'Life has become intolerable': Fleeing Pakistan because you're the wrong type of Muslim

"We know you are an agent from the United States," said the voice on the end of the phone.

A few days later another threat, from another blocked number. Over the next three years the threats increased. Some promised injury. Some death. And then they began calling his work phone. He resigned and moved town for the safety of his colleagues. But the phone calls quickly caught up with him.

Then one day he was stopped by a motorbike en route to work. "I thought he was just asking me something so I stopped. Then I realised they might be kidnapping me. Then I saw the pistol.

"They told me: 'You have two weeks. If you go the police our people are there and we will know.'"

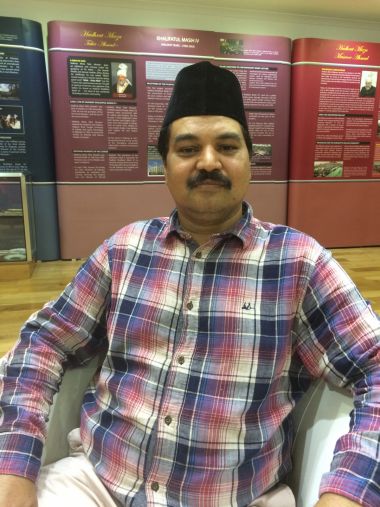

Dusk is falling on the vast Baitul Futuh mosque in south London. Muzaffer Tahir is an asylum seeker, fleeing Pakistan because he is the wrong type of Muslim. As an Ahmadi he is even more hated than local Christians.

The sun gradually sets and it is almost time to break the fast. But the animated Tahir shows no sign of weakness as he describes life in Pakistan as part of the Ahmadiyya Muslim community.

A law was passed in 1978 that meant Ahmadis, a sect of Islam that believe the promised Messiah has already come, could not describe themselves as Muslims. This has allowed hardline clerics to preach against Ahmadis who they consider a dangerous cult.

In the past three months alone five Ahmadis have been killed in targeted attacks on the streets of Pakistan. An organisation known as the "finality of the prophet Mohammed" has been set up specifically to eradicate the Ahmadiyya community and many now see it as their religious duty under Allah to kill Ahmadi Muslims. Their names and addresses are handed out on the streets so any hope of secrecy is destroyed.

A minute after the designated time of sunset, dates are brought in for the Iftar, the breaking of the fast during the Islamic month of Ramadan. As we pass round the dates and fruit salad to start the meal, Mansoor Shah, the vice-president of the Ahmadiyya community in Morden where Tahir stays, takes over.

"The poison that has been spread across the population of Pakistan is so widespread that they say Ahmadis are agents of the Americans, the Israelis and British. All these three are held in extreme contempt in Pakistan. So the entire population has turned against the Ahmadis.

"Even the syllabus has been re-written so the Ahmadis are discriminated," he said. "Life has become intolerable."

Gathered round the table along with Tahir and Shah are Fareed and Mahmood, two other members of the Ahmadiyya community in south London. We share a traditional meal together and discuss how this minority sect that was founded in the nineteenth century to follow the teaching of Hazrat Mirza Ghulam Ahmad has developed. The UK now hosts more than 30,000 Ahmadi Muslims after the first mosque was built in London in 1926. Such is the extent of persecution, the Ahmadi leader, or Caliph, had to flee Pakistan and move his main base to London in 1984. For the last three decades, the UK capital has been the home of the global Ahmadiyya community.

After the meal Fareed, Mahmood and Tahir offer to show me round the mosque as it fills up for the evening prayers. The £15 million site can hold up to 10,000 people with two vast prayer halls, one for men and one for women, as well as a sports hall, a library and a museum.

The air is heavy as the prayer chants ring across the evening air. It is the eve of the EU referendum and a storm is gathering in London. But for Tahir even the looming prospect of Brexit could not make his situation much worse.

He sought asylum in the UK in 2013. But in 2016 his case is still far from being resolved. Tahir becomes emotional as he describes his arrival in the UK. He was thrown into a detention cell and left for 28 days in effective imprisonment. When he was finally given an interview he "immediately felt the translator was not translating properly".

He says he tried to answer the caseworker's questions directly in his broken English but was shouted at by the interpreter and forced to speak through him. His case was thrown out but he appealed.

Sometimes translators do not accurately translate because they are unprofessional and do not speak good enough English, he said. Sometimes it is because they do not have a proper grasp of the religious topics in question so cannot translate fairly. But in other cases it is because they "belong to another sect of Islam", he said and use the opportunity to deliberately jeopardise Ahmadi cases.

"Some interpreters are from another sect and they intentionally don't want to properly translate," he said. When asked whether he thought this had been a factor in why his case was thrown out, Tahir said: "Yes, I think so."

Home office interpreters are hired from outside companies and many are Muslims from the mainstream sects of Islam that so despise Ahmadis. Whether their errors are deliberate or due to inadequate skills, they can mean life or death in a case such as Tahir's.

A recent report by the all party group on religious freedom highlighted the "lack of professionalism" from some home office interpreters.

"At best it is ignorance and at worst we have heard of cases where it has been intentional persecution and an intentional undermining of the case," said Bishop Angaelos, chair of the Asylum Advocacy Group which helped compile the report. He told Christian Today this was the exception rather than the rule but said it "needs to be investigated at once".

The report said there was a clear disparity between what the home office said in its official guidance and what actually happens in interview rooms.

One solicitor quoted in the report said: "There is already sufficient and perfectly sound guidance formulated by the Home Office, and by notably the UNHCR...for good decision making in the area.

"But decision making continues to be very poor."

When asked for a response, a home office spokesperson simply said: "All asylum applications are carefully considered on their individual merits, in line with the UK immigration rules."

Tahir, whose story was used in the report, looks tired as he takes off his shoes to enter the giant hall for evening prayers. He had a successful career and worked with refugees for various NGOs in Pakistan. Like millions others around the world, he has lost everything as he fled persecution because of his religion. He now lives in an everyday uncertainty of not knowing whether he will be sent back to almost certain death or whether he will be allowed to settle. The date for his hearing was originally set for 28 February 2015. Then it was moved to 28 October 2015. Now it has been set for March 2017. "If I am still alive then," he says. He is only half joking.

His wife and children are still in Pakistan and unable to join him. She has been ill recently, he told me, but he could not visit for fear his enemies would find out about it.

"I worked with refugees in Pakistan for more than ten years," he said. "I never thought one day I would become one."