'Give me sweets': the sad reality of childhood poverty in Kenya's largest slum

English is one of many languages taught to children in Kenya. Just like when learning anything new, you tend to start with the basic necessities: 'hello', 'please' and 'thank you'.

But for the masses living in poverty, the rumbling call of a hungry tummy has to be answered, and sometimes the only way is by appealing to lighter-skinned visitors in their native tongue.

'Hello, hello!' – a band of voices come from behind me. I'm shocked to hear the use of English given the surroundings in an east African city. On the approach, children hold out their cupped hands, wide-eyed and hopeful, waiting on the westerners to provide, as they've had to learn through begging that they always do.

Out of small, parched mouths is uttered the only full phrase they can clearly remember – one that differs greatly from the usual 'How are you?' when greeting a stranger.

'Give me sweets.'

A few words that, if asked by a child at home, might have made me snap back with an index finger wagging furiously in their face, chastising them with a condescending 'Please?'.

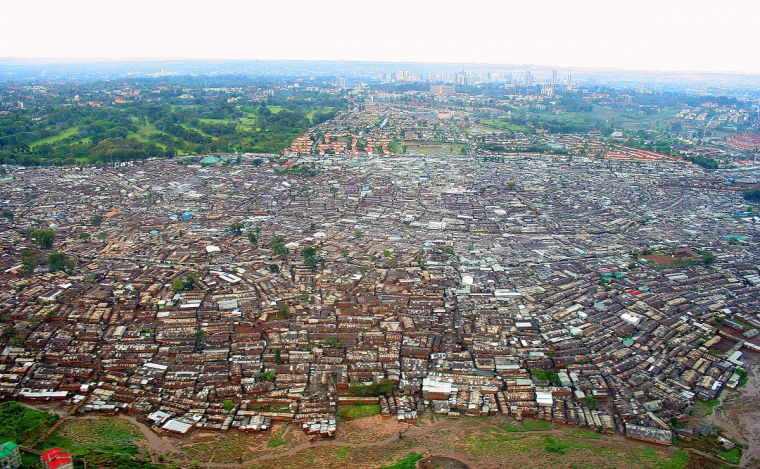

But when I heard the children singing this phrase on the streets of Kibera, Kenya's largest urban slum, I was too stunned to reply – or to reach into my pocket for the packet I knew I was hiding.

I studied their faces, some drawn with hunger, others splattered with the dust of the streets, and even some no more than a few years old loosely repeating the yearning mantra. And they stared back, perhaps confused at my stillness as if I wasn't understanding their clear demand, so they repeated it again and again in their plainest voice.

'Sweets, sweets.'

Fingers growing eager, some lightly gripped my arms while others stroked my palms as if to check that I was really there, waiting for me to provide – they had been told by their elders I surely would.

I obeyed their expectation and unwrapped the treats which had been melting in my tightly closed fist, placing the sticky presents into the hands of those who gathered around me.

Snatching was evident, as is the way with any children, and many clambered on top of one another to be first in line – I couldn't handle the brutality of it all, so I plainly said "all gone" before cowering away into the modern jungle.

I had been so taken aback in that moment and by the spectacle I was creating in the makeshift street I hadn't really processed what I'd done there, other than distribute my goods when asked to.

I only began to understand on reflection that what I was providing for these children was a moment of escape.

Kibera is noisy, bustling and foul smelling; it is unlike any childhood nightmare we could imagine, and easy for adults to pretend doesn't exist when you can easily escape it in your tour bus.

Houses are formed from tin and mud along pathways that wind along the banks of the 'river', or coagulated human waste, discarded plastic and rain water for those who looked closely enough.

It is an undeniably sad reality – with children having very little, some with no food or loving home to sleep in, others with nothing at all, and all with a limited understanding of childhood. So as much as it would be easy to walk past their begging, as many British people become accustomed to doing at home, it is not just for sustenance that children are forced to implore the 'muzungus' (white people).

These children crave a miniscule moment of childlike bliss, easily observed, given their lack of fussiness and a competitive desires to always be first in line. The sugar rush completely transforms the space around them, it brings colour and light – and who can blame a child for wanting a little piece of that? Who can blame them for leaving their manners at home?

One simple sweet, the object of so much desire and possibly the first known word of a foreign language, is the ultimate desire, over money, sustenance and ultimately freedom from poverty.

How bleak it is to remove sweets from the equation of childhood. Some might even argue that you are taking away happiness, or perhaps, as Willy Wonka thought, a world without 'pure imagination'.

The little ones have no understanding of what it means for me to have come from 'another world', living with a home, family and money – and they only concern themselves with a treat to take to the local school.

But they can imagine their own idea of another world in the buzz of a lollipop – and it gives them a taste of a 'normal' youth provided to the lucky few. The few who are sponsored by kind-hearted strangers that can afford to give out sweets to their heart's content – with the help of the hard-working people at Compassion.

And it was those same hard-working people who prepared me with sweets before I left for the streets, knowing the desires of the children they work with.

You might not be able to send sweets to Kenya, or take your own trip there to give them out, but Compassion is involved in the next best thing – sponsorship.

Sponsoring a child can help release them from poverty by providing education, food, and sanitation for a growing child, encouraging them to break out of the cycle, and it costs only £25 a month.

Best of all, writing letters to your sponsor child lets them know that someone cares and is willing to listen to their demands – it gives them the same feeling of childhood as a sweet, but the effect is lasting.

Giving out a sweet is one small step and a momentary break in the harsh reality of life in the slums.