'If one imagines for a moment that Bishop Bell were one's own father, the point is clearly made. If a system is not good enough for our own fathers, then it is not good enough for anyone.' (paragraph 46, p. 12, Bishop George Bell Independent Review).

The long-awaited Independent Review of the Bishop George Bell Case, conducted by Lord Carlile of Berriew CBE, QC was published on December 15. As one of the campaigners for transparency in this case - namely for the Church of England to disclose exactly how it reached its decisions in relation to a single complaint of sexual abuse made against Bell, decades after his death - Alex Carlile's Review is a fulsome vindication of the need for a complete overhaul of the practice of the Church. The report shows that justice was not served - either to Bishop Bell, or to the woman known as 'Carol'. The report shows - damningly, alas - that the entire process by the Church of England was conducted through the lens of reputational management. Appropriate legal expertise was not used. Assumptions were made: guilty unless proven innocent. Dreadful and egregious errors of procedure were made, revealing a culture of shoddy amateurism. When challenged on this, the evolving debacle was further compounded by assertions that a 'proper' process and 'robust' investigation had been undertaken. They hadn't. Not remotely.

It is crystal clear from reading the report that the accusations were badly handled from the beginning, and that once the accusations were in the hands of the 'Core Group', members not only lacked commitment to prioritise their participation but lamentably failed in their duty to determine the facts. The whole process administered by the Church of England then descended into a tragic, incompetent farce. In all this, some are continuing to insist that Bishop Bell was, in all probability, guilty - when in the end, there is still only the testimony of one person, with no corroboration.

Yet it is clear, reading between the lines of Lord Carlile's report, that in investigating how the Church handled the allegations they discovered enough to challenge their veracity. In what follows, therefore, I highlight ten key findings from Lord Carlile's Independent Review, and suggest that the Church of England resolves to address these as a matter of urgency:

'It follows that, even when the alleged perpetrators have died, there should be methodical and sufficient investigations into accusations levelled against them....I have concluded that the Church of England failed to institute or follow a procedure which respected the rights of both sides. The Church...has in effect oversteered in this case. In other words, there was a rush to judgement...' (para. 17-18, p.5). The Church of England acted rashly and hastily, and it needs to correct this knee-jerk reaction in future, if justice is to be served. In the case of Bell, injustice has been manifestly perpetrated.

- '...in this case the Church adopted a procedure more akin to the second extreme: that is to say, when faced with a serious and apparently credible allegation, the truth of what Carol was saying was implicitly accepted without serious investigation or enquiry. I have concluded that this was an inappropriate and impermissible approach and one which should not be followed in the future...in my view, the Church concluded that the needs of a living complainant who, if truthful, was a victim of very serious criminal offences were of considerably more importance than the damage done by a possibly false allegation to a person who was no longer alive...' (para. 43-44, p. 12). The Church of England essentially assumed Bishop George Bell was 'guilty until proven innocent'. The Church of England needs to ask how it protects those who are the victims of false allegations.

- 'Importantly, the Church should not put its own reputation before that of the dead...the complainant is not a "survivor"...' (para. 52, p. 13/14). The 'Core Group' made dreadful assumptions. Namely, that no-one who had worked with Bell was still alive. They did not contact Bell's relatives (even though George and Henrietta had no children of their own). The 'Core Group' put the reputational risk to the Church as a higher priority than serving justice, and getting to the truth of the matter. The complainant is repeatedly referred to by the Church as a 'victim' or 'survivor' - but no facts or testimony have come to light, other than the claims made by the complainant - that would corroborate the appropriate use of such pejorative labels.

- In paragraph 138, p. 32 we are told there was no real police enquiry into the case. Yet the Church of England had tried to 'spin' this, to suggest that any enquiry would have found Bell guilty.

- '...despite mention of the importance of ensuring that the deceased accused person received a fair hearing, absolutely nothing was done to ensure that his living relatives were informed of the allegations, let alone asked for or offered guidance. Nor were any steps taken to ensure that Bishop Bell's interests were considered actively by an individual nominated for the purpose. I regret that Bishop Bell's reputation, and the need for a rigorous factual analysis of the case against him, were swept up by a tide focused on settling Carol's claim[s] and the perceived imperative of public [reputation]...' (para. 142, p.33). The Church of England, in other words, only listened to the complainant, and took those accusations at face value. No system of justice in the entire world could ever regard this as fair, decent or true. The process run by the Church of England has more in common with a trial scene from Alice in Wonderland. No system of defence or justice for Bell was designed or enacted (para. 155).

- Paragraph 178, pages 46-48. Professor Maden, an expert on 'false memory syndrome', comments extensively on the case. He closes his remarks by stating that 'I have no doubt that [the complainant] is sincere in her beliefs. Nevertheless it remains my view that the possibility of false memories in this case cannot be excluded. The facts are for the Court to determine. I do not believe that psychiatric or other expert evidence is likely to be of further assistance in establishing whether or not these allegations are true...'. Some members of the 'Core Group' did not read the whole of Professor Maden's report, so 'a fuller evidential investigation' that might have been called for to test the complainant's claim never occurred. The 'Core Group' even failed to contact the complainant's wider family (whom 'Carol' said she was close to), and who could have perhaps provided corroborating or dissenting testimony.

- Two completely credible witnesses came forward. A woman identified as 'Pauline' and Canon Adrian Carey (paras. 214-228, pages 54-56). Neither corroborates Carol's testimony. Neither can recall such a young girl being present with the regularity and frequency 'Carol' claims. Carey, Bell's Chaplain, lived in the Bishop's Palace with Henrietta and George Bell. Pauline, a child who lived in the palace and played in the gardens during the same years that 'Carol' claims that her abuse took place, does not recall any child like 'Carol': 'Pauline and her mother lived in the palace itself. They shared a bedroom on an upper floor, and they had a sitting room of their own. Pauline went to school locally, to an Infants' School then a Primary School. She passed the 11 Plus. At that point her mother obtained a job in another household and they left the palace. She remembers and named correctly other staff working in the palace and living there or in the grounds. She remembered the name of [the person Carol visited]. However, she did not recall Carol. This does not mean that Carol was not there from time to time: however, if Pauline is correct it would suggest that [Carol's] visits were not so frequent as to have made her a significant presence...'.

- Despite the lack of evidence against Bell - remember, still just one complainant, and the 'Core Team' having failed to take account of relevant expertise (i.e., legal, psychiatric, historians, Bell's biographer, etc.), or contacted living witnesses to test the claims made by 'Carol' see paras. 248-252, p. 64) - nonetheless, 'Carol, and the wider public, were left in no doubt whatsoever that it was accepted that Bishop Bell was guilty of what was alleged against him. The statement provided the following conclusions: (i) The allegations had been investigated, and a proper process followed. (ii) The allegations had been proved; therefore (iii) There was no doubt that Bishop Bell had abused Carol...'. (para. 237, page 61). Lord Carlile later adds: 'I regret that the Core Group failed to carry out sufficient investigation into the facts' (para. 244, p.63).

- The 'Core Group' that investigated the case against Bishop Bell was found to have been 'set up in an unmethodical and unplanned way, with neither terms of reference nor any clear direction as to how it would operate. As a result, it became a confused and unstructured process, as several members confirmed. Some members explicitly made it clear to me that they had no coherent notion of their roles or what was expected of them. There was no consideration of the need for consistency of attendance or membership. The members did not all see the same documents, nor all the documents relevant to their task. There was no organised or valuable inquiry or investigation into the merits of the allegations, and the standpoint of Bishop Bell was never given parity or proportionality. Indeed, the clear impression left is that the process was predicated on his guilt of what Carol alleged...'. (para. 254, p. 65). You can only read this as a vote of total 'non-confidence' in the Core Group. It is not so much a case of what few things they got wrong, as discovering that they got almost nothing right. This was a complete failure of process.

- So Lord Carlile concludes: 'in my judgement the decision to settle the case in the form and manner followed was indefensibly wrong' (para. 258, p. 66).

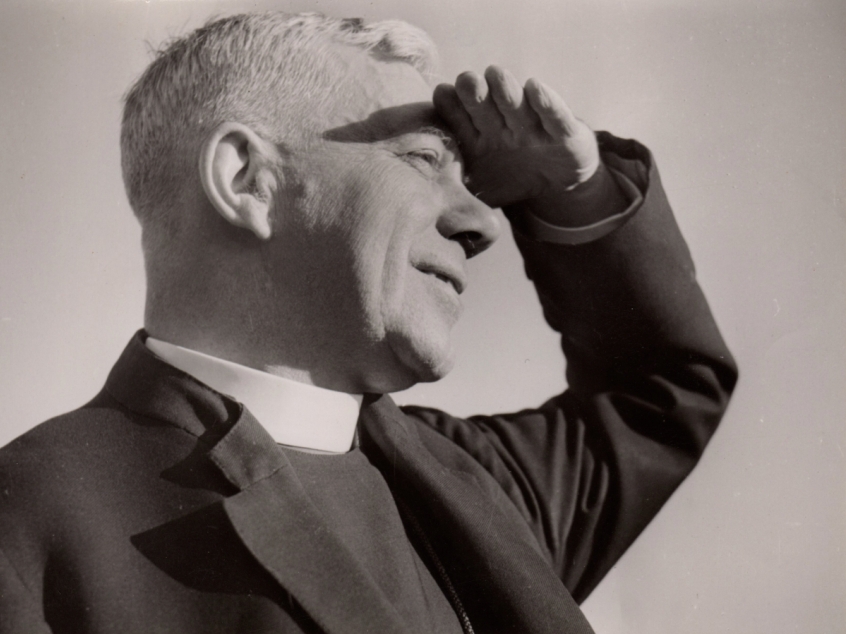

Bishop George Bell Pic courtesy of Jimmy James Since the publication of the Carlile Report, the Archbishop, Church of England National Safeguarding Team and the Bishop of Chichester have all been defensive. They recognise that there are criticisms. But they continue to speak and behave as though they got the right result - merely via a flawed methodology. I am reminded of the quote from Alan Partridge: 'You know, a lot of people forget that for the first three days, the cruise on The Titanic was a really enjoyable experience.'

On the October 21, 2015, I had been rung by the then Secretary-General of the Archbishops' Council and of the General Synod of the Church of England, Sir William Fittall. It was Fittall who told me, over the phone, that a 'thorough investigation' had implicated Bishop George Bell in an historic sex-abuse case, and that the Church had 'paid compensation to the victim'. Fittall added that he was tipping me off, as he knew we had an altar in the Cathedral dedicated to Bell, and that Bell was a distinguished former member of Christ Church.

Fittall asked what we would do, in the light of the forthcoming media announcements. I explained that Christ Church is an academic institution, and we tend to make decisions based on evidence, having first weighed and considered its quality. Fittall replied that the evidence was 'compelling and convincing', and that the investigation into George Bell has been 'lengthy, professional and robust'. I asked for details, as I said I could not possibly make a judgement without sight of such evidence. I was told that such evidence could not be released. So, Christ Church kept faith with Bell, and the altar, named after him, remains in exactly the same spot it has occupied for over fifteen years, when it was first carved.

What we now learn from Independent Review of the Bishop George Bell Case is that evidence against Bell is, at best, flimsy. Charles Moore, writing in the Daily Telegraph, (December 16, 2017) notes that the Church of England:

...would only be reverting to the principle upon which justice is based – that a person is innocent unless proved guilty. It says it accepts the report's finding that its procedures were wrong. In morality and logic, it must concede that its decision to destroy Bell was wrong too. This, I had expected, was what Archbishop Welby would now do. He is a brave man and I know, from conversations with him, that he is deeply anguished both by child abuse and by false accusations of child abuse. He tries harder than most princes of the Church to get alongside those who suffer.

Yet this is what he said on Friday. After acknowledging the failure of Church procedures, the Archbishop spoke of Bell's 'great achievement' as a defender of the persecuted and added: 'We realise that a significant cloud is left over his name ... He is also accused of great wickedness. Good acts do not diminish evil ones, nor do evil ones make it right to forget the good. Whatever is thought about the accusations, the whole person and the whole life should be kept in mind.'

I'm afraid this is a shocking answer. The Archbishop must know that what people now think about the accusations depends very much on him. His own report tells him they were believed on grossly inadequate grounds. Does he cling to that belief or not? He invites us to balance the good and evil deeds of men; but there is no balance here. The good Bell did is proved. The evil is an uncorroborated accusation believed by the religious authorities because it makes their life easier. We have been here before – in the life of Jesus, and in the reason for his unjust death.

Bishop George Bell was one of the towering figures of twentieth century Anglicanism. He was a saintly man, of prodigious theological calibre. He befriended the Dietrich Bonhoeffer and Martin Niemöller other leaders of the German Confessing Church. Bonhoeffer's last letter, before he was executed by the Nazis in 1945, was to Bell. Niemöller sought out Bell as soon as the Second World War ended. And it was Niemöller, you may recall, who is remembered for this quotation:

First they came for the Socialists, and I did not speak out— because I was not a Socialist. Then they came for the Trade Unionists, and I did not speak out— because I was not a Trade Unionist. Then they came for the Jews, and I did not speak out— because I was not a Jew. Then they came for me—and there was no one left to speak for me.

But many of us did speak out for Bell - because of the pitiable processes and procedures he has been subjected to. This must now be fully overturned by the Church of England, and Bell's name and reputation fully restored. No member of the 'Core Team' investigating Bell would ever allow their own deceased father to be treated like this. For a Father in God such as Bishop George Bell to be subjected to such reputational traducing, long after his death, requires an unambiguous capitulation on the part those who bear responsibility for this.

The Very Revd. Professor Martyn Percy, is Dean of Christ Church, Oxford.