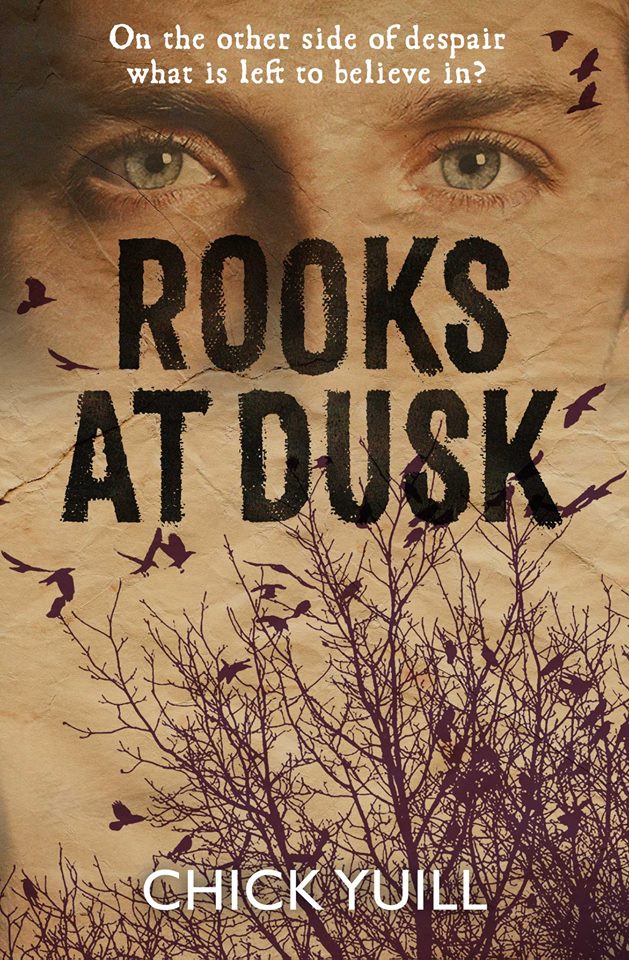

Rooks at Dusk: Why I use fiction to spread the gospel beyond the Christian sub-culture

Our 21st century British culture has a confused and confusing attitude to matters of faith. Never has that been more clearly demonstrated than by recent events.

On the one hand, a major political figure (Tim Farron) feels forced to resign from the leadership of his party because most of the press and many of the public seem to be deeply suspicious of his Christian faith to the point where they believe that it renders him unable to make objective decisions or function effectively in a liberal democracy.

On the other, confronted with the recent terrorist atrocities in Manchester and London, millions have faced the destructive power of evil and defiantly repeated the mantra that 'love is stronger than hate'. A moment's reflection is enough to reveal that such a statement goes far beyond cold rationality. It is surely the ultimate statement of faith – a bold assertion that life is not merely at the mercy of blind chance or competing powerful forces, and that goodness and love will ultimately prevail.

Those are just a couple of examples of the maze of contradictions that surround the subject of faith in Britain today. The challenge for those of us who declare ourselves to be followers of Jesus is how we negotiate our way through that maze in such a way as to disarm suspicion, discern people's genuine experiences of God, and point them in the direction of an authentic encounter with the living Jesus.

Some would argue that all we need to do is to declare biblical truth clearly and equip Christians with the skills of personal evangelism that will enable them to share their faith boldly and effectively. But my growing sense is that, vital as those things are, there is other work to be done to prepare the soil if we want to see the seed of the gospel sprout into life in our culture and in our lifetime.

If you want scriptural warrant for the approach for which I'm arguing, then I need do no more than cite Paul's strategy when he addressed the people of Athens, having seen their statue to 'the unknown god'. Far from being confrontational or condemnatory in his approach, he makes reference to their religious practices and quotes approvingly from their poets (Acts 17:16-34). In effect, he was 'tuning into' their culture – with all its confused understanding of what faith means – in order to prepare their minds and hearts to receive his message.

Of late, this has become a matter of more than passing interest to me. Over the last 30 years I've spoken at Christian conferences, regularly contributed to Pause for Thought on Radio 2 and written a number of books explicitly aimed at the 'Christian market' on such topics as discipleship, grace and holiness. I hope and pray that they have been of some help to readers. But increasingly I've had a deepening conviction that I need to play my small part in bringing matters of faith out of the narrow confines of the Christian sub-culture and into the wider arena of public life and discourse. For me that means using whatever skills I possess as a writer to tell a good story that deals with real-life issues and invites the reader to reflect on what they have read and make up their minds as to where the truth is leading them. After all, that's what Jesus did. So I know I'm in good company.

Rooks at Dusk is my first novel. It tells the story of Ray Young, an experienced Christian leader who suffers a moral and emotional collapse, and his son, Ollie, a stand-up comic who has rejected his parents' faith from his teenage years. Their already strained relationship reaches breaking point when Ray confesses his adultery to his son. And when tragedy strikes before Ray can begin to put things right with his wife it seems there is no hope of redemption or forgiveness. As the narrative unfolds he faces the question, 'Where can a man find grace and reconciliation when he can no longer believe?'

The feedback from readers has been encouraging beyond my expectations. Many of these early readers are Christians who have expressed appreciation for what they have generously described as a well-told tale in which the fragility of faith and the reality of doubt is acknowledged and glib answers are avoided. That resonates with their experience far more, they tell me, than what they have found in too much 'Christian fiction'. To my delight, the book has also found its way into the hands of of readers who have no commitment to the Christian faith – Muslims from the Indian sub-continent, neighbours from communist mainland China, self-confessed atheists. Their reaction can be summed up in four brief sentences: 'I loved the story. It wasn't too religious. It made me think. When are you going to write the next one?'

That's enough to encourage my growing belief that fiction is a great way of touching truth and reaching hearts and minds in a way nothing else can do. So for my next novel...

Chick Yuill is a speaker and writer.