How sacred music enchants the secular world

If you're wondering what the fuss is about or whether it's worth the bother to get out and hear some sacred music over the holidays, track down a video that went viral last week of actors Jamie Lee Curtis and Colin Farrell listening to a piece of choral music that illustrates how emotional and spiritual sacred music is — no matter what you believe.

Curtis and Farrell were discussing their latest films, and Farrell, who had spent time in his native Ireland working on "The Banshees of Inisherin," explained that when he is working on a role, he finds "a piece of music that stirs me. And then I listen to that for the film."

Curtis said to Farrell, "Tell me a piece of music for this movie."

Farrell took his phone out and placed it on the table between them. The music, which played for about 30 seconds, was dramatic and haunting. A canopy of Italian voices floated above string instruments.

But the real magic was the nonverbal interaction between Curtis and Farrell as they experienced and contemplated the beauty of the piece. Curtis was visibly moved, first by the music but more deeply by watching Farrell's delight in listening to the piece.

By the time Farrell said, "It's nice, isn't it?" Curtis was choked up.

"It's beautiful. It's an accident it's an Irish composer. Patrick Cassidy is his name," Farrell added.

Curtis interjected, "It's not an accident."

On watching the interview — and it must be watched, as no description can remotely capture the depth of emotion and connection — I was struck by Curtis' belief that something other than chance led the music of an Irish American composer to move in Farrell's Irish heart.

But the sense of the divine was not injected only by Curtis' dismissal of coincidence. God's glory was present in the music itself.

The piece, "Vide Cor Meum (See My Heart)," was the product of an early collaboration between Cassidy and Oscar-winning film composer Hans Zimmer ("The Lion King," "Dune"). It scores an opera scene in the 2001 horror procedural "Hannibal," a sequel to 1991's "The Silence of the Lambs."

Anyone who has seen the film will recall the dramatic cinematic power of the opera scene in Florence. A local detective has recently discovered the identity of escaped American serial killer Hannibal Lecter. He takes his stunning and much younger wife to the opera, which Lecter also attends. Afterward, Lecter presents the wife with a copy of the libretto.

The music stands alone as sublime, as Farrell relayed to Curtis. Its ethereal beauty is sufficient to complement and elevate the climactic moment in the plot.

But there's something about choral and orchestral music that almost inherently orients the listener toward lovelier, higher and more ultimate things.

As Farrell tells Curtis after they finish listening: "There's forgiveness, there's revelation, there's hope, there's the acceptance of sadness, not just the presence of sadness, not the acknowledgment of it, the witnessing of it, but the accepting of it as a part of our life."

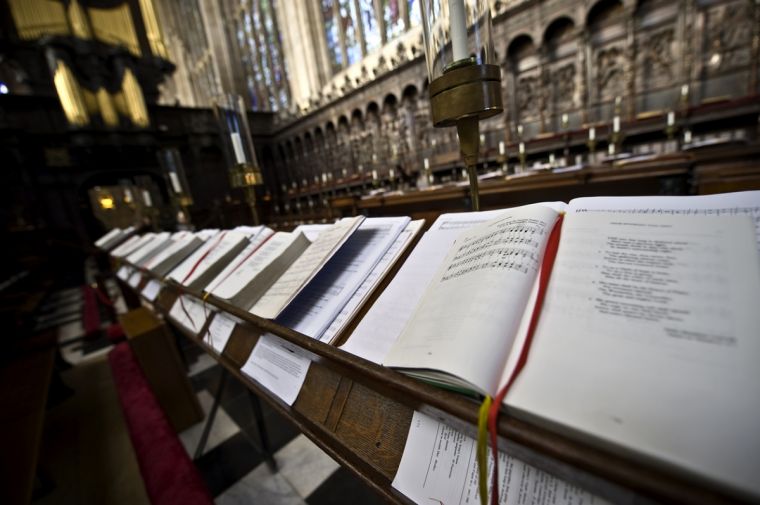

This is why sacred choral music has stood for centuries as the aesthetic height of Christian worship and devotion, as all manner of fads and replacements have faltered and ultimately revealed their relative inferiority.

It is no mistake that oratorio works, like Handel's "Messiah," often performed at Christmas though an Easter composition, remain among the most well-known and best-loved musical works in the world. Within and beyond Christendom, millions mark Advent with choruses like "O Thou that Tellest Good Tidings to Zion" and "For Unto Us a Child Is Born."

And in a post-Christian society, movies that depict sacred choral music carry a great deal of cultural power. Few in the millennial generation — or their Baby Boomer parents — will ever forget the scene in "Home Alone" when Kevin walks into a church and hears a children's choir sing a gorgeous John Williams arrangement of the ineffable Christmas hymn, "O Holy Night."

Yet even when the explicit religious content of choral music is not immediately apparent, its spiritual power is often evident. Such was the case with the Cassidy aria in "Hannibal." The movie's director, Ridley Scott, remarked in comments about the making of the film, that music "is the final adjustment to the screenplay, being able to also adjust the performance of the actors in fact."

A casual moviegoer will understand from Lecter's apparent flirtation with the police inspector's wife that the aria is about a man's longing for a woman (though Lecter is more curious about FBI agent Clarice Starling, who has studied and pursued the serial killer).

But there is much more at play in the composition, which is based on a Dante text from the late 13th century, "La Vita Nuova." It is an ambitious work of emotional autobiography in which Dante muses on both courtly and divine love, expressing how the experience of human love may point to unity with God.

Cassidy's aria includes sung dialogue between Dante's voice in Italian and the voice of God in Latin. It is a profoundly religious text, then, giving a sublime and dreamlike reflection on the heart of God and the heart of man.

It is thus wholly unsurprising that a piece of music that Colin Farrell listened to on repeat for months and moved Jamie Lee Curtis to tears is not only musically exquisite, but also theologically robust.

We may notice it more at Christmastime or at the movies, but sacred choral music has the power to move all of us, religious or secular, just about any time. Its staying power is not only its beauty, but the truths it conveys.

With a bit of attention and appreciation, no matter how far from God we have wandered, we can hear sacred choral music as an invitation: "Vide Cor Meum."

See My heart.

© Religion News Service