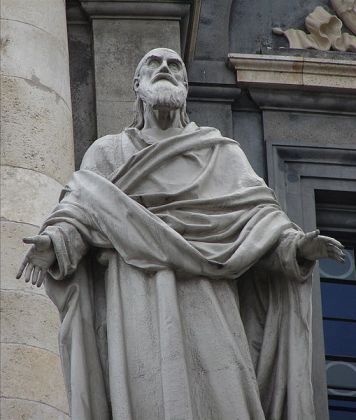

Polycarp, the bishop who was grateful to be a martyr

Polycarp – whose name means 'much fruit' – was born in Smyrna, today's port of Izmir in Turkey. He was born in AD 69 and grew up at a time when some of those who had seen and heard Jesus were still alive. Converted at an early age he knew the apostle John, who in old age lived not far away from Smyrna in Ephesus.

Throughout his long life, Polycarp was able to recount what he had heard from John and others who had been with Jesus. Living on to the middle of the second century, he became known as the last living link with the apostles.

Polycarp became a church leader and eventually bishop of the Smyrna region. These were challenging times for the infant church; not only did it face growing persecution but, as the memory of the first disciples faded, differences and divisions were emerging over beliefs, practices and which documents were to be considered authoritative. Polycarp, with his friendship with the apostle John, played a vital role in keeping the church on course; identifying which letters were to be considered authentic.

He was also a bridge builder. When practical differences arose between the churches in Asia Minor and those in Rome over such things as when Easter was to be celebrated, Polycarp went to Rome to work out a solution.

Yet if he laboured for church unity, Polycarp was also a man who was unafraid of firmly opposing anything or anybody that was a threat to the true faith.

Polycarp wrote letters and is one of the earliest Christians, other than the authors of the New Testament, whose writings have been preserved. Only one work has survived: the Epistle to the Philippians, a pastoral letter that addresses church problems.

In it Polycarp gives a hundred quotations from the gospels and letters of the New Testament and, in doing so, demonstrates that much of the New Testament was already considered authoritative by the second century.

Polycarp's influence arises from his death, recorded in the Martyrdom of Polycarp. When he was in old age, the Roman authorities wanted to arrest him. Polycarp was persuaded to take shelter in a farm where he spent days in prayer for people and for churches. When he was finally discovered and the authorities arrived to arrest him, Polycarp treated his captors with gentleness, offering them food and drink. He asked for an hour to pray but prayed aloud for two hours with such grace that many of those who had come to arrest him found themselves regretting their task.

Polycarp was taken to the amphitheatre. There, the proconsul – clearly unhappy about executing a very old man – tried to persuade Polycarp to deny his faith, reminding him that all he had to do for his freedom was to offer a small sacrifice of incense to Caesar and reject Christ. Polycarp's defiant answer has rung down through the centuries: 'Eighty-six years I have served him, and he has never done me any wrong. How can I blaspheme my king who saved me?'

The proconsul made further threats to try to persuade him to yield. The bishop, however, seems to have given as good as he got and when threatened with being burnt to death gave a pointed response: 'You threaten me with a fire which burns for an hour and is then extinguished, but you know nothing of the fire of the coming judgement and eternal punishment, reserved for the ungodly.'

In the end the proconsul decided that execution was the only option and the bishop was taken to the stake. There, Polycarp gave a prayer of thanks that he was counted worthy of being a martyr and offered praise to God. The fire was lit and when, strangely, it failed to burn him, Polycarp was stabbed to death with a dagger.

Let me point out three striking things about Bishop Polycarp.

First, Polycarp had an outstanding life. When he was arrested Polycarp was in his late eighties and was felt to be sufficiently important to be worth arrest and execution. Had he been retired, inactive and inoffensive the authorities would surely have simply ignored him and let age and infirmity do the job for them.

The fact is that, despite his great age, Polycarp was clearly still an important church leader. I'm reminded of Psalm 92:14 which, referring to 'the godly', promises, 'Even in old age they will still produce fruit; they will remain vital and green' (NLT). There is a tremendous encouragement here for anybody heading into, or already in, 'senior years'. Only God ends a Christian ministry.

Second, Polycarp had an outstanding death. In his martyrdom we see a courageous submission to God's will, a defiant refusal to compromise and, above all, a radiant acceptance of death. His martyrdom is a reminder that to be a Christian may involve the highest of costs.

Finally, Polycarp had an outstanding influence after his death. He is one of many Christian heroes who made a greater impact after their death than in their life. An account of Polycarp's death was immediately written down and circulated throughout the church. It proved to be a tremendous encouragement to those facing persecution under Rome and has been an inspiration to suffering Christians across the world ever since. Polycarp, true to his name, did indeed bear 'much fruit'. May we do the same!

Canon J.John is the Director of Philo Trust. Visit his website at www.canonjjohn.com or follow him on Facebook, Instagram or Twitter.