Kim Davis: Should she be in jail?

When an irresistible force meets an immoveable object, it's usually time to yawn and suggest people stop playing word games.

When the irresistible force is the US government and the immoveable object is Kentucky clerk Kim Davis, things get a bit more interesting.

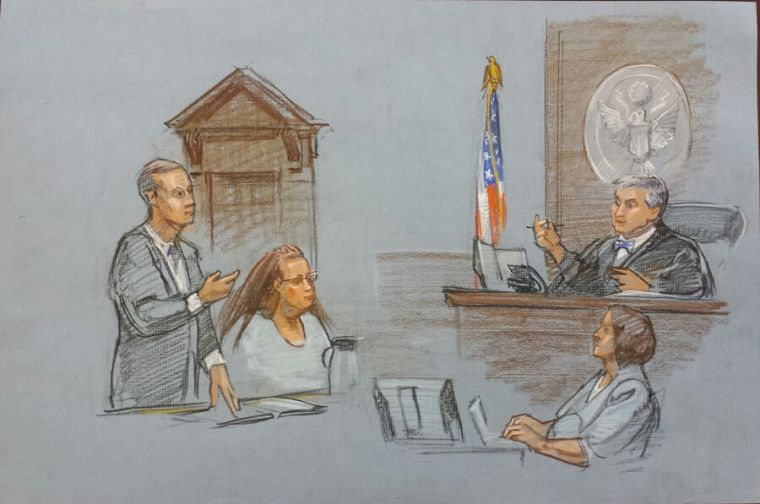

Davis is in jail for refusing to issue same-sex marriage licences because it would conflict with her beliefs as an Apostolic Christian. More precisely: she was ordered to do so by a federal judge, District Judge David Bunnings, and detained after repeated refusals.

There are some nuances here. Lawyers for the American Civil Liberties Union, who filed the motion to find Davis in contempt of court for her refusal to comply with the law, had asked Bunnings to fine her instead of imprisoning her because of the risk of making her a martyr. Bunnings, however, held that a fine would not be enough to ensure her compliance, and sent her to jail.

Why not just fire her? Because Davis is an elected official, not an employee. Her six deputy clerks were also threatened with contempt charges. Five of them caved, while the sixth, who continues to refuse, is Davis' son.

It's all a bit of a mess, and no one is particularly happy with the outcome. Davis is not backing down, but neither is Bunnings.

But even if she's breaking the law, should she really be in jail? Isn't there any room for a gracious compromise?

As things stand, the Davis case is another example of the conflict between traditional Christian morality and the agenda of the liberal secular state. It is being played out on both sides of the Atlantic – in the UK, in the case of hotel owners Peter and Hazelmary Bull, among others – and rarely seems to end well.

The tragedy is that it doesn't have to be this way. As long as both sides are prepared to be reasonable, there are ways round cases like this. They tend to end up in court when liberal secularism – which at its best simply wants a level playing field in which people do not face discrimination because of their sexuality, race or gender – becomes a proselytising force which imposes a moral agenda of its own.

The trouble is that the Davis case has become a symbol. It's a rallying point for conservative Christians who believe their faith is under threat. Franklin Graham called for prayer, saying: "We need more Americans who are willing to take a stand for religious freedoms and biblical values in our communities." Republican presidential candidates have weighed in too, with former Baptist minister Mike Huckabee saying that her imprisonment "removes all doubt of the criminalisation of Christianity in our country". Ted Cruz said that he stood with Davis "unequivocally", while Kentucky Senator Rand Paul said that it was "absurd to put someone in jail for exercising their religious liberty".

All these people have their own agendas. But that doesn't mean they don't have a point. How far should the state go in accommodating the personal beliefs of its functionaries? The absolute stickler for the supremacy of the law will say, "It shouldn't." The irresistible force of federal law will compel Kim Davis' obedience, or it will take away her ability to prevent other people (her deputy clerks) from doing so. The likes of Cruz and Huckabee have a point, just as the supporters of Peter and Hazelmary Bull had a point: should the state really be criminalising people because their personal morality comes into conflict with what the law has decided?

On the other hand, it's hardly reasonable for anyone to pick and choose which laws they will obey. That way the integrity of the state itself is compromised. Anarchy literally means "without law"; Davis, under the pretext of obedience to a higher law, is seeking to undermine her own civil society. A society in which each person is their own lawmaker is a society without laws at all.

The answer is, as so often in these cases, "We wouldn't start from here." There are certainly things that the State of Kentucky could do to reach a reasonable compromise. Conservative commentator Ryan Anderson argues in a New York Times article that a little judicious tweaking of Kentucky law would have removed the need for such a confrontation, allowing room for Davis to dissent but also same-sex couples to be issued with the licences they require. As another Republican nominee, Jeb Bush, put it: "There ought to be a way to figure this out. We shouldn't be pushing people out of the public square if they have deeply held views, nor should we discriminate against people, particularly, after this court ruling as it relates to sexual orientation."

In the Davis case, it's hard to see a satisfactory resolution. She cannot be allowed to disobey the law and shows no sign of being willing to compromise. Her case has become a proxy for the culture wars between liberals and conservatives, given an extra toxicity by the coming presidential campaign. There is no sign of the sort of generosity of spirit which would allow a whole-hearted commitment to shared civic values alongside a whole-hearted commitment to the ability to dissent from the views of the majority.

On neither side of the Atlantic is there much evidence of nuance, hinterland or maturity in this debate.