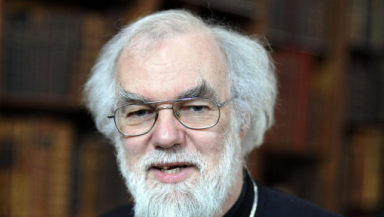

The former Archbishop of Canterbury has said that fears surrounding teachers wearing the Muslim face veil are "largely misplaced".

In an interview about language and the way we talk about God, Rowan Williams said that language does not operate in a straightforward manner, but is instead embodied in practice. What you say is just as important as how and where you say it, in addition to your physical presence.

"Language is, after all, a way of interacting with the environment, not just a labelling process which would have no connection at all with the business of finding your way around," Williams told Christian think-tank Theos' Nick Spencer.

"As I learn a language, I learn not only to identify objects, I learn how to interact with another speaker."

Williams therefore drew the conclusion that allowing teachers to wear the niqab has led to some anxiety as parents are afraid that key elements of interaction with pupils will be lost.

"I suppose that's what panics people about, let's say, a primary school teacher wearing the face veil," he explained.

"As a matter of fact I think that's a largely misplaced anxiety, but I can see where it comes from. I've actually been in public discussions in Pakistan with women wearing full face veil, and you learn to read differently, it's not that those codes don't happen...but there's a cultural obstacle to overcome."

Sarah Ager, interfaith activist and curator of Interfaith Ramadan, told Christian Today that the former Archbishop's comments could go some way to humanising the issue, which she says is "crucial" in the debate.

"Admittedly, the issue of niqab in schools is a complex issue and, as Rowan Williams says, there are understandable concerns. This issue however is has become highly politicised in recent years, and although there are many secularists and members of the public, and even Muslims themselves, who have genuine concerns over niqab as a religious symbol in schools, the issue is too often used as a tool by those with an Islamophobic agenda or by the media as a means of creating fear of an 'other'," she said.

"The former Archbishop's words are very welcome because they acknowledge cultural difference and show that the niqab itself is not a barrier to communication or education, although as he admits, it may take a bit of getting used to. His words humanise those wearing niqab and this is crucial to interfaith dialogue. Without reaching out and getting to know members of other faiths as individuals, on a human level, and making interpersonal connections, interfaith dialogue is just a lot of pie in the sky ideas."

Ager said it is imperative to balance the freedom of belief with removing religious privilege. "Niqab, and those who wear it, find themselves on the faultline of these opposing views. However, underneath all the abstract theory, ideology and politics, it's easy to forget the women directly affected by the consequences of this debate," she explained.

"These are women who are spoken about but who are very rarely spoken to on this issue. The banning of niqab would marginalise a small group of women who are already in the minority, both as Muslims (only 5 per cent of the population) and even more so as niqab wearers. It corners them into the uncomfortable position of choosing between faith and vocation. It would affect them economically, effectively taking away their living. Moreover, the education system (and by extension the students themselves) would lose these teachers' invaluable experience and skills as a result."