Many people spend the majority of their waking hours sitting – at home, commuting and at work. Particularly when we're sitting for long periods at a desk, there are a few things we should keep in mind.

How should we sit?

Many people think there is one "good" posture. But actually, there isn't just one way of sitting. Different ways of sitting will place different physical stresses on our bodies, and variety is good.

To work out if a posture is "good" or not, we can assess it based on several things:

- the amount of muscle activity required to hold the position (too much muscle activity could be a problem as it can result in fatigue if held continuously for a long period)

- the estimated stress on joints, including the discs between the vertebral bones of the spine (too much physical loading stress could be a problem as it may cause pain in the joints and ligaments or muscles around them)

- whether the joints are in the middle of their range of movement or near the extreme (awkward, near end-of-range postures may put more stress on tissues around joints)

- the amount of fidgeting people do (moving about in your seat, or fidgeting, can be an early indicator of discomfort and may suggest a risk of later pain).

Given these criteria, research suggests there are three main options for how you can sit well at a desk. Each option has different pros and cons, and is suitable for different tasks.

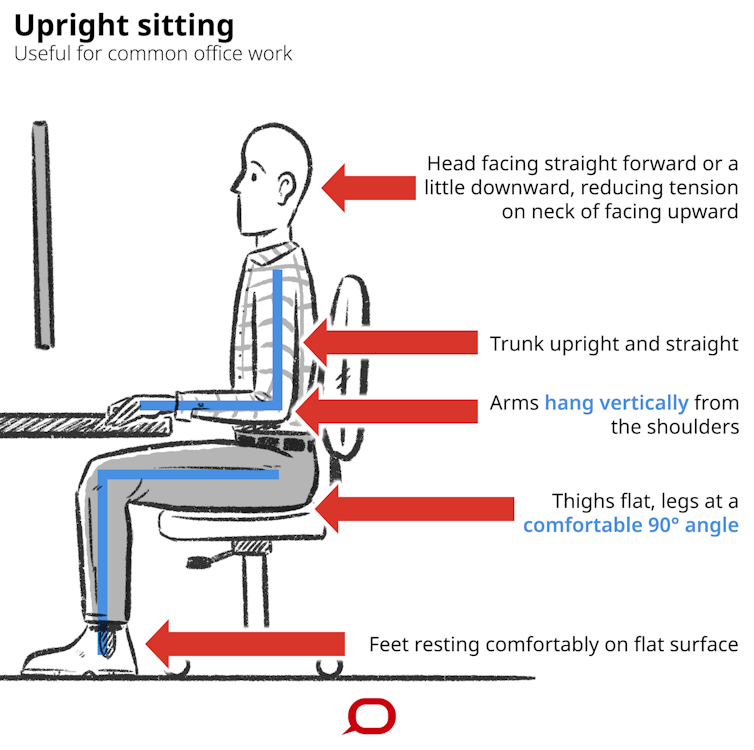

Option 1: upright sitting

This is probably the posture you think of as "good" posture. The defining feature of this option is that the trunk is upright.

A key component of upright sitting is that the feet can comfortably rest on a surface, whether the floor or a footstool. This position also makes it easy to adjust posture within the chair (fidget) and change posture to get out of the chair.

It's also important the arms hang down from the shoulders vertically with elbows by the trunk, unless the forearms are supported on the work surface. Holding unsupported arms forward requires the muscles connecting the shoulder and neck to work harder. This often results in muscle fatigue and discomfort.

The head should be looking straight ahead or a little downwards. Looking upwards would increase tension in the neck and likely lead to discomfort.

This posture is useful for common office tasks such as working on a desktop computer.

The Conversation, CC BY-ND

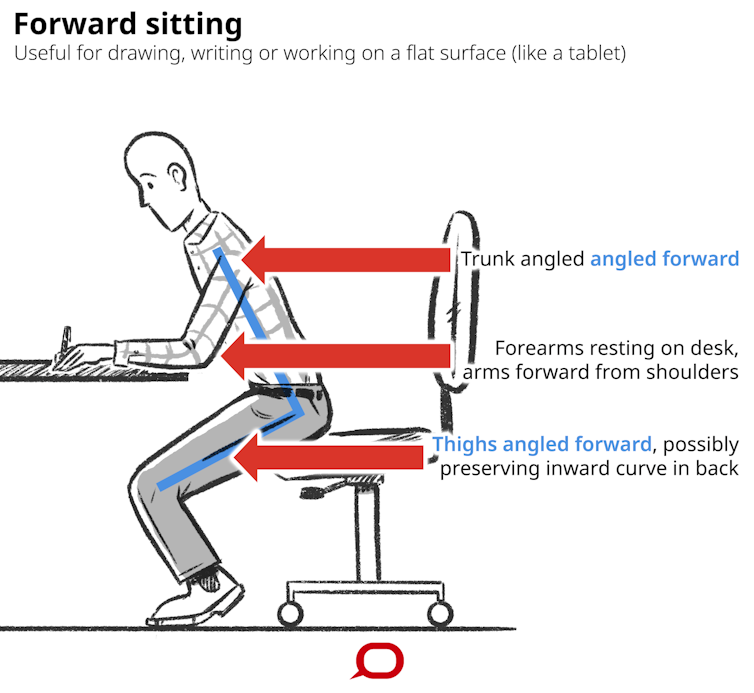

Option 2: forward sitting

The defining feature of this posture is that the trunk is angled forward, and the arms are rested on the work surface. Allowing the thigh to point down at an angle may make it easier to maintain an inward curve in your lower back, which is suggested to reduce low back stress.

For a time special chairs were developed to enable the thigh to be angled downwards, and usually had a feature to block the knees, stopping the person sliding off the angled seat base.

By perching on the front of an ordinary chair and resting your elbows on the work surface, you can use this posture to provide variety in sitting. This posture is useful for tasks such as drawing or handwriting on a flat work surface, either with paper or a touch screen device.

The Conversation, CC BY-ND

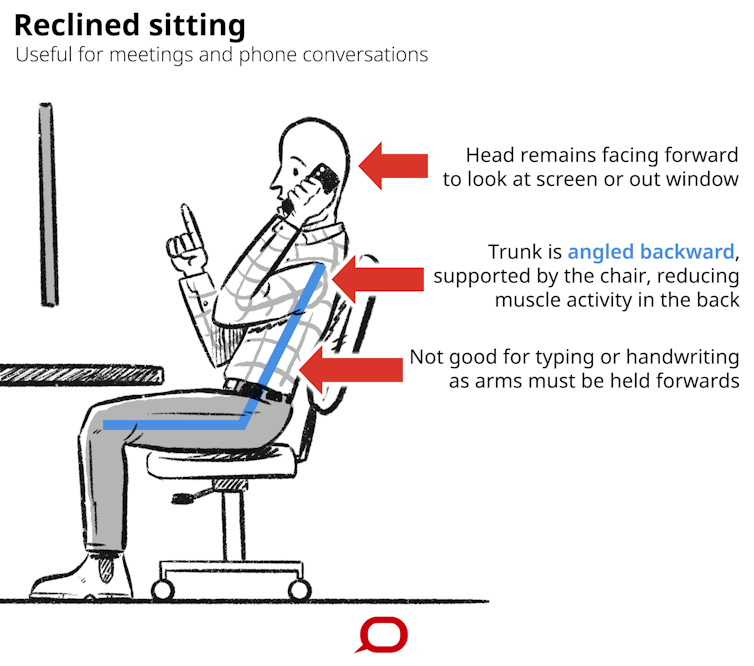

Option 3: reclined sitting

The defining feature of the third option is the trunk is angled backward, supported by the chair's backrest. Back muscle activity is lowest in this posture, as some of the upper body weight is taken by the chair.

This position may reduce the risk of fatigue in the back muscles and resultant discomfort. But sitting like this for hours each day may result in the back muscles being more vulnerable to fatigue in the future.

This posture is useful for meetings and phone conversations. But it doesn't work well for handwriting or using a computer as the arms need to be held forwards for these things, requiring neck and shoulder muscle activity likely to result in discomfort.

The Conversation, CC BY-ND

Final tips

- consider how much time you spend sitting each day, and if it's more that around seven hours, look for ways to reduce the total amount of time you spend sitting. For example, if you're an office worker you can stand instead of sit for some tasks (but don't stand for too long either)

- break up long periods of sitting with movement. Aim never to sit for longer than 30-60 minutes without allowing your body to experience alternative posture and movement, such as a short walk

- vary your sitting posture using the three options outlined above so your body has changes in the stresses placed on it

- remember there is no one good posture, but any posture held for a long period of time becomes a bad posture. Our bodies are meant to move regularly.

Leon Straker, Professor of Physiotherapy, Curtin University. This article is republished from The Conversation under a Creative Commons license.