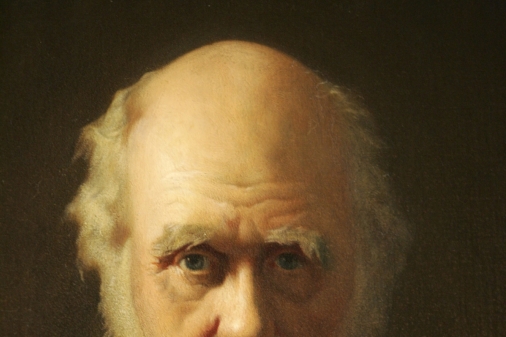

Today marks the anniversary of an iconic book's publication: Charles Darwin's On the Origin of Species, first released in 1859. The day has long been remembered (known to some as Evolution Day), and lamented by some religious believers. But is Darwin's culture-shifting theory still controversial?

Darwin's work is considered to be the foundational document for modern understandings of evolutionary biology – although scientific consensus has progressed and in some ways deviated from some of his ideas. At its heart it has come to represent the idea that humankind was not 'created' in its current form but as a species has evolved over a process of millennia, descending from apes and developing through natural selection.

It has been characterised as a cornerstone of secular, naturalistic materialism – since it supposedly pushed God and the Bible's account of creation out of the picture. It certainly did spark a new antagonism between science and religion, promoting a popular caricature between reasonable science and irrational faith. Was our world the work of an intelligent designer, or just the result of indifferent evolutionary processes?

It's worth noting that Darwin himself intended no such fight: he believed in God, and though he admitted his theology was 'a muddle' – his main struggle with Christianity was not about how humankind came to be, but the existence of pain today. Although his theory certainly challenged prevailing paradigms, and presents a puzzle for theologians trying to understand our origins – Darwin didn't see his work as a 'God-killer'.

But a century and a half later, what is to be made of On The Origin of Species? Among mainstream Christians today, evolutionary theory isn't that controversial. That is largely because, contrary to popular caricature, science isn't the enemy of faith. Darwin himself had an American friend, Asa Gray who believed evolution and Christianity to be perfectly compatible.

It's easy to imagine Christians just retooling their theology in the wake of Darwin to, for example, be a little more relaxed about interpreting the six-day Genesis account of creation. But thinkers as early as fourth-century theologian Augustine understood Scripture to be complex, and warned against taking literally what wasn't intended as such.

A more mature understanding of the relationship between biology and the Bible puts it thus: 'Science is about how things work, religion understands what they mean.' Christians have historically sought truth not just from the book of revelation (Scripture) but from the book of nature (the world around us, as mediated through scientific wisdom). In a world divinely made, all truth is God's truth – including the details about how exactly we got here.

That means it's not woolly liberalism to read the Bible's first chapters as they were intended: an ancient account detailing humanity's identity, purpose, and ultimate 'origin' – rooted not in blind forces but in a personal creator God. Modern groups like BioLogos make the case for 'an evolutionary understanding of God's creation', with key evangelical leaders like NT Wright, Francis Collins and John Ortberg standing behind them.

Pope Francis has also supported such an embrace, saying God is not 'a magician with a magic wand'.

Of course some still resist. Young Earth Creationists (YEC) passionately contradict evolution theory, insisting in an earth created between six and ten thousand years ago – with mankind not descended from apes but from Adam and Eve as Genesis says. One prominent YEC, Ken Ham, is clear that all we need to know about where we came from is in the Bible – those who say otherwise are opposing God.

As he put it: 'No scientist witnessed the origin of man, and evolutionary scientists only believe there were intermediate evolutionary links between an ape-like ancestor and man because they have disregarded God's Word and substituted their own fallible opinions in its place.'

But Ham's brand of creationism, though popular, is in the minority. One recent YouGov study found for example that amongst Brits and Canadians, most accept evolutionary theory. Meanwhile one in five UK atheists (and one in three in Canada) agreed that evolutionary processes couldn't explain human consciousness.

Perhaps that remains the only tension with evolution for religious believers, not that it's inherently wrong – but that it doesn't say enough. That it's one thing to say how we got here, but another to say why. That life is full of beauty, love, wonder - and must be about more than just a 'survival of the fittest'. On life's inherent meaning and origin in God, on its hope through God's grace and redemption - on these existential tenets Christians shouldn't be expected to shift.

Even Darwin, who ended his life an agnostic, couldn't deny some meaning behind reality. He wrote to Asa Gray: 'I cannot anyhow be contented to view this wonderful universe and especially the nature of man, and to conclude that everything is the result of brute force.'

He later described the 'impossibility of conceiving that this grand and wondrous universe, with our conscious selves, arose through chance'.

As it seems Darwin grasped, you could – and should – understand the facts of how humans came to be, but when it comes to 'origins' – evolution isn't all we need.

You can follow @JosephHartropp on Twitter