The end is nigh at Armageddon – at least for an old Israeli prison near the ancient ruins of Megiddo, by tradition the site of the apocalyptic biblical battle between good and evil.

Half an hour's drive south of Nazareth, Armageddon is a popular site for the coach loads of tourists visiting the sites of the Holy Land. There is also a busy programme of excavations.

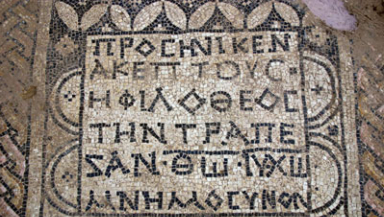

In 2005, work to expand the aging Megiddo Prison uncovered the remains of a 3rd century Christian prayer hall, including a mosaic referring to 'God Jesus Christ'.

The building with the mosaic was excavated, earlier artefacts found, and the site was covered up under the supervision of archaeologists.

Now, after years of legal and bureaucratic delays, the prison is to be relocated, freeing up the site for further exploration potentially as early as 2021.

The prospect already has archaeologists excitedly talking about an area they have started to call 'Greater Megiddo'.

'When the Christian prayer hall was first found beneath the prison, we were all excited for one minute,' said Matthew Adams, director of the WF Albright Institute of Archaeological Research in Jerusalem, who has spent years excavating at Megiddo.

'And then we realised, "Oh, it's in a maximum security prison, so we'll never actually be able to do anything with it."

'Now that the government has decided to move this prison, we can explore this really amazing and interesting part of the development of early Christianity in a way that we didn't think we'd be able to.'

The prison, whose inmates once included Hamas and Islamic Jihad militants, lies a few hundred yards south of Tel Megiddo itself, the ancient mound at which archaeologists have found walls dating back at least 7,000 years.

Between the prison and the hill is the largely unexcavated Roman Sixth Legion garrison, thought to have been built by the Emperor Hadrian.

The name Armageddon is believed to be a corruption of the Hebrew words Har Megiddo – Mount Megiddo.

Although small, the hill was the site of numerous ancient battles because it overlooks the Jezreel Valley, across which armies have marched since antiquity towards a pass leading to the Mediterranean.

The earliest written reference to Megiddo seems to have been during the reign of the Egyptian Pharaoh Thutmose III, who defeated Syrian and Canaanite states there in 1468 BC. It later fell to the Israelites, and then to the Assyrians in 733 BC.

In 1918, the British military commander General Edmund Allenby routed Turkish forces there and he later took the title Viscount Allenby of Megiddo and of Felixstowe.

But its fame derives principally from the apocalyptic final book of the New Testament, Revelation, which tells of 'the battle of that great day of God Almighty...And he gathered them together into a place called in the Hebrew tongue Armageddon'.

The current dig at the mound is led by Adams and Prof Israel Finkelstein, an Israeli archaeologist at Tel Aviv University.

'Megiddo was important because it sits on the international road which connects Egypt with Mesopotamia, with Damascus, with Anatolia. So whoever sits here controls the most important road of antiquity in the ancient world,' Finkelstein said.

Their team has used modern radiocarbon dating and laser-assisted distance measurements to precisely date and record the many layers of history on the tel, including monuments once thought to have been built in the era of King Solomon.

These, Finkelstein says, can now be attributed to the later era of Ahab, king of the northern kingdom of Israel in the 9th century BC.

The most important things was to date things accurately.

'One way is to date according to Biblical verses, and one way is to date according to radiocarbon studies. Biblical verses, with all due respect, are always problematic because there are questions regarding their author, their goals, the ideology behind the author and so on and so forth.'

But, he said, 'when you work with radiocarbon you are on solid grounds in your dating'.

Israeli tourist authorities are planning a complex on the site to combine tourism, archaeology, and nature hikes. Targeting Christian evangelicals in particular, they hope to draw 300,000 visitors annually, nearly double the current figure.

Much work remains.

'A prison of 1,000 dangerous prisoners will be moved and a new complex will be built in order to expose the mosaic and enable people from all over the world to come,' prison service spokeswoman Nicole Englander said.

Standing on Tel Megiddo as he supervised excavations into a Middle Bronze Age site, Adams said the area appears to have been a cultural melting pot two millennia ago, with Jews, Christians and pagan Romans all in the same spot.

That suggested interaction between early Christians and the Roman Empire were much more complicated than previously thought.

'Typically, we think of the Romans persecuting Christians,' he said.