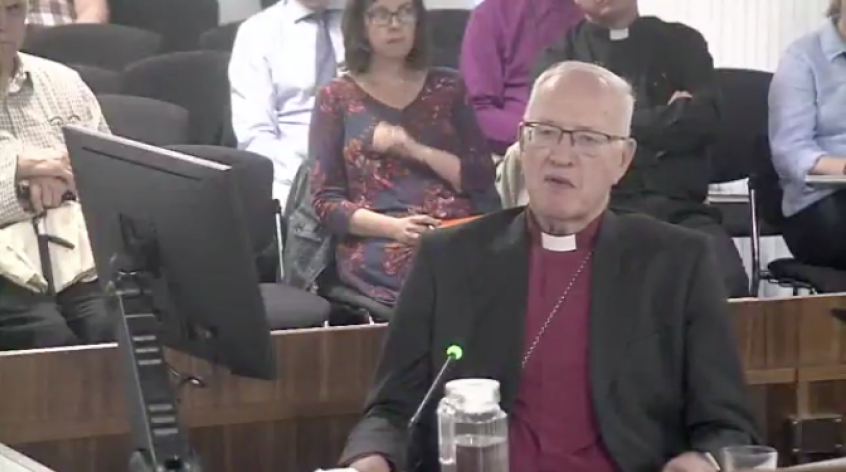

Lord Carey's testimony to the Independent Inquiry into Child Sexual Abuse (IICSA) yesterday made for depressing listening. The transcript is here.

The focus of this week's hearings is on Peter Ball, the former bishop of Gloucester who was found guilty in 2015 of misconduct in public office and indecent assault after he admitted abusing 18 young men from 1977 to 1992. He was sentenced to 32 months in prison and released in February 2017.

What makes Ball a fit subject for IICSA is that so many people knew about his behaviour without being prepared to confront it. What emerged from yesterday's hearing confirmed previous findings. Ball was a good egg, one of us, a charismatic, able clergyman with an influential ministry. Carey found it almost impossible to believe he would behave so badly. Even after his arrest, he wrote to him in terms he admitted were 'sickly', saying: 'Peter, I want you to know you are in my heart and constantly in my prayers. You need to know further that the matter does not diminish my admiration for you or my determination to keep you on the episcopal bench. You are greatly loved by so many in the church...so be encouraged and don't lose heart.'

He wrote to churches in Ball's Gloucester diocese saying: 'We hope and pray that investigations will clear his name and he will be restored to his great work of Christian ministry.' He wrote on his behalf to the chief constable of Gloucestershire Police, Albert Pacey, and supported the Church's provision of funds for his legal defence.

It's fair to say Carey shows contrition, though it's noticeable how much he uses 'we' rather than 'I'. The abused, he said, were 'let down by me and others in the church'. 'They fell into the trap of a pretty wicked person, a deluded person, who used his considerable influence to shape them wrongly. I regret we didn't see that earlier and I want to say we failed the abused in a number of different ways.'

However, a repeated theme of his testimony is that it all happened 25 years ago, and things were different then. People weren't as aware of the dangers someone like Ball posed, or of the effect sexual abuse can have; at one point Carey said that because the abuse was not 'penetrative', 'we didn't think it was all that important' – though he adds, 'I think we were wrong about that.'

He took issue with the current archbishop of Canterbury, Justin Welby, who wrote to him after the publication of the Gibb report into the Peter Ball case asking him to step down from his role as a bishop. Welby had told him that as a newly ordained minister at the time, he himself was well aware of safeguarding procedures. Carey said that these were not 'right at the front of our mind' in those days. He has previously described Welby's treatment of him as 'shocking' and 'quite unjust'.

What, then, do we learn from the former archbishop's testimony? Arguably not much. Carey's point that things were different 25 years ago is entirely valid. He should not be made a scapegoat for institutional failings, a culture of deference or widespread ignorance about the prevalence of sexual abuse. But at the same time, his personal failure to comprehend the effects of Ball's offences, his repeated willingness to give him the benefit of the doubt and his continued 'pastoral' sympathy for him are simply baffling.

The Peter Ball case shows why the present safeguarding infrastructure is so necessary for the church and for wider society. Most people are trustworthy; some aren't, and they can do so much damage that a culture of wariness is fully justified.

What is noticeable about the Ball case is how little attention was paid to his victims. It's in this area that the Church still has a great deal of work to do. By the end of the IICSA inquiry, the scale of this work might be clearer. If nothing else, no one can ever again assume that rank, charisma or reputation should be a guarantee that someone isn't also deeply wicked.

The hearings continue.