishop Hancock went further and said the Church 'would seek to avoid confidentiality clauses' in its settlements with claimants.

In response Lord Carlile said he 'regrets' their refusal and warned it runs 'the risk of creating transparent injustice'.

He said: 'The protection of innocence in my view is important, and I am disappointed that the Church has rejected that as a clear and general principle.'

This fundamental disagreement remains.

The question over whether transparency trumps the presumption of innocence until proven guilty is at the heart of this case. The Church, scorched by the accusations in Dame Moira Gibb's report that it colluded with the convicted abuser and disgraced former bishop Peter Ball, is clear it holds transparency of utmost importance.

In this case there will probably always now be doubts over whether Bishop Bell was guilty. For those convinced by Carol's testimony, Lord Carlile's judgment that there was insufficient evidence for a prosecution does not mean the abuse never happened, just that it was too long ago with too few facts to convince a jury. On the other hand, his supporters remain deeply angered by a stain on Bell's reputation they believe is wholly undeserved. Transparency in the case of proven guilt is one thing; it is another thing entirely in the case of unproven allegations, they say. The CofE does not agree, and Bell – whether deservedly or not – is a casualty.