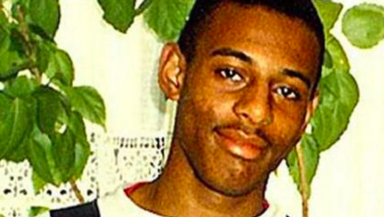

Certain events change society and, as a result, change individual lives. This is certainly true of the tragic murder of Stephen Lawrence on 22 April 1993 and the subsequent Macpherson Inquiry into his death, published in February 1999.

This summer, the House of Commons' Home Affairs Committee published its findings on what progress has been made since the Macpherson report 22 years ago.

Chaired by the formidable Yvette Cooper, the report makes interesting reading of how far (or not so far) the police service and other leading institutions have travelled since Lawrence's death.

Stephen's murder had a profound impact on the police service and other leading institutions in the UK. His death certainly changed the trajectory of my life, as will be illustrated briefly below.

Stephen was 18 when he was killed; he was a promising student who wanted to be an architect. What made his death poignant for me at the time was the fact that I too had a young 18-year-old brother who wanted to be an architect. Stephen was murdered by a group of white racists on Well Hall Road, Eltham, a stone's throw from where I live.

Over the last 22 years, I have come to know his parents, Doreen and Neville Lawrence very well; and I have had the pleasure of working closely with Baroness Lawrence on several Home Office projects and initiatives when I was deputy chairman of the Metropolitan Police Authority (MPA) and a member of the Lawrence Steering Group (LSG), established under Home Secretary Jack Straw in 2001.

I did not know Doreen or Neville Lawrence before their son's death, but I remember spending the first Christmas after Stephen's death with them at a family member's house who was their social worker.

After Stephen's death, I found myself going on marches and protests in support of the family and their struggle to get justice for their son and a public inquiry. I remember taking my five-year-old daughter, Shani, to the plaque marking the spot where Stephen died. I will never forget the expression on her face when I told her that Stephen was killed because he was Black.

Five years after his death, I was approached by a group of senior Black Church leaders to write a Black Church submission to the Macpherson Inquiry and present it at the Tower Hamlet hearing on 15 October 1998. At that time, I was a young academic teaching Caribbean Studies and post-war Black British History at London Metropolitan University.

Within two years of presenting evidence to the Macpherson Inquiry, I was invited to join the Metropolitan Police's Independent Advisory Group (IAG) and appointed by the Home Secretary to the newly established Metropolitan Police Authority. One of the first tasks of the MPA was to agree a compensation settlement for the Lawrence family. Needless to say that my career took an unexpected trajectory, away from the university and into policing and the justice system.

Unsurprisingly, I am intrigued by the Home Affairs Committee's findings 22 years after this defining report.

The written and verbal evidence presented to the Home Affairs Committee make interesting reading, not least that given by the Metropolitan Police Commissioner, Dame Cressida Dick, and the Black Police Association (BPA).

According to the BPA, progress has been "extremely slow", their members have experienced hostility, and BAME officers have been arrested "for offences which do not exist". The Commissioner put up a robust defence of her officers and questions the current efficacy of the Macpherson definition of 'institutional racism' - "The collective failure of an organisation to provide an appropriate and professional service to people because of their colour, culture or ethnic origin. It can be seen or detected in processes, attitudes and behaviour which amount to discrimination through unwitting prejudice, ignorance, thoughtlessness and racial stereotyping."

The Commissioner told the Committee that this definition "is not helpful".

One will recall that at the time of the Macpherson Inquiry, the Police Commissioner, Sir Paul Condon, came under heavy criticism for the behaviour of his officers. Macpherson's conclusion was devastating: "The investigation was marred by a combination of professional incompetence, institutional racism, and a failure of leadership by senior officers (p.317)."

So where are we now after the publication of the 'pink report' that was hailed as a defining moment in Britain's race relations? Of course, we are not where we were over two decades ago.

This was recognized by the Home Affairs Committee. The report rightly indicates that Macpherson "led to major changes in attitudes towards racism and to progress on race equality both in policing and across society."

However, it also candidly acknowledged that "the early momentum was not sustained, and persistent problems were not addressed."

According to the report, there is a "new focus" on challenging racism in a "sustained and determined" manner. And this is not only in all policing institutions and government, but also in the wider society.

Macpherson made 70 recommendations across 13 themes, including family liaison, stop and search, training and valuing diversity, and recruitment and retention of minority ethnic officers.

Many of the 70 recommendations have been implemented by the police service; other public institutions have also used them to inform and shape their policies, practices, and procedures. In education, there have been significant strides to keep faith with Recommendation 67, which called for amending the National Curriculum in schools aimed at "valuing cultural diversity and preventing racism, in order better to reflect the needs of a diverse society".

Over the last two decades, the Lawrences have spent a lot of time in schools and colleges speaking to students and young people about leadership, aspirations and citizenship. Indeed, the Stephen Lawrence Charitable Trust has been instrumental in providing bursaries, work experience, and placements for young aspiring architects.

Twenty-two years ago, the previous Police Commissioner of the Metropolitan Police admitted: "I believe that the way the police meet the needs of minority ethnic communities in terms of their experience of crime and harassment is of such importance that a priority is needed in order to achieve lasting change. It has become increasingly clear that nothing short of a major overhaul is required." (Macpherson, Sect.46.41)

But to what extent has Sir Paul's call for a "major overhaul" taken place in the 43 police forces in England and Wales? Has there been progress in ensuring that Black, Asian, and other minority ethnic officers and staff are properly represented at all ranks of policing? What is the current state of police relations with BAME individuals and communities?

Notwithstanding the thorny question about whether the MPS is still 'institutionally racist', these are some of the key questions the Committee sought to address. Its conclusions are both instructive and salutary. For anti-racism campaigners it makes depressing reading.

Twenty-two years after Macpherson, it concludes: "Our inquiry has found that the Macpherson report's overall aim of the elimination of racist prejudice and disadvantage and the demonstration of fairness in all aspects of policing has still not been met twenty-two years on, and we have identified areas where too little progress has been made because of a lack of focus and accountability on issues of race."

I am, of course, saddened by the lack of progress identified by the Home Affairs Committee, but I remain encouraged by some of the good practices I see in the Met (e.g. IAGs, community engagement, and family liaison) and the courage and professionalism of Black, Asian, and minority ethnic officers who have made the police service their employer of choice because they want to make a difference to the service and to their communities.

I end by paying special tribute to Baroness Doreen Lawrence and Neville Lawrence for their faith and courage in the long struggle for justice for their beloved son Stephen.

In her 2006 book 'And Still I Rise: Seeking Justice for Stephen', Doreen said that she tries to feel positive about the changes that have been brought about as a result of Stephen's death—new laws, training for the police, and an understanding of the nature of 'institutional racism'. Stephen Lawrence Day is now commemorated on 22 April. For this, and the many changes Stephen's death has brought about in our public institutions and in our political consciousness, we owe Doreen Lawrence a debt of gratitude.

Dr R David Muir is Head of Whitelands College, University of Roehampton, and Senior Lecturer in Public Theology & Community Engagement. He is the Director of the Centre for Pentecostalism & Community Engagement at Roehampton University and executive member of the Transatlantic Roundtable on Religion and Race (TRRR). In 2015, he co-authored the first Black Church political manifesto, produced by the National Church Leaders Forum (NCLF).