One nun's mission to save souls, from death row to the Met opera

With low ticket sales and changing tastes, New York's Metropolitan Opera at times might sound like its future is all too well summed up by its season-opening "Dead Man Walking."

But the new opera by the American composer Jake Heggie, with libretto by Terrence McNally, has been hailed as the first sign of the Met's revival: newer productions pitched to a younger crowd. Fittingly, they've begun with a redemption story, of a nun vying to save a death row convict, first from execution, then from hell.

Opera is full of mayhem, but "Dead Man Walking" delivers it with HBO-like immediacy. The show begins with a violent sexual assault, filmed and depicted on a projected screen, and closes with an execution, clinically and silently. A nurse disinfects the title character's arm with an alcohol wipe, then inserts a needle that injects lethal drugs in a moment both poignant and, by that point in his spiritual and political arc, absurd.

Since Sister Helen Prejean published her 1993 memoir about spiritually advising two death row convicts in Louisiana State Penitentiary in Angola, her story has been adapted into an Oscar-winning film starring Susan Sarandon and Sean Penn, and Prejean has become a leading advocate to abolish capital punishment. After a meeting with Prejean in 2018, Pope Francis announced new language of the Catholic Catechism that unequivocally condemned the death penalty as an attack on the dignity of a person.

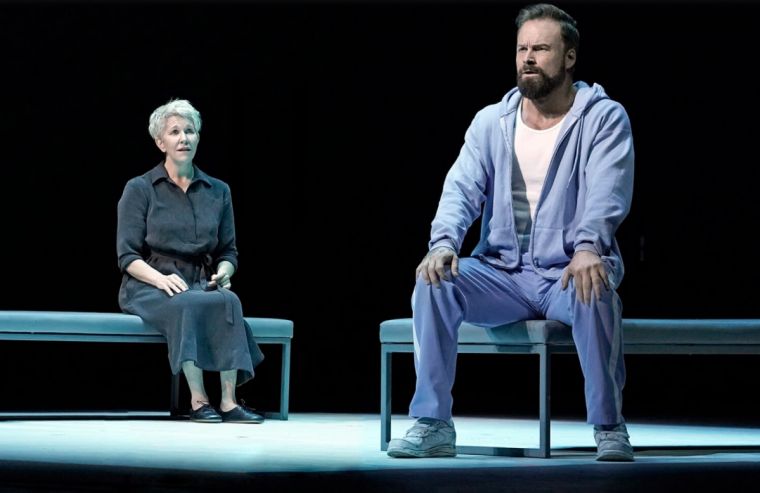

The Met adaptation follows the story of convicted rapist and murderer Joseph (Ryan McKinny), who avoids admitting his crimes until shortly before his execution. Sister Helen (Joyce DiDonato) gently coaxes his confession — "the truth will set you free!" — finally allowing him to receive love and forgiveness from himself, God, Sister Helen and, with luck, the audience.

Heggie wrote "Dead Man Walking" in the late 1990s with the libretto by McNally. It has resonated with audiences worldwide since premiering 23 years ago in San Francisco.

But it has held up well through its various iterations and is as wrenching a story as any Romantic era classic. "It was incredibly powerful and very difficult to watch," said Kathryn Reklis, associate professor of religion and culture at Fordham University, at a panel co-hosted by the Met Opera and the Sheen Center for Thought and Culture in New York on Sept. 25.

The topic has, if anything, become more urgent. Capital punishment is authorized in 27 states and by the federal government for serious offenses. Under the previous presidential administration, federal executions were conducted for the first time in decades. While support for the death penalty has steadily declined since the '90s, a majority of Americans (55%) still favor the death penalty for convicted murderers, according to a 2022 Gallup poll.

Prejean believes most Americans would oppose the death penalty if they knew more about the issue and witnessed state executions. "When I had that experience of being brought to that first execution and here I see before my eyes this man was alive who I had known for two and half years, and I see him being killed ... the first thing I did was throw up," she said on stage at the Sheen Center. "And I remember thinking that people are never going to see this."

Part of Prejean's motivation to write her memoir was to provide an inside look at death row. While her book includes theological and political arguments about the morality of the death penalty, the opera consciously only raises questions — chiefly: Will Joseph's death give the victims' families peace?

Prejean has her own redemption as much as Joseph. In a pivotal courtroom scene, Joseph's mother reads a letter Prejean helped her to write, asking the judge to appeal her son's death sentence. Afterward, parents of the two teen victims ask Prejean why she wasn't there for them. "We are all Catholics! We take the sacraments!" a mother sings defiantly. "It's right or wrong, his side or ours!"

"I made a big mistake in the beginning when I took the first man on death row," said Prejean, recalling the moment the scene is based on during the panel discussion. "I didn't know what to do with the victims' families. I stayed away from them. They were in such pain."

One day a father whose son had been killed approached the nun, saying, "All this time you have been visiting that (convict). We needed you too. Where have you been?" she recalled.

In the opera, she transforms to forgive Joseph, and Joseph transforms to accept his responsibility for his crimes and also forgive himself, offering himself as a sacrifice in hopes that his death will provide peace, though his own mother and younger brothers suffer.

The cast also believes in the power of art, like faith, to change people. DiDonato, who plays Sister Helen, has visited prisoners in Sing Sing since 2015 and prompted Carnegie Hall to bring an abridged version of the opera to the inmates there recently through its music education initiative. Fourteen inmates sang in the chorus with the cast.

Ultimately, the opera alone is not likely to change hearts and minds hellbent on preserving capital punishment. Joseph's crimes are not watered down. But Prejean's redemptive arc shows another path, a messy attempt at becoming God's conduit of unconditional love.

"Even if you're not a person of faith ... it makes you think, what would it mean for me to think about my relationship to other humans and to feel this kind of a demand outside of this other scale of the justice system or punitive right and wrong, guilty or innocent," Reklis said.

© Religion News Service