Negotiators grab head start on monumental climate challenge

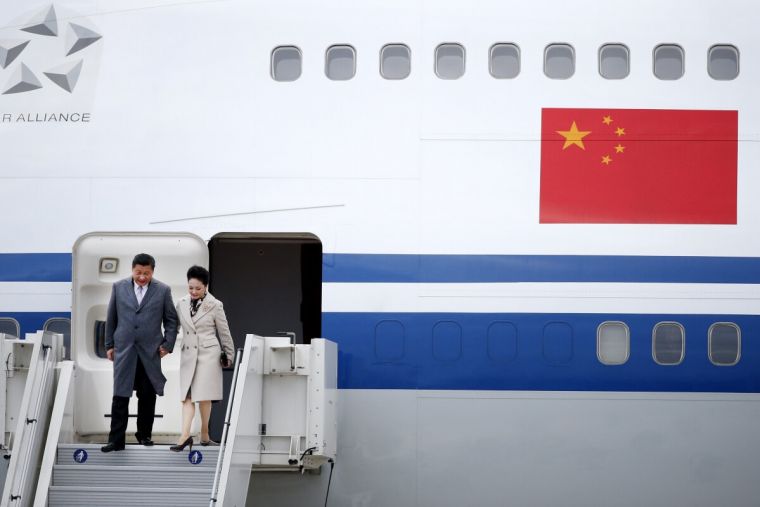

Senior negotiators from almost 200 nations on Sunday began thrashing out a new global deal to curb climate change as the president of China, the world's biggest polluter, landed in Paris.

The United Nations conference begins at summit level on Monday, when more than 150 heads of state and government – including US President Barack Obama and Chinese President Xi Jinping – will attend talks at a sprawling complex north of the French capital. Xi arrived on Sunday.

To signal determination to resolve the most intractable issues, expert negotiators sat down on Sunday rather than after Monday's high-level speeches, as originally planned.

French Foreign Minister Laurent Fabius said the aim was to give the world the means to cap global warming at 2 degrees Celsius (3.6 degrees Fahrenheit) above pre-industrial times or even 1.5 degrees.

That would avoid the most devastating consequences of global warming, such as rising sea-levels and desertification.

Referring to previous UN conferences that have dragged on days beyond the official close, Fabius said relying on "a last-night miracle" could risk failure. Progress must be made every day.

"The process cannot be chaotic. We owe it to ourselves and to the world to conclude the process in an orderly and respectful manner," he said.

France, as well as hosting the Paris talks, formally takes on leadership of the UN process for a year from Monday.

Governments hope the Paris summit will end on December 11 in a deal that will herald a shift from rising dependence on fossil fuels since the Industrial Revolution to cleaner energies such as wind or solar power.

Hundreds of thousands of people on Sunday joined rallies across the globe, telling leaders gathering for the summit there is "No Planet B" in the fight against global warming.

There is a tough task ahead. Weeks of preparatory talks this year have struggled to whittle down a negotiating text, which is still more than 50 pages long.

The most difficult issues include working out how to share the burden of taking action between rich and poor nations, how to finance the cost of adapting to global warming and the legal format of any final text, as US politicians are likely to block a legally binding treaty.

"Some countries have concerns about all of the targets being binding," Canadian Environment Minister Catherine McKenna told reporters. "The idea is to have a binding agreement. There may be elements that are not binding."

Canada, home to reserves of oil sands, one of the most polluting forms of fossil fuel, withdrew from the 1997 Kyoto Protocol, which any new Paris deal will replace.

It is re-engaging with UN talks following the election of a Liberal government in October.

While big carbon burner China has been reluctant to submit to any outside oversight of its carbon pledges made at a climate summit in Copenhagen six years ago, it has promised to steer its coal-powered economy to a greener path.

The Paris summit is being held in tight security after attacks in Paris by Islamic State two weeks ago that killed 130 people.