The writer of the Letter to the Hebrews reminds Christians that they are surrounded by a great "cloud of witnesses." (NRSV) That "cloud" has continued to grow in size since then. In this monthly column we will be thinking about some of the people and events, over the past 2000 years, that have helped make up this "cloud." People and events that have helped build the community of the Christian church as it exists today.

Women's voices are often muted or marginalised in history. This was more so in the Middle Ages than today, even though huge numbers of women, as well as men, played an active part in the life of the medieval Christian community.

There were a very large number of clerics in the medieval English church, perhaps 33,150 (male) priests in 1250, in 9,500 parishes. To this should be added 7,600 monks, 3,900 regular canons, and 5,300 friars. These may have made up as much as 5.6% of the adult male population in 1200. Those living in communities, according to a 'rule' of conduct, are often described as the 'religious.'

But what about the 'religious' women? There were about 1,500 men and women working in hospitals as part of a religious order, and perhaps as many as 7,000 nuns. Even as late as 1500 (in the generation before the Reformation) there were about 26,500 clerics in parishes and about 10,000 monks, canons and friars combined, plus 2,100 nuns. Together, they made up about 2% of the total population.

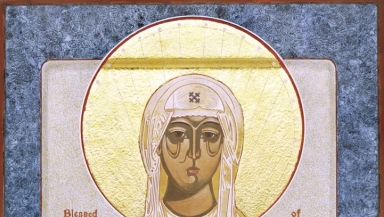

The bottom line is that there were huge numbers of medieval women actively involved in celibate communities. The problem is that we don't hear anything like the volume of women's 'voices,' compared to male 'voices.' At times, though, they do speak to us, perhaps most famously Julian of Norwich (1342–c.1416).

Julian – named from St. Julian's Church in Norwich – wrote a remarkable book entitled The Revelations of Divine Love, now widely acknowledged as one of the great classics of the spiritual life. This remarkable book arose from a series of sixteen visions that she received on May 8, 1373. At the time she thought she was on the edge of death and, in this state, she had a vision in which she saw Christ bleeding in front of her. From this visionary experience she received an extraordinary insight into Christ's sufferings and his love for us.

Julian's book has survived in two versions. The first – and shortest – was written shortly after the visions. The second – the longest – was written twenty years later. This longer version includes her meditations on what she had been shown in the original visions.

Julian was an anchoress, that is a woman who lived a life of prayer and meditation voluntarily shut up alone in a cell. In the case of Julian, this was attached to St. Julian's Church in Norwich and she also had a maid who lived in a room next to the cell. Julian gave advice to those who came to speak with her, through a small window. She was, therefore, at the centre of community life but also permanently separated from it.

When an anchoress, such as Julian, was sealed into her cell, a priest would recite funeral prayers: the 'office of the dead.' It signified that she was dead to the world. And yet, as we shall see, the world could come to her for advice. St Julian's church was situated next to one of the busiest roads in medieval Norwich. It is no anachronism to say that she was a medieval 'influencer.'

Julian of Norwich's book is a remarkable example of a woman's voice that has survived from the Middle Ages, and one which provides an insight into her walk with God. But Julian's 'walk' was a physically tightly circumscribed one. She did not literally 'walk' anywhere, apart from around the enclosed space in which she lived for many years. Her insights are no less revealing and moving because of this – but they are those of one who was, quite literally, shut off from the everyday activities of the world. Which makes one wonder what those 'out in the world' might have said, if their voices had been recorded for posterity.

There are some exceptions to the marginalisation of the voices of medieval women in this country. Many readers will have come across the famous 'Wife of Bath' in Chaucer's Canterbury Tales. But this, of course, is a woman who was given a 'voice' by a man. Which makes it all the more remarkable when we can actually hear a woman's words in her own voice. Even better, when she talks us through the highs and lows of her turbulent life in the heat and dust of everyday life. And it gets even more engaging when the woman in question is Margery Kempe!

And this is where the arc of the lives of two remarkable women cross. This is because, in 1413, Margery Kempe visited the anchoress, Julian of Norwich. She did so because she needed reassurance about the authenticity of revelations and insights that, like Julian, she believed she had received from Christ. It was an extraordinary example of a friendship of two women who were 'sisters in Christ.' But, while one of them watched the world through the narrow window in the wall of an anchoress' cell, the other was out there in the world.

Margery Kempe – Pilgrim

Born Margery Brunham in King's Lynn (then Bishop's Lynn), Norfolk, in about 1373, Margery was the daughter of John Brunham, a merchant in Lynn, and five times mayor of the town. He was also a Member of Parliament. Margery was married at the age of 20 to a local Norfolk man named John Kempe, with whom she had fourteen children.

Following the birth of her first child, Margery fell ill and may have suffered from post-natal depression. She later said she suffered at this time from "madness," which culminated in a life-changing vision of Christ at her bedside. According to Margery, he asked her: "Daughter, why have you forsaken Me, and I never forsook you?"

It was the beginning of an extraordinary journey – but it was not an easy road. Following the vision, she decided to open first a brewery and later a grain mill. Both enterprises failed.

Though she had tried to live a more holy life after her vision, she was tempted by sexual desire and jealousy of neighbours for some years.

In the end, she gave up her business enterprises and dedicated herself completely to the spiritual calling which she felt her visions required. In order to do so, she began to live a chaste marriage with her husband and began to make pilgrimages around Europe. It was the start of her pilgrim life.

On these journeys she visited Rome, Jerusalem, and Santiago de Compostela (the shrine of St James in Spain). She wrote of her experiences – or rather dictated them to scribes – in The Book of Margery Kempe. In this book she recounted her experiences on these spiritual journeys, the final section including a number of prayers. During this time Margery tells how she had a number of conversations with Christ. Her faith was a very personal one and, according to her own account, was one that involved a lively interaction with Christ. However, Margery was a complex character and not everyone reacted well to her rather unorthodox – and, at times, very volatile and emotional – behaviour. Her loud wailing and sobbing, in response to her spiritual experiences, both unnerved and irritated many of those around her.

As well as describing her journeys and spiritual experiences, she also used her book to record the conflicts she had with church authorities – many of whom did not quite know what to make of this woman. Was she mad? A heretic? Or saintly? Opinions were clearly divided! She was tried on different occasions for allegedly reading scripture (generally a man's role in the medieval church), for teaching and preaching on scripture and faith (definitely a man's role), and wearing white clothes which was considered inappropriate as she was no longer a virgin. In each case she succeeded in clearing herself of charges laid against her.

Between 1413 and1420 she also visited important sites and church leaders in England. These included visits to Philip Repyngdon, Bishop of Lincoln, Henry Chichele, Archbishop of Canterbury, and (as we have seen) the anchoress Julian of Norwich. The last section of her book deals with a journey she made in the 1430s to Norway and to the Holy Roman Empire. Margery died in about 1438.

On any analysis, Margery Kempe was a complex and amazing person. She clearly lived very close to the edge of what was accepted as orthodoxy. Her life reveals a tension between the strict authority of the church's hierarchy and a fifteenth-century search for a more personal and intimate faith. In her own words she clearly felt that she had experienced a faith that was as orthodox as it was personal.

In the opening of her book, she summed up the essential core of her belief and experience. It is worth reading in the Middle English of the original words of Margery herself. Firstly, to get a feel for the 'voice' of this remarkable Christian woman. Secondly, because, if read aloud, it is a reminder of how accessible Middle English is (regardless of how it looks). This was how Margery summed up the beginning of her walk of faith:

"Here begynnyth a schort tretys and a comfortabyl for synful wrecchys, wherin thei

may have gret solas and comfort to hem and undyrstondyn the hy and unspecabyl

mercy of ower sovereyn Savyowr Cryst Jhesu, whos name be worschepd and magnyfyed

wythowten ende, that now in ower days to us unworthy deyneth to exercysen hys nobeley

and hys goodnesse."

The words of Julian and of Margery give us a rare glimpse into the faith of medieval women. They remind us of the sincere and personal nature of that faith as they strove to walk with God and face the challenges of life. They provide a rare female 'voice,' which expresses something of the Christian faith of the medieval Catholic world. And they remind us that – for all the problems besetting the church at the time – medieval Christians, in their walk with God, were not just marking time, waiting for the Reformation to happen!

Martyn Whittock is an evangelical historian and a Licensed Lay Minister in the Church of England. As an historian and author, or co-author, of fifty-five books, his work covers a wide range of historical and theological themes. In addition, as a commentator and columnist, he has written for several print and online news platforms; has been interviewed on TV and radio shows exploring the interaction of faith and politics; and appeared on Sky News discussing political events in the USA. Recently, he has been interviewed on several news platforms concerning faith and the Crown in the UK, and the war in Ukraine.

His most recent books include: Trump and the Puritans (2020), The Secret History of Soviet Russia's Police State (2020), Daughters of Eve (2021), Jesus the Unauthorized Biography (2021), The End Times, Again? (2021) and The Story of the Cross (2021). His latest book, Apocalyptic Politics (2022), explores the connection between end-times beliefs and radicalized politics across religions, time, and cultures. He has also written several books on medieval history, including A Brief History of Life in the Middle Ages (2009).