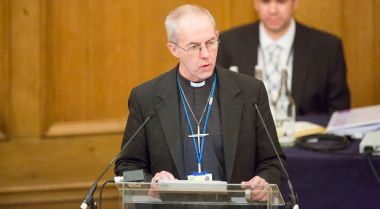

Justin Welby: Religious leaders are the key to ending extremism

Religious leaders have to "own the problem and develop the solution" to extremism, the Archbishop of Canterbury said yesterday.

In a speech at Queen's University in Belfast, Archbishop Welby reflected "on the nature of religiously-justified violence, and as a case study, on the nature, particularly, of the conflict we are facing with Daesh, or ISIS."

"For the first time in centuries, we have been facing major and global conflicts which have a very clear religious content," he said.

"For many years we've faced conflicts which have religious content locally, but not this same sense of global conflict. And, however evil it may be – and it is profoundly evil – we are facing such conflict in many parts of the world."

He called for "clear support for mainstream religious leaders of all faiths, in which the theological and ideological aspects of the struggle, which in the end are the only ones that will enable the supply of fighters to extremist groups to be cut off, are pursued and promoted relentlessly."

"Religious leaders have to own the problem and develop the solution," he added.

Since becoming Archbishop, Welby and his wife, Caroline, have visited all 38 provinces of the Anglican Communion around the world. They have come across Islamic violence, Christian violence, Hindu violence and Buddhist violence. "So both the Abrahamic and the Dharmic religions are deeply involved in a growth of radicalisation," he said.

In December last year, the Archbishop expressed his reluctant support for UK air strikes in Syria, telling the House of Lords that the criteria of a just war had been met.

He yesterday echoed this sentiment. Acknowledging that the debate is ongoing within the Church on the legitimacy of armed intervention, he said: "What I would say is that where an action is developed as a quasi-policing intervention against a group that is committing great crimes under international law, and where the objective is peace building and the resumption of stable communities to which refugees and IDPs can return, then, within the Christian tradition, I would suggest that it is justifiable."

However, he also said it would be "utterly wrong" to use force alone or even as the primary measure in the struggle against Islamic State. Welby has previously called for a holistic approach to the war in Syria, and yesterday warned that the global community must "engage in the right way, or we will ourselves sow the seeds of future conflict".

"In a struggle which is deeply ideological and theological, the response that we give must be based in a narrative of relationship, of protection, of order and of human flourishing that overwhelms the demonic narrative of disintegration and monolithic demonisation of the other, which is what faces us," he said.

The Christian response, Welby added, must be one of reconciliation, which he said "is the gospel". He called for a generous response to refugees, "but always with a clear strategy, incentive and aim of enabling return".

"To empty the Middle East of Christians removes diversity and sows trouble for the future."

He said it was time to "overcome this upsurge in religiously justified violence, which by its nature, in all of the great world faith traditions, perverts and abandons its original host by exempting itself from ethical principles, and caring nothing for human life."

Also highlighted by the Archbishop was the way in which the Western world seeks to "impose rights" on Muslim-majority countries across the globe. "Rights for women, for LGBTI people, are good rights to uphold. At the recent Primates meeting of the Anglican Communion, we condemned criminalisation of gay people, and quite rightly," he said.

"But it is also, as it is put to us quite often around the world, experienced as an imposition. Human rights, in the language in which it is often couched, may be good, but is presented in and on Western terms.

"The effect of these and many other aspects of global relationships is for those who are the objects of them – whether they are good or bad and many of them are good – the effect is humiliation; and that leaves the invisible wounds which reconciliation is called to bind, and the invisible needs that reconciliation is called to meet."

He suggested that this humiliation can be exploited by extremist groups who "use the hook of religion" to garner support for their radical aims.

He also pointed to the historic role Britain has played in aggravating the conflict in Iraq and Syria.

"History recognises that the situation in Syria and Iraq is artificially aggravated by the Sykes-Picot line, which is no more than a line in the sand drawn by those dividing up the Ottoman Empire towards the end of World War I. 1916, as it happens".

The Sykes-Picot line was agreed between the French and British governments.

"Our own responsibilities must be faced and acknowledged," Welby said. He also pointed to the Gulf wars and the "complexity and background of motivations of those countries currently involved in the region" as bearing responsibility for ongoing conflict in the Middle East.

But while it is "easy to call for Government action," he added, "The Church has its own responsibilities."

"We must lead in prayer, in love, in hospitality, in seeking human flourishing, in gracious and courageous action that demonstrates the beauty and hope of the Gospel of Jesus Christ, through religious communities that stabilise and serve," he said.

"In this struggle, our lives must respond to the Spirit's call and equipping."