In European countries where there is a church tax, most people are happy to pay it, even if they hardly attend services, new research has found.

Austria, Denmark, Finland, Germany, Sweden and Switzerland are among the countries in Europe that continue to tax registered members of religious institutions.

In many countries, the church tax is mandatory for all members unless they opt out by deregistering from their church.

Research by Pew has found that although some Europeans are opting out, "there does not appear to be a mass exodus" and many continue to pay the tax out of a conviction that religious institutions contribute to the common good.

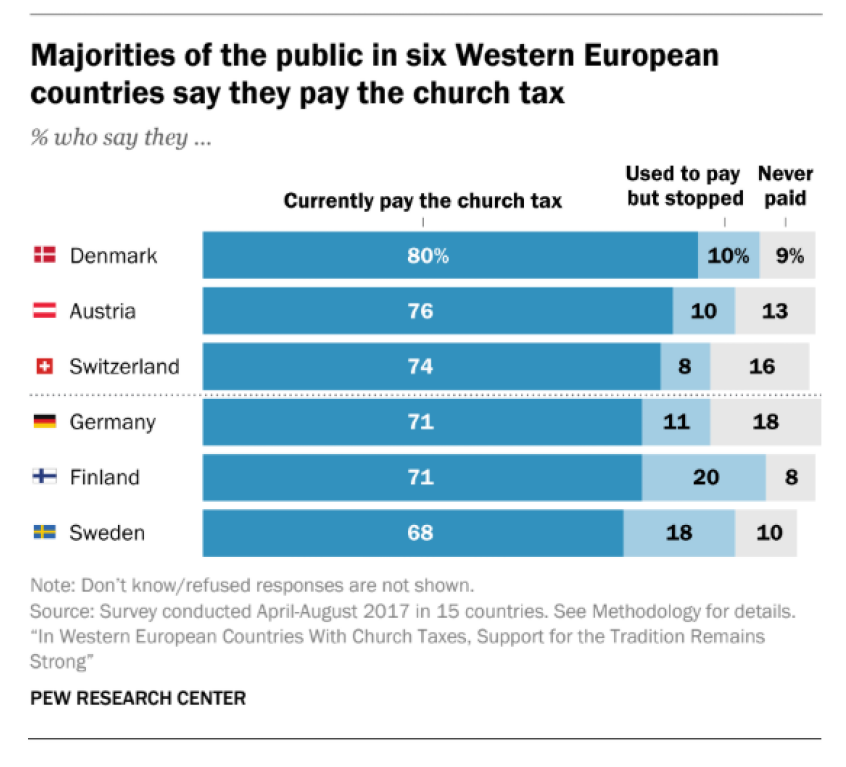

A majority of the population continue to pay the church tax in Austria, Denmark, Finland, Germany, Sweden and Switzerland. This ranged from 68 per cent of survey respondents in Sweden to 80 per cent in Denmark.

Finland had the highest proportion of people leaving the church tax scheme (20 per cent), but in all six countries, the proportion who had stopped paying was below one fifth of the population.

"Giving a share of one's income to the church has been a part of European tradition for centuries," Pew said.

"Today, several countries continue to collect a "church tax" on behalf of officially recognized religious organisations, in some cases levying the tax on all registered members.

"These payments add up to billions of euros annually and represent the biggest source of revenue for many religious institutions.

"But in some countries, growing numbers of people have been opting out of the tax by formally deregistering from their churches, perhaps another symptom of secularisation in the region."

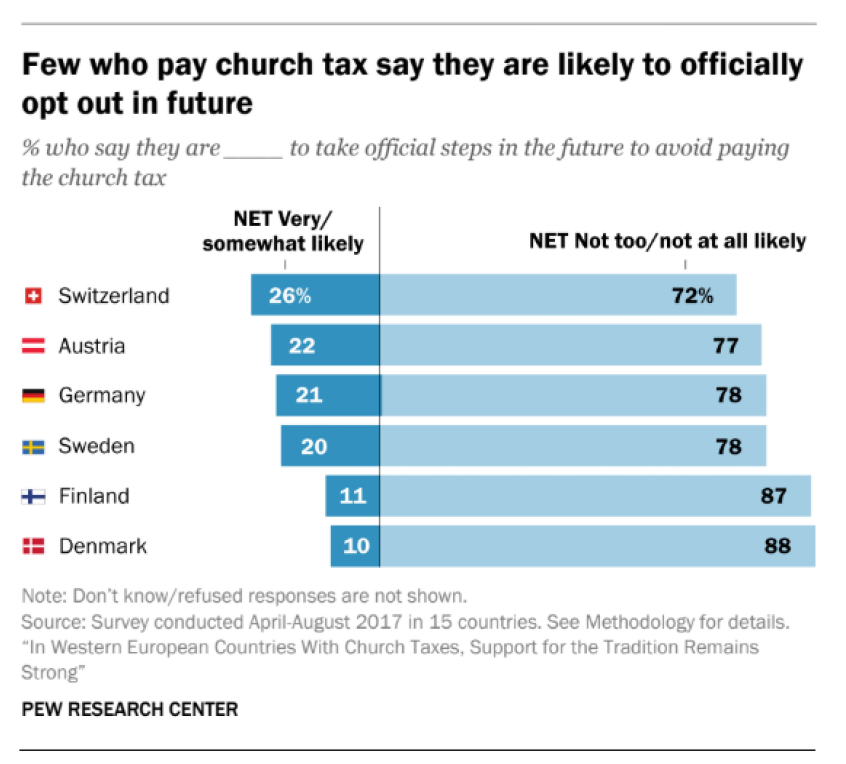

Among those who said they pay the church tax, there was little sign that they would opt out any time soon. Large majorities told Pew research that they were "not too" or "not at all" likely to deregister from their churches in order to avoid paying the tax in the near future. This included nearly nine-in-ten people in Denmark and Finland.

Not surprisingly, the study found a correlation between religious identity and the likelihood of paying the church tax. In Austria, 95 per cent of those who pay the church tax describe themselves as Christians. In Switzerland, the figure was 94 per cent.

This is despite many people who describe themselves as Christians in Western Europe saying they only attend church a few times a year.

Most of those who did not pay the church tax said they were religiously unaffiliated but in some places significant proportions were still paying it. A fifth of the church tax payers in Denmark (22 per cent) and a third in Sweden (32 per cent) described themselves as having no religious affiliation.

Pew said some people may continue to pay the church tax despite not being religious because they are either unaware that they can opt out or because doing so would require too much effort.

"In countries with a mandatory church tax, people generally enter a church's rolls at baptism – overwhelming majorities of Western European adults say they were baptized – and they must officially deregister from their denomination to avoid the fee," it said.

"Not only is this a dramatic step for some, but it also requires knowledge that the option exists and how to exercise it, such as how to obtain and file the necessary forms.

"Staying on their church's tax roster is the default status for people who are not sufficiently motivated to opt out."

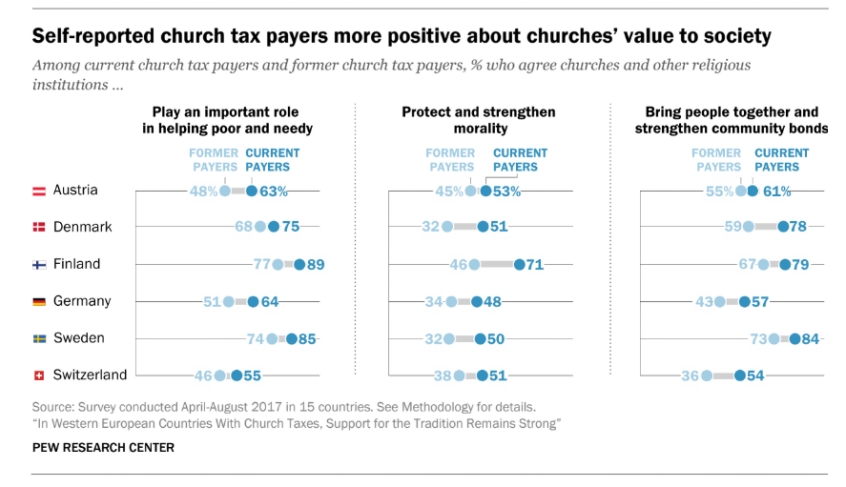

The study also found a link between people paying the church tax and having a positive view about the role of the church in society, with many of those who pay it saying that religious institutions strengthen morality, bring people together and help the poor. They were also less likely to believe in a separation between religion and government policies.