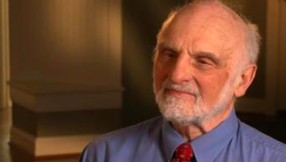

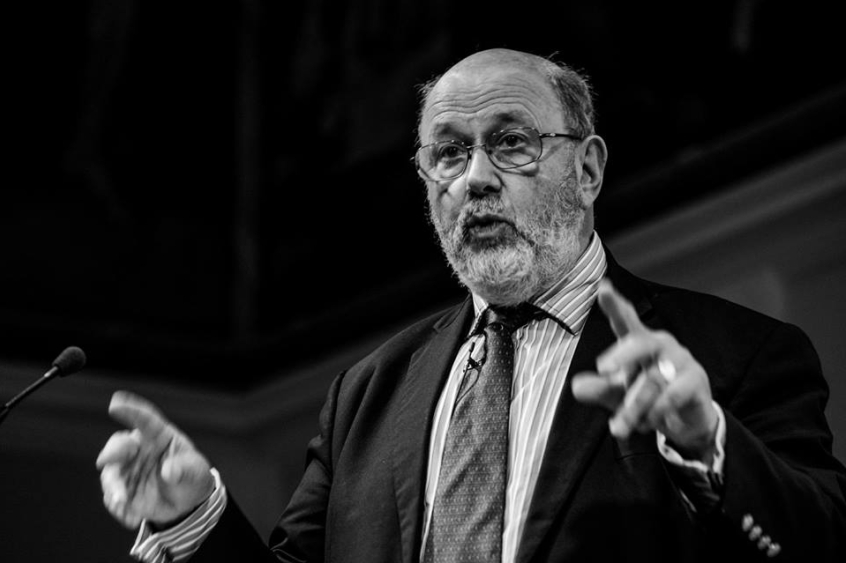

What should the modern world make of St Paul? It's one question the world-leading biblical scholar NT Wright has sought to engage in his latest book Paul: A Biography (SPCK, £19.99).

Wright spoke with Christian Today about why westerners recoil at Paul, why he'd would despair at the church today, and what the 'extremist' apostle had in common with Osama bin Laden.

He's a towering figure in western intellectual history, but the apostle Paul is off-putting to many today both in and outside the church. He was passionate in his beliefs and rarely minced his words in declaring them, even when they made him enemies.

Some want to contrast Paul and Christ – the latter imagined as an inclusive, pastoral preacher of the Kingdom of God, the former austere and aggressive, more interested in sin, doctrine and judgment after death.

Of course, Wright will have none of that – he's spent much of his career as a biblical scholar setting the record straight on Paul. Just see his titani opus Paul and the Faithfulness of God. Now, after friends asked for a take on Paul fit 'for mere mortals' (their words, not his) Wright has completed a biography of the apostle, an engaging 'drama' of his journey from the Christian-persecuting Pharisee to the travelling tentmaker who transformed the church.

Visiting Wright at his academic home at the University of St Andrews, Scotland, I see amid the books and countless academic awards a dramatic artwork showing Paul pitted against the Roman Empire, a piece inspired by Wright's work on the apostle. Paul is 'one of the most formative public intellectuals in history of the world', Wright says, an 'extraordinary' fact given the small corpus of letters he left behind.

Whether we like it or not, Wright says, we are in his debt. Then there's his influence on the church specifically: 'It was Paul who not only taught the beginning generation of the worldwide church what to think but began the process of teaching people how to think, how to think differently in Christ. That's why he says in Romans 12: "Be transformed by the renewing of your minds," that's the challenge. That there is a new way of thinking.'

Then there's another essential element to Paul's work – the Jewish heritage and narrative that undergirds it, but clashes with the painfully pervasive reality of antisemitism today. 'Western culture still hasn't figured out who the Jews are and what we should think about them,' Wright says.

'Even though we know the horrible history of the 20th century particularly, that hasn't made it easier. Paul is right on the cusp of that, as himself a zealous Jew who believes himself to be a fulfilled Jew because he is following Israel's Messiah. What does that mean? So much of the later western tradition has screened out the Jewish bit, and Paul insists that we put it back in. Until we do that, we're not really tracking with the complexity, and hence for Paul the glory, of what he was talking about.'

So what is it about Paul that offends so many moderns today? 'Ever since the civil war in this country and the American Civil War, both countries have had... a horror of zealotry. There's a 16th-century saying: "I'd rather see a regiment of men coming towards me with drawn swords than a lone Calvinist insisting that he was doing God's will."

'In other words, when people get that steely look in their eye, watch out. And so many many people in Britain and America see religious zealotry and they say, "No thanks, we don't like that. It gets us into trouble, we have fights with our neighbours and our friends, we don't want to do that."'

They might see Paul and see an 'out-and-outer': '"We know people like that and they're not much fun to have around" – but actually Paul was fun to have around. He must have been high maintenance as a friend but he was also enormously high value. People knew that he loved them and cared about them.'

Paul was zealous, as Wright emphasises in his book, so does that make him an extremist?

'Oh yes, but then it's one of those flexible words. I'm sure there lots of people who think I'm an extremist, though they probably wouldn't say it to my face.'

Reflecting on religion and society in the early '90s, Wright says: 'Nobody had seen the two 'I''s coming: the Internet and Islamism...two major things which have reshaped the way we think, the way we do everything. We now think of extremism in terms of Islamism. Anyone from a Christian or Jewish view that we call extremist, that's what we think of.'

And, he says: 'In some ways, Osama bin Laden was a public intellectual with a zealous agenda. Paul was a public intellectual with a zealous agenda. It's just that he thought it was all about love and about giving yourself in service, rather than going and killing people. But people hear the extremism and get frightened and think, "No, we want a quiet life."'

So what would this zealot make of the 21st-century church?

'If Paul could come back today and see the contemporary church, I think the thing that would astonish and horrify him would not just be our lack of unity, but the fact that we mostly don't care about our lack of unity. Every letter he writes is about unity.

'Both the Corinthian letters are about, "How do we reconcile, how do we come together in unity, how do we avoid factionalism, how do we avoid party spirit?" etc.

'I think he would say, "OK, you over there, you've done justification by faith, you've actually got it slightly wrong but you've been big on that, fine, but please will you read the rest of the letters where I'm talking about justification by faith, because it's all about unity. And if you think that justification by faith means you have to divide the church and then subdivide it, and then sub-sub-divide it, then something has gone horribly wrong here somewhere."'

He adds: 'Of course, Paul knows perfectly well that unity is not cheap. You can't just say, "Let's just forget our differences and all will be well." Wright says that a focus on unity and holiness, held together, is essential.

'It's easy to be holy if you don't care about unity, you just split off and do your own thing. Until people don't like you, and they split off, and that's the story of the American churches.

'It's easy to be united if you don't care about holiness. Somehow Paul wants to hold onto both and that remains a massive challenge, just as it was in Corinth.'

What does Wright, a former Anglican bishop of Durham, think such a perspective might say to present Anglican debates? Is 'good disagreement' in the quest for unity really possible?

'We have to learn to tell the difference between the differences that make a difference and the differences that don't make a difference,' he says.

When I ask in particular about debates on sexuality, Wright avoids specific theological pronouncements. He says that 'agreeing to disagree' done properly should make demands on people's charity, but never on their conscience. He warns against a dualism that devalues the goodness of creation and a gnosticism that says 'this shabby old body that I have doesn't matter, what matters is the spark of something different which is inside me which tells me who I really am'. He adds: 'We have to remember that the early church didn't make its way in the world by becoming like the world.'

These ethical problems are not simply trivial, he says, but concern what it means to be fully human, living in the light of God's new creation.

'You can't give one line answers to the so-called moral dilemmas of our day, because you need to take several steps back and say that the way the early Christians approached this is so different from how we do moralism in the early 21st century, and if we want to learn wisdom we have to do the hard work of going around that stuff, and not assuming we can either say, "Silly old Paul, we don't need to take him seriously" or "Oh yes, it's in the Bible therefore bang, end of question." It's the Pauline point again: we have to learn not only what to think but how to think.'

Back to Paul. Wright reflects that through his career he has developed 'a certain sixth sense, a certain intimacy' with the apostle, though with millennia between them, mystery remains.

'I'd love to know what he had for breakfast...but we only get little flickers and flashes.' Paul is 'a friend', Wright says, though 'not in the sense that Jesus is a friend, I don't pray to Paul, I don't invoke Paul as I go into a difficult meeting...I thank God for Paul, and I learn from him, but he Is not in that sense a personal presence in the way that Jesus is.'

He's explicit that Paul mustn't be put against Jesus, and that Paul, who had his greatest letter [Romans] delivered, read out and probably expounded by a woman [Phoebe] was certainly not anti-woman.

A few months ago there was something of a high-profile dispute between Wright and another eminent scholar, David Bentley Hart, over the latter's provocative – 'horrifying' in Wright's words – translation of the New Testament. He seems a little disturbed by the reminder, though is also apparently uninvested in the spat, and says he didn't read Bentley Hart's response. 'I do not know what he said, and I do not want to know...Life is short.'

Similarly, Wright stays above the fray when I quiz him on US evangelicals and Donald Trump. Perhaps, like Paul, that's his rigorous resolve at work, undistracted from his call, which clearly for now, is Paul.

He concludes: 'It is extraordinary that even after all the new work on Paul that's been done...the deep-seated English reaction to Paul still remains the same: "He's that 1st-century chap who muddled it all up and shouted at people and didn't like women and so on." You'd have thought that had been disproved...but it's clearly deeply within our culture, and if this book does anything to shift that mood I would be very grateful.'

Paul: A Biography is out now, published by SPCK.

You can follow @JosephHartropp on Twitter