How did Judas die?

That's easy. Matthew 27: 3-8 says: "When Judas, who had betrayed him, saw that Jesus was condemned, he was seized with remorse and returned the thirty pieces of silver to the chief priests and the elders. 'I have sinned,' he said, 'for I have betrayed innocent blood.'

"'What is that to us?' they replied. 'That's your responsibility.'

"So Judas threw the money into the temple and left. Then he went away and hanged himself" (NIV).

The priests then used the money to buy a field as a foreigners' cemetery, which became known as the Field of Blood.

How did Judas die?

That's easy. Acts 1: 18 says: "With the payment he received for his wickedness, Judas bought a field; there he fell headlong, his body burst open and all his intestines spilled out" (NIV). The place became known as "Akeldama", Field of Blood.

Now, aren't these completely different accounts of the same event, which cannot both be true?

No, some people insist. You see, what happened was that Judas hanged himself on a tree – as told by Matthew – at the top of a cliff. The rope broke and he fell all the way to the bottom. When he landed, he suffered the injuries described in Acts 1. So they're both true, and there's no problem.

The trouble is that this version of Judas' death is really, really hard to believe.

Of course, there are other parts of the Bible which a non-believer would find tough to swallow. Every single one of the miracle stories, for example.

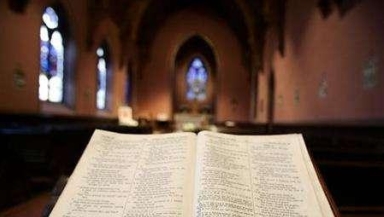

But for the traditional evangelical believer, who wants to hold to the authority of scripture, it's essential to hold that what the Bible says is true. So it can't contradict itself, and if it appears to contradict itself there must be a way to reconcile different accounts.

I think we need to be more honest than that. It's true that logically, there's nothing impossible about this way of reconciling two stories. But I think we need to admit that that's not where the evidence leads us.

I think trying to reconcile those different stories of Judas' death by creating a fiction that manages to account for the hanging and the internal disruption is just wrong, and it's dishonouring to God.

It's far, far more likely, to the extent of being blindingly obvious, that two different stories have descended to two different writers. Both are recorded. The chances are that one of them got it right, and the other didn't. Both have things to tell us, one of them about repentance and remorse and the other about divine retribution. But they can't be reconciled through the sort of mental gymnastics needed if we're to believe them both at once.

If we were reading any other history, we'd say that they just don't fit. But many Christians insist that the Bible has to be judged by different rules.

This is because, as 2 Timothy 3:16 says: "All Scripture is God-breathed and is useful for teaching, rebuking, correcting and training in righteousness." For many Christians, this means that every word of the Bible is true, and has to be accepted uncritically. It's God's book, and doubting any of it means doubting God.

In its extreme form, this is the "dictation theory" of inspiration: that the biblical writers were only passive transmitters of revelation, nothing more than human recording devices.

Most conservative evangelicals would say that they didn't believe that. However, the standard alternative – plenary verbal inspiration – comes pretty close to it. Defined by a conference of nearly 300 evangelical biblical scholars in 1978 through the 'Chicago Statement on Biblical Inerrancy', the doctrine of the verbal inspiration of scripture asserts the truth of every word of the Bible as originally given (the statement acknowledges that original manuscriptures have been lost, but says that the available manuscripts are very accurate). In one of a series of statements saying what the scholars affirm and deny, it says: "WE AFFIRM that inspiration, though not conferring omniscience, guaranteed true and trustworthy utterance on all matters of which the Biblical authors were moved to speak and write.

"WE DENY that the finitude or fallenness of these writers, by necessity or otherwise, introduced distortion or falsehood into God's Word."

It also says: " WE AFFIRM the unity and internal consistency of Scripture.

"WE DENY that alleged errors and discrepancies that have not yet been resolved vitiate the truth claims of the Bible."

I understand the strength of this appeal. I grew up in a church that taught it with passion. If you didn't believe that every word of the Bible meant exactly what it said – with due allowances made for metaphor, poetic language etc – then you didn't believe the Bible. And if you don't believe the Bible, what's left? Why should you believe that it's wrong to commit adultery, or that Jesus was God, or even that he ever existed? It's all or nothing: holding to this view of inspiration is the real theological red meat.

The trouble is that this theory of inspiration is just that – a theory. The Bible nowhere explains exactly what's meant by inspiration. Instead, it talks about what it does: "For the word of God is alive and active. Sharper than any double-edged sword, it penetrates even to dividing soul and spirit, joints and marrow; it judges the thoughts and attitudes of the heart" (Hebrews 4:12).

The verbal inspiration theory was framed by people who had a high view of scripture and wanted to rescue it from the attacks of liberal theologians who didn't take inspiration seriously at all. The trouble is that they claimed too much. So, another clause in the Chicago Statement says: "WE AFFIRM that Scripture in its entirety is inerrant, being free from all falsehood, fraud, or deceit.

"WE DENY that Biblical infallibility and inerrancy are limited to spiritual, religious, or redemptive themes, exclusive of assertions in the fields of history and science. We further deny that scientific hypotheses about earth history may properly be used to overturn the teaching of Scripture on creation and the flood."

So the verbal inspiration of scripture also commits you to young-earth creationism and a literal, world-wide flood. Even the idea that the world is millions of years old is a hypothesis, no more.

Is there a way of believing the Bible to be inspired by God, the infallible witness to Jesus Christ, the controlling, normative record of God's dealings with human beings through the ages, which doesn't require us to do violence to history, science and reason?

Maybe we should start from here.

The Bible as we have it is what God wanted us to have. Through all the vagaries of history, as the inspired writers spoke into their different contexts, as the early Church was deciding which books it should regard as scripture and which weren't, through the copying and recopying of ancient manuscripts, God was bringing into being a book that was utterly precious and unique. Everything in it is there because God wants it there.

I don't believe for one moment that the Bible is compromised by honesty about the parts where it contradicts itself or where the biblical writers, speaking spiritual truth in the context of erroneous ideas about science and nature, simply got things wrong.

I do believe that Christians are compromised when they try to make the Bible say things it never said, because it fits a particular theory. We don't need to do it. The Bible is bigger than that, and it can speak for itself: our job is to learn to understand it.

Follow @RevMarkWoods on Twitter.