On religious liberty: An open letter to Franklin Graham

This week someone who has put himself forward as a candidate for the presidency of your great nation made a number of hate-filled and inaccurate comments about Muslims, and proposed some extreme policies on the back of those comments. This came to our attention here in the UK because one of the things he claimed, entirely erroneously, was that parts of London were so radicalised that they had become no-go areas for our police and security services.

Our national response was, as our national responses so often are, as mocking as it was derisive. The mayor of London led the way, but on social media many of us joined in with the humour.

I know London well; I trained for ministry there, took my PhD there, pastored my first church there, made, with my wife, our first home there, and saw two of our three daughters come into the world there. My home has been elsewhere for 11 years now, but it is a city I still visit several times a year, a city that still has a significant place in my heart.

For all these reasons, I know that the truth about London was expressed far better by a young Muslim Londoner caught on camera as our police arrested someone who had attempted violence, pretending to represent Islam. In a pure London accent he called out to the attacker, "You ain't no Muslim, bruv!"

London is an exhilarating and sometimes disorientating coming together of people of different national backgrounds and of different faiths; London is also a city that is passionate that people come together, without denying who they are. London Muslims are truly Muslim, and devoted the the peace of the city; London Baptists the same, as I know well. In London, the person who believes the two are impossible to hold together will be told, straightforwardly, "You ain't no Muslim, bruv."

It was with sadness, therefore, that I noticed that you had associated yourself with some of the policy proposals of that presidential candidate, specifically the suggestion that your nation should close its borders to Muslims for an indefinite period. I know that you have spoken strongly about Islam before, calling it a "religion of violence" and so on; I know that your words then were as mistaken as they were inflammatory. I wish that you had taken the time to understand Islam a little before speaking so publicly about it, but I am a Baptist, and so I believe passionately in freedom of speech, even if that speech is damaging and inaccurate.

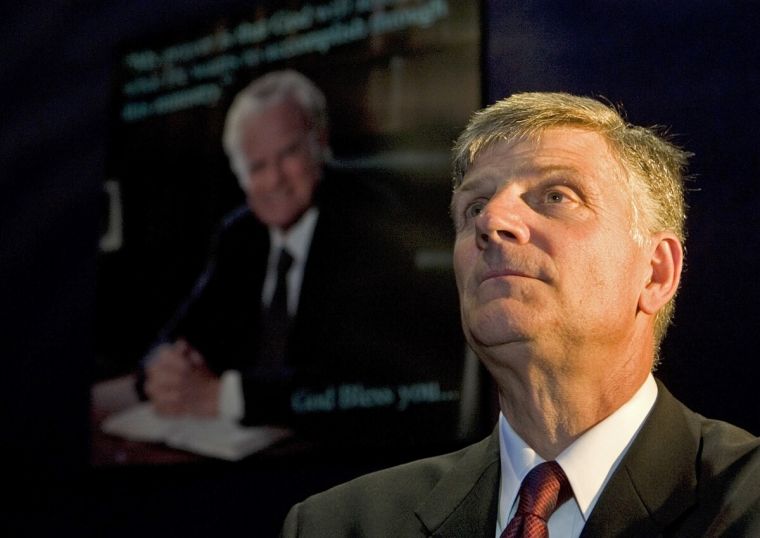

Which is why I am writing to you now, although I do not expect that you will ever read this. Your father is, alongside Martin Luther King, the greatest Baptist statesman your nation has produced; your most recent comments are unacceptable to any Baptist, and – as a Baptist – that concerns me.

Let me take you back to suspicious religious minorities in east London. The attack I referred to above happened in Leytonstone; not far away from there, just the other side of the Olympic Park really, is an older part of London called Spitalfields. There, in 1611, a religious radical suspected of violence and insurrection established a new congregation. His name was Thomas Helwys; his congregation tiny – perhaps in single figures. But that church was the very first Baptist church in England and the origin of the Baptist movement across the world. Your father's faith, and so I suppose yours, can be traced, under God, back to those few believers in Spitalfields.

Helwys was soon imprisoned by the government. The immediate cause of his imprisonment, somewhat ironically, was a book he had written demanding the government grant religious liberty – not only to him and his followers, but to all. As the most famous passage of that book has it, "...man's religion is between God and themselves ... Let them be heretics, Turks [that is, Muslims], Jews, or whatsoever, it does not appertain to the earthly power to punish them in the least measure".

Did you know that the faith of your father virtually began with a plea for religious freedom for Muslims in (what was then) the greatest city in the Western world, Mr Graham?

It is not just Baptist beginnings, either. As your nation began, in the heady days of the revolution, a Baptist, Isaac Backus, was arguing the same point. Backus objected to the newly-independent States imposing compulsory church taxes to support the ministers of the majority, Congregational, churches. In his finest rhetorical flourish, he noted that the tax required of Baptists in Boston was the same as the tax on tea the British crown had so recently required. He was scathing of laws designed to protect (what some regarded as) the truth: "...truth certainly would do well enough if she were once left to shift for herself. She seldom has received, and I fear never will receive, much assistance from the power of great men; to whom she is but rarely known, and more rarely welcomed." From 1611 to 1771, Baptists stood for liberty of conscience, unfettered by the laws of whichever land they found themselves in.

The story continues. The great Edgar Y Mullins, so long the president of Southern Seminary in Louisville, KY, published his greatest work, The Axioms of Religion, in 1908. He changed the language for a new era, speaking of "soul competency", but the doctrine remained: freedom to practise religion is the basic ethical demand of Baptist faith. Today, in your nation, Dr Russell Moore, president of the Southern Baptist Convention's Ethics and Religious Liberty Commission, continues to insist on a belief that freedom of conscience is basic to Baptist public ethics. On the call to close your nation's borders to Muslims, Dr Moore – hardly a liberal – has written: "Anyone who cares an iota about religious liberty should denounce this reckless, demagogic rhetoric."

I do not know if you "care an iota about religious liberty", Mr Graham; I know that you should, and that such care has been at the heart of what it is to be Baptist from a tiny illegal London congregation in 1611 to the upper echelons of the SBC in 2015.

Let me be clear: this is not about any compromise on the truth. Helwys died in prison for his refusal to surrender his Baptist faith; Backus strove mightily to unify the Baptist churches of the new States. Dr Moore wrote in the same piece, "As an evangelical Christian, I could not disagree more strongly with Islam." These are people whose public commitment to the truth of the gospel deserves to be mentioned alongside your father's. Precisely because of their commitment to that truth, precisely because they believed in the present Lordship of Christ, they denied the right of anyone, specifically of any government, to proscribe any form of religious belief. If I may quote Dr Moore's essay one last time, "A government that can shut down mosques simply because they are mosques can shut down Bible studies because they are Bible studies."

Mr Graham, you may feel secure against such persecution because of your friendship with the rich and powerful – or perhaps you cosy up to the rich and powerful when they make vile suggestions like this because you hope to gain enough influence to become secure. We Baptists have learnt down the years never to trust such promises or accommodations. Isaac Backus spoke for us and I remind you of the words: "truth ... seldom has received, and I fear never will receive, much assistance from the power of great men; to whom she is but rarely known, and more rarely welcomed".

Mr Graham, when you have spoken wrongly about Muslims, I have regretted it; when you have unfairly demonised Muslims, I have grieved. Now, however that you propose denying Muslims their God-given right to freedom of conscience, I feel I must, as a Baptist, attempt to call you on it directly. To borrow the words of a Muslim citizen of a city I am proud to have called home, Mr Graham, you ain't no Baptist, bruv.

Dr Steve Holmes is Senior Lecturer in Theology at the University of St Andrews. This piece first appeared on his blog.