Scientists explore edge of universe, finding bursting galaxy at record-breaking distance of 13.4 billion light-years from Earth

Space scientists are discovering more and more things about the universe as they explore the farthest corner of the cosmos that can be glimpsed by man billions of light years away from Earth.

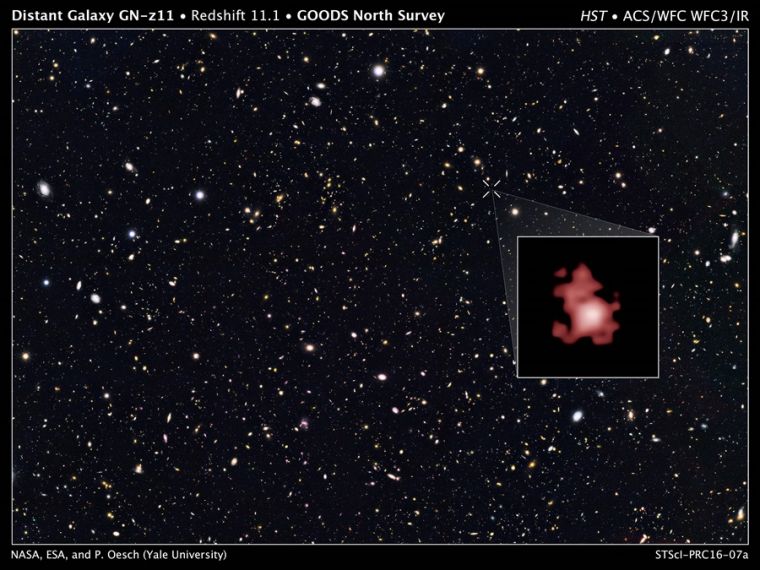

A team of astronomers recently spotted a hot, star-popping galaxy from a distance never explored before: 13.4 billion light-years. Each light year is equivalent to about 5.8 trillion miles.

This discovery, accomplished with the use of the Hubble Space Telescope, shattered all previous records in terms of distance, and may be difficult to beat any time soon, unless a new and more advanced device is developed.

The galaxy, named GN-z11, also breaks the records in terms of time, being from a period when the Earth was only 400 million years old.

Gabriel Brammer, an astronomer at the Space Telescope Science Institute and co-author of the study, explained that while the telescope captured a photo of the faraway galaxy where it appears darkish red, it is actually bright blue, indicating that it is very, very hot.

"It really is star bursting," Brammer said, as quoted by Fox News. "We're getting closer and closer to when we think the first stars formed ... There's not a lot of actual time between this galaxy and the Big Bang."

The astronomer further explained that if the galaxy was only a stone's throw away from Earth, it will appear "blue, stunning, really bright young stars."

He added that the galaxy will manifest itself as "very messy-looking objects," which means that it is still forming. More commonly, galaxies like our own Milky Way Galaxy appear to be spiral when fully formed.

Competing astronomer Richard Ellis at the European Southern Observatory, however, was doubtful about this discovery. He explained that for it to be spotted, GN-z11 would have to be three times brighter than typical galaxies.

Pascal Oesch of Yale University, the study's lead author, assured that his team made sure that their observations and computations were "as clean as possible."

Despite some doubts on this discovery, independent astronomer Dimitar Sasselov from the Harvard University, highlighted the significance of this study, which was published in the Astrophysical Journal.

"Seeing and understanding the first galaxies and the first stars is an essential part of our origins story," Sasselov told Fox News.