Lessons in the faith from slave trader-turned hymn-writer John Newton

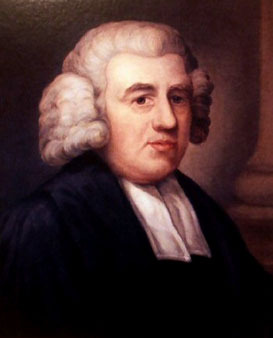

Few stories in Christian history are more dramatic than that of John Newton, whose life demonstrates the title of his most famous hymn, 'Amazing Grace'.

Newton was born in London in 1725 to a seagoing father and a devout mother. He followed his father to sea at the age of 11 but rejected his mother's faith, becoming a rebellious, reckless and immoral youngster.

He had an ability to find trouble: rejecting good jobs, being fired after six sea voyages and, aged 19, press-ganged into the Royal Navy. He deserted, was caught and given a public flogging.

Managing to leave the Navy, Newton became involved in the slave trade, shipping slaves from Africa to North America. It's a sad fact that slavery – a profitable and, in Britain, largely invisible trade – then aroused little controversy. Newton, having made many enemies, found himself left behind in Africa by his colleagues and was there imprisoned in chains and treated brutally for eighteen months.

When Newton was rescued in 1748, he showed no signs of repentance. Nevertheless, as he sailed back to Britain his ship was struck by a severe storm. As the vessel began to sink, Newton began to pray, throwing himself on the mercy of God. Somehow the ship was able to make it back safely to the British Isles. Although Newton later considered his prayer to mark the moment of his conversion, he was to write, 'I cannot consider myself to have been a believer, in the full sense of the word, until a considerable time afterwards.'

However, change had started and Newton began to pray and to read the Bible.

In 1750, Newton married Polly Catlett, with whom he was to have 40 years of happy, if childless, marriage. He returned to serve on slave ships, making three voyages as captain and seemingly ignoring any inconsistency between his trade and his faith.

At the age of 29, after ill health, Newton gave up seafaring and instead took a job in the port of Liverpool. There, his Christian life started to blossom and he came under the influence of those great preachers of the Methodist revival, John and Charles Wesley and George Whitefield. Newton's life changed and he became involved in evangelical fellowships and in organising Bible study. He sought ordination in the Church of England but for several years was rejected because of his lack of a degree and the suspicion that he had acquired Methodist 'enthusiasm'.

Finally, aided by an influential supporter, Newton was ordained and became curate of Olney in Buckinghamshire. A lively, committed and caring pastor who taught the Bible and preached appealing and relevant sermons, he trebled the size of his congregation. He also wrote books that brought him to the attention of the wider public.

The poet and hymnwriter William Cowper moved to Olney and he and Newton became close friends, something that was to prove an enormous help to the depressive Cowper. Together, they set about writing hymns. Newton's contribution included many hymns that remain popular including 'Amazing Grace', 'How Sweet the Name of Jesus Sounds' and 'Glorious Things of Thee Are Spoken'. Although technically Cowper may have been the finer poet, Newton demonstrated a remarkable ability for using simple language.

After 16 years of fruitful ministry in Olney, Newton moved to a City of London church in 1780. There, at the heart of the nation, he was able to be a powerful influencer, encouraging, counselling and promoting in every way, a vibrant evangelical Christianity. When the young and promising politician William Wilberforce became converted and was tempted to leave politics for the church, Newton encouraged him to stay in Parliament and 'serve God where he was'.

By now the national mood was turning against slavery, and Newton, still grieved over his own involvement decades earlier, wrote a powerful pamphlet – 'Thoughts Upon the African Slave Trade' – based on his own experiences. It circulated widely and was greatly used in helping Wilberforce in his ultimately successful campaign against the slave trade.

In his final years, Newton became perhaps the senior statesman of the evangelical church in Britain, doing whatever he could to promote the gospel; supporting ministers across denominations and helping to found both the Church Missionary Society and the Bible Society. Newton died in 1807 aged 82, after 50 years of service to Christ and just months after slavery was ended across the British Empire.

There are many things to challenge us in John Newton's life but to me the most striking are those that arise out of his conversion. Let me offer you four thoughts.

First, we see the priority of conversion. The transformation of Newton from the messiest of lives to a gracious servant of God teaches the life-changing potential of an encounter with Christ. Ultimately, Christianity is not a matter of morality; it's about Jesus changing lives.

Second, we see the principle of conversion. Newton's story reminds us that while we cannot save ourselves, God can and does. In the words of 'Amazing Grace', Newton came to God as an undeserving 'wretch' who was 'lost' and 'blind' yet Christ saved him.

Third, we see the process of conversion. We all love stories of dramatic conversion with overnight changes of behaviour. They happen but so do seemingly protracted conversions like Newton's. We need to be reminded that sometimes it may take a long time after the seed is planted for the flower of faith to blossom.

Finally, we see the product of conversion. Newton received abundant grace. But it's important to note that, having received grace, he shared it with others. The rich grace God gave to Newton spilled over into many lives and into the world.

Among John Newton's last recorded words were these: 'My memory is nearly gone but I remember two things: that I am a great sinner and Christ is a great saviour.' Amen.