How this Jerusalem tattoo parlour is continuing a pilgrimage tradition since 1300

The holy area that is Jerusalem's Old City may seem like an unlikely place to obtain a tattoo.

But in fact, at the thriving Razzouk Ink near the Jaffa Gate, the Razzouk family of tattoo artists are continuing a tradition of issuing ancient signs of Christian pilgrimage that has gone on since the Crusades.

Indeed, the tattoo parlour, which was founded in 1300, is 'carrying on one of the world's oldest tattoo traditions,' according to the Catholic News Agency.

The Christian tattoo tradition traces back to the Holy Land and Egypt as early as the 6th or 7th Century, spreading throughout Eastern Christian communities such as the Ethiopian, Armenian, Syriac and Maronite Churches.

Even today, many Coptic Churches require a tattoo of a cross or other proof of Christian faith to enter a church.

Other tattoo traditions among groups such as Celtic and Croatian Catholics emerged separately and at a later date.

But with the advent of the Crusades beginning in 1095, the existing practice of tattooing pilgrims to the Holy Land expanded to the European visitors, with numerous accounts dating back to the 1600s describing Christians receiving a mark of their pilgrimage on its completion.

Wassim Razzouk, 43, told CNA: 'We are Copts, we come from Egypt, and in Egypt there is a tradition of tattooing Christians, and my great, great ancestors were some of those tattooing the Christian Copts.'

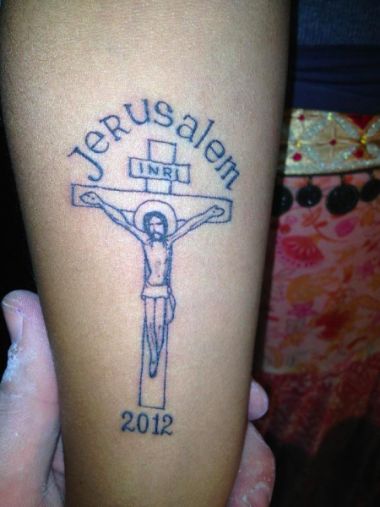

Speaking to Christian Today by telephone today, Wassim added: 'This is a traditional practice which has originated from the medieval times or even earlier than that and coming to the Holy Land at that time was a once in a lifetime event – not as simple as today, going online and ordering a ticket – so to commemorate that once in a lifetime event the pilgrim wanted something as proof – like a certificate of pilgrimage. This was the ultimate voyage in life, to come to the Holy Land, and getting this tattoo was the ultimate certification of pilgrimage – like a stamp, and this tradition has carried on until now, and it never changes, despite the ease of coming to the Holy Land now. It's like a sign of pride and honour.'

CNA witnessed the Razzouk family help a Catholic bishop from Europe plan a tattoo he hopes to receive once he completes a personal pilgrimage later this year. Weeks earlier, Theophilos, the Coptic Bishop of the Red Sea, came to the Razzouk Family receive a pilgrimage tattoo. Other patrons have included Christian leaders of Ethiopia, persecuted Christians, and Christian pilgrims of all denominations from around the world.

The Razzouk family themselves have their roots in Jerusalem as pilgrims. After many pilgrimages of their own, the Razzouk family relocated permanently to the Holy City around 1750.

'A lot of them decided to come to the Holy Land as pilgrims themselves and decided to stay,' Wassim said. 'For the past 500 years, we've been tattooing pilgrims in the Holy Land, and it's been passed down from father to son.'

Wassim explained to Christian Today that while Catholics tended to choose the Jerusalem Cross as their stamp, eastern and Orthodox Christians went for crosses from their traditions.

The CNA reported that during its visit to the shop, two women from western Armenia – lands now controlled by eastern Turkey – came in and explained that they had just completed their pilgrimage to the Holy Land and wanted to get a traditional pilgrim's tattoo with no alterations. They both picked a stamp of the traditional Armenian Cross, a crucifix that incorporates delicate floral design elements.

'Business is good,' Wassim told Christian Today.

But according to the CNA, traditions of Christian tattooing in Jerusalem have come close to extinction on several occasions: In the 1947 War for Israeli Independence, many of the Palestinians who practised tattooing fled from Jerusalem for their safety, including the Razzouk family. After that war, the Razzouk family returned, but they were nearly alone in doing so: few other Christian tattoo artists decided to return, leaving Razzouk Ink as the last ancient Christian tattoo parlour.

A little over a decade agom the family tradition seemed in doubt when Wassim and his siblings decided to pursue other professions.

'I didn't really want to do this,' Wassim told CNA. 'I wasn't into tattooing and since this was sort of a responsibility, I didn't want to do it.'

But, Wassim said: 'One day I was reading something online, an old article where my father was being interviewed. He was saying he was really sad: he thought this tradition and this heritage of our family was going to end because I didn't want to do it...I didn't want to be that guy whose name was written somewhere in history as the guy who discontinued this – the guy who killed it.'