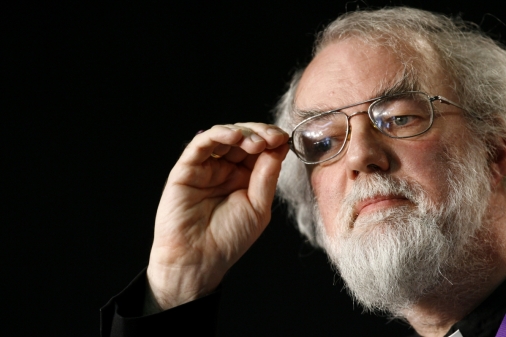

I thought for literally half a second that I'd met the girl of my dreams. Sitting on my own in a restaurant with Rowan Williams' new book, Being Disciples: Essentials of Christian Life, an observant waitress exclaimed: "I love Rowan Williams!" Our eyes met. "Have you seen Blackadder?"

Williams himself, though not a professional television comedian, by all accounts has a very well developed sense of humour and would be the first to see the funny side of the awkward moment. Not least because of the cliché that has him as a remote, inaccessible figure.

He is, in fact, very far from that. So who, then, is Rowan Williams?

We know that he's probably the world's leading living theologian. We know he's the former Archbishop of Canterbury, who prayerfully and at times painfully steered his Church through the perennial and often distracting trials over sexuality inflicted by extremists on both sides. We can guess from a distance that he is now likely, thankfully, to be in better spirits, having returned to academia from whence he came. And we now know, thanks to a series of books published since he left Lambeth Palace, that, contrary to myth, he is highly accessible as an author.

We'll explore lightly Being Disciples, which follows Being Christian and Meeting God in Mark (2014) and Meeting God in Paul (2015), all published by SPCK. But first, a true glimpse of Williams given by one close colleague from a 2008 profile of the then Archbishop.

"People who have met, spent time with, listened to, worked with or who know Rowan...will tell you that he is a remarkable man...It is not just that he is the most prodigiously intellectually gifted person almost any of us will have ever met, or will ever meet, and one of the most self-disciplined – in a monastic sense – of people in respect of the daily practice of the virtues and time spent [every day without exception] in prayer – all of which is remarkable enough – it's that he applies all the extravagant gifts he's been given in love and service. He's on the job [of being a disciple] all day every day where most of us flit in and out. This is a man who really has glimpsed what it means to live sacrificially, non-judgementally, honestly, generously, truthfully, in touch in a deep way with the wisdom of God. Rowan is uncommon. If only we could just get used to that and enjoy the good news that he's here, he's real, and he's Anglican."

Indeed, as Eleanor Mumford, co-founder of Vineyard Churches in the UK, has said of Being Disciples, "This gem of a book is clearly born of the author's own deep love of Jesus". In the short book, based on a series of talks from 2007 to 2012 and tagged with brief discussion points at the end of each chapter, Williams shares his insight into what it's like to be a disciple, with reflections on faith, hope, love, forgiveness and more.

It is, above all, truly authentic. He talks and explores from experience. So when, for example, the author takes up the bird-watching metaphor for prayer, you believe that he really does have moments when he sees what TS Elliot called 'the king-fisher's wing' flashing 'light to light'. Because as Williams says, "The experienced birdwatcher, sitting still, poised, alert, not tense or fussy, knows that this is the kind of place where something extraordinary suddenly bursts into view." You can imagine that unlike most of us, Williams does indeed sit still for long enough, waiting with his Master, to gain that different perspective, that new light.

The main achievement of this book is of course, as with Mark and Paul, to provide unique insight into Jesus Christ, to lead the way to Jesus, to unveil Jesus's true identity. But a doubtless unwanted side effect given by this extremely modest author is to give a further glimpse of Williams the disciple himself.

So when Williams, in his first chapter talks about each person as a gift, you believe that this is how he approaches meeting other individuals. "[It] can't be said too often that the first thing we ought to think of when in the presence of another Christian individual or Christian community is: what is Christ giving me through this person, this group?...[You] begin by asking, 'What is Jesus Christ giving me here and now?' Never mind the politics, the hidden agenda, or anything else of that kind, just ask the question and it will move you forward a tiny bit in discipleship."

Later, in a chapter on the meaning of holiness in which Williams characteristically explodes conventional wisdom – gently demolishing the idea that to be holy is necessarily to be good or apparently "saintly" or pious or "nice" – again you receive extraordinary insight into the writer. In one of his most personal passages ever published, Williams describes how holy people "make you feel better than you are...the holy person somehow enlarges your world, makes you feel more yourself, opens you up, affirms you." He goes on: "When I think of people in my own life that I call holy, who have really made an impact...[these] people have made me feel better rather than worse about myself. Or rather, not quite that: these are never people who make me feel complacent about myself, far from it; they make me feel that there is hope for my confused and compromised humanity...somehow, I feel a little bit more myself...I have a theory, which I started elaborating after I had met Archbishop Desmond Tutu a few times, that there are two kinds of egotists in this world. There are egotists that are so in love with themselves that they have no room for anybody else, and there are egotists that are so in love with themselves that they make it possible for everybody else to be in love with themselves...And in that sense Desmond Tutu manifestly loves being Desmond Tutu; there's no doubt about that. But the effect of that is not to make me feel frozen or shrunk; it makes me feel that just possibly, by God's infinite grace, I could one day love being Rowan Williams in the way that Desmond Tutu loves being Desmond Tutu."

Of course, Williams – who begins each chapter with a passage from the New Testament – goes on to focus on Christ. "This is why we say of Jesus that he is 'the most Holy one,' because he above all changes the landscape, casts a new light on everything." Throughout, he is redirecting our attention onto what matters. We have Williams the linguist and classicist's trademark love of words, and their original and truer meanings. An example comes at the start of the book when he introduces discipleship as the concept of staying (such as in John 15), or abiding. And later, in Life in the Spirit, in a passage that should make all modern Christians think, he begins "by being a bit rude about the word 'spirituality'": it is helpful shorthand, he says, "but we ought to be aware of just what an odd turn of phrase it is. Spirituality is really quite a modern word. If you had asked anybody in the fifteenth or sixteenth century, 'Tell me about your spirituality,' they would not have had a clue what you were talking about." Williams goes on to revert to Paul's meaning of 'life in the spirit' and the practical fruits of that life: love, joy, peace, patience, kindness, goodness, faithfulness, gentleness and self-control. "And whenever we're tempted to think that spirituality is something a bit remote and specialized, or rather exotic and exciting, in the corner or our lives, we ought just to say to ourselves in a mantra-like way: love, joy, peace, patience...bog standard human goodness."

But the irony of this, and the Tutu point on holiness, is not lost on anyone who has met Williams himself. For contrary to conventional wisdom, there is nothing remote or exotic about Williams' own real and practical holiness. Throughout the book, a characteristic theme is that we should be led by Jesus to people with whom He is: the waifs and strays, the inadequate, the poor, the sick, those on the margins of society, those with no economic value, the mentally ill. And by all accounts, this is something Williams actually puts into practice.

There are other classic Williamsisms in Being Disciples: in stark contrast to other church leaders, he once said: "What I'm deeply uncomfortable with, I think, is saying things that really don't change anything, that don't move things on...I am very worried about the morality of simply sounding off". And in the book, there is an amusing, bracketed aside in a beautiful passage on silence in the chapter Life in the Spirit: "Silence of word, stillness of body. And silence of word, of course, doesn't just mean not saying anything (although that is always quite a good idea!); it can mean finding ways of saying, ways of speaking, that settle and still you: the small phrase, repeated, that does not break the silence. Like waves on the beach on a calm day; just the beat of a heart; small words, small phrases that keep us steady and hold us when everything else is pushing us around."

Williams' ultra-liberal critics meanwhile won't be surprised by the (consistently) traditionalist – conventional – positions he takes on the secularisation of society and on marriage, family, and sex.

On the other hand, he appears subtly, implicitly, to consider the radical and unconventional idea of disestablishment, in his chapter on 'Faith in society': "The Christian vision is not...one in which the person's choice is overridden by a religiously backed public authority. History tells us that when churches try directly to exercise political authority they often compromise their real character as communities of free mutual giving and service; equally, when they retreat in the face of power, they risk betraying their Christian distinctiveness...A healthy democracy, then, is one in which the state listens to the voices of moral vision that spring from communities that do not depend on the state itself for their integrity and meaning."

Holy, spiritual in the true sense, unpushy, independent-minded, at once conventional and unconventional. Accidentally, this authentic little book tells us not just about the meaning of discipleship, but also a little more about the disciple himself.