Mark Woods: Not marching for Boko Haram killings doesn't mean we don't care

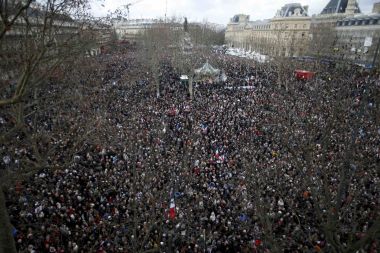

The killings in France were awful, awful. The demonstrators who turned out to express their love, support and solidarity – around 4 million of them – were doing a good thing. It was heartening, moving and hopeful.

You wouldn't think so, though, by some of the reactions. The problem was that the Charlie Hebdo and Jewish supermarket killings in France, and the exhaustive coverage of motives and methods that followed, coincided with news of an even worse atrocity. This one was in Nigeria, and it was ghastly: Boko Haram conducted its worst ever massacre in the town of Baga in the northern Borno State. The figure of 2,000 dead is being used, but the bodies are said to be too many to count.

Around 2,000 in Baga; 17 in Paris. So which one should get world leaders marching arm in arm, solemn commitments to peace and justice, and 4 million people swearing eternal love and fraternité?

It's the discrepancy between these figures that has got people fired up. Why, asks the Guardian, did the world ignore Boko Haram's Baga attacks? Put in #bagatogether on Twitter, for instance, and there's a deluge of criticism directed both at the media and at world leaders. The media are accused of ignoring Nigeria because it's a long way away, it's a developing country and anyway – the accusation runs – editors just think, "That sort of thing happens all the time in that sort of place."

Well, you would have to be a pretty dreadful specimen of a human being, not just of a journalist, if you really thought like that. But that doesn't mean that there's no case to be answered. As an Amnesty blogger puts it: "Why aren't global leaders linking arms in Abuja calling for an end to the merciless blood spill, abductions, rapes and other grotesque crimes committed by this terrorist group?"

Let's be honest and admit that the media doesn't always get it right. Yes: some stories are easier to report than others – and Boko Haram territory in Northern Nigeria is hard, with poor communications, and a dangerous beat to cover.

Let's admit too that governments and the world leaders they represent are selective in the causes they support. It is hard to believe, for instance, that Israel's Prime Minister Benjamin Netanyahu didn't have an eye to both domestic and foreign politics when he turned up in France and assured Jews there that they would always be welcome back home: the Palestinian issue has become so toxic for Israel that highlighting Islamist atrocities plays very well for him.

More generally, the genuine moral engagement that many politicians feel in some of the great questions of our time will always – and rightly – be tempered by considerations of what is actually achievable. Windy rhetoric is pointless. Sooner or later, someone – usually a journalist – will ask, "So, what are you going to do?" Not one of the leaders gathered in Paris to mourn the killings would find it politically possible to send an effective army to fight Boko Haram, even if the Nigerians wanted them to.

But still: comparisons between the two – though they are undeniably plausible – are wrong, for three reasons. First, the outpouring of grief and its media coverage in Paris was real, and journalists had a duty to report it. It was at the heart of France's circles of concern, while Nigeria – inevitably – is further out. There is nothing wrong with feeling more deeply for those who are closer to us. It is a natural, human instinct. For France to have said, "We will not march, because elsewhere in the world there are worse tragedies than ours," would have denied them something precious – and because France is a near neighbour and Britain has a large French population, it was our story too.

Second, it doesn't need a cynical dismissal of Boko Haram attacks as 'normal for Nigeria' to recognise that the Paris shootings were a profound and genuine shock to French and European society. This had not happened before. Its circumstances were peculiarly horrible. It was an attack on a cherished tenet of Western culture, free speech. It made people not only mourn, but think; and neither the mourning nor the thinking is over yet. "After the first death, there is no other", wrote Dylan Thomas (A refusal to mourn the death of a child, by fire, in London). Under the scourge of Boko Haram, Nigeria's first death was years ago. This is France's first, at least of its kind; it should be allowed its mourning.

Third, why pick on Nigeria? What do the Twitter warriors think is happening in the Eastern Congo, or in North Korea, or in Syria or Iraq? The truth is that terrible things happen all over the world, all the time. Journalists report them as best they can and politicians try to deal with them as best they can. How are they supposed to judge which are more important? By body count, age of victims, geopolitical repercussions? Surely nothing so calculated – but somehow a judgment has to be made.

So does the unholy juxtaposition of the two events, in Paris and in Baga, simply have nothing to say to us? Of course not: but simplistic and confected outrage at the supposed callousness of press and politicians is neither fair nor helpful. We should have the honesty to admit that some things touch us more nearly than others: but out of that honesty, the Paris killings will have made us think more and pray harder for Nigeria. That's a result.