Irreplaceable: The Quaker meeting house that speaks of quiet faith

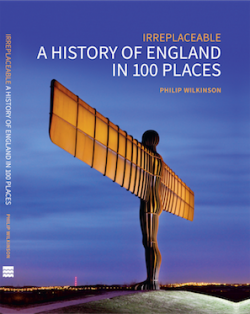

'Irreplaceable: A History of England in 100 Places' illustrates 100 historic places, guided by public nominations and a panel of expert judges, including Robert Winston, Mary Beard, Will Gompertz and Baroness Tanni Grey Thompson. Historic England designed the campaign with the support of specialist insurer Ecclesiastical to celebrate England's remarkable places.

Among the religious buildings selected by the Dean of St Paul's, Dr David Ison, is the Quaker Meeting House at Farfield, West Yorkshire. This extract is used with permission.

The Religious Society of Friends, known popularly as the Quakers, began in the mid-17th century in Lancashire. They believed that God spoke directly to people through Christ, so they had no priests, liturgy or sacraments; other key beliefs and practices included opposing warfare and refusing to swear oaths.

These beliefs set them apart from the Church of England, and meant that they (along with groups such as Presbyterians, Independents and Baptists) were categorised as nonconformists. These groups were frequently persecuted until in 1689 the Act of Toleration allowed them to worship freely, under certain conditions.

From 1689, Quakers began to build their own meeting houses, where they could worship in their own way. One of the very first was the Farfield Meeting House near Addingham in West Yorkshire. There had been Quakers in the area since the 1650s, when Anthony Myers, of Farfield Hall, met a group of Quakers and allowed them to worship at his home. In 1666 he gave them a 5,000-year lease on a plot of land where they could bury their dead, and in 1689 they built a meeting house adjoining the burial ground.

Like most early meeting houses, the one at Farfield is very simple architecturally – the Quakers in general shunned ostentation and, like other nonconformists, eschewed statues or other images in their places of worship. The meeting house is a rectangular building of rubble masonry with stone mullioned windows. Its grey stone walls and simple architecture fit perfectly into the the surroundings – it could almost be a small cottage.

Nearby are five table tombs of members of the Myers family. Although plain, these tombs are unusually large and ostentatious for Quaker graves – large tombs were more common among early Quakers, but many of these were removed after 1717, when the Quakers' Yearly Meeting condemned such memorials as a 'vain custom'. Most Quakers had very small stones or unmarked graves. The meeting house interior is also very simple, with plain white walls, wooden benches to sit on, and a raised dais or stand at one end where the group's elders sat.

Farfield Meeting House is an early example, but soon Quaker meeting houses were being built all over England, and members of the Society of Friends were increasingly respected for their integrity. Because nonconformists were not allowed to attend university, many Quakers went into business. Some of the country's most successful businesses, such as Fry's and Rowntree's, were run by Quakers, and members of these families also championed social reform and had a beneficial influence on wider society. These developments had their roots in the early Quaker communities based at meeting houses such as Farfield.

This meeting house remained in use by the Quakers until the 1890s. Subsequent uses included conversion to an artist's studio, which involved little alteration to the building.

In 1994 the meeting house was transferred to the care of the Historic Chapels Trust, which repaired it and now looks after it. The Farfield Meeting House is preserved as one of the earliest purpose-built places of Quaker

worship, and as a symbol of the importance of religious nonconformity in the history and culture of England in the 17th and subsequent centuries.

'Irreplaceable: A History of England in 100 Places' is published on September 18 by Historic England, price £20.