When we talk of nuclear technology, most people usually associate it to destructive warfare. The atomic bombings in Japan that killed over 129,000 people, and the debate on what to do with the nuclear weapons programmes in Iran and North Korea contribute to the negative perception about this technology.

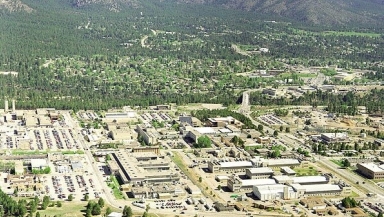

In the highly secure Los Alamos National Laboratory in northern New Mexico, however, nuclear technology is being tapped for a very noble cause: to find a cure for cancer.

Physicist Eva Birnbaum is leading experiments in this laboratory, where scientists built atomic bombs some 70 years ago, to use radioactive elements to battle cancer.

Birnbaum is particular working with the new cancer-treating agent, actinium 225 or ac-225.

This anti-cancer agent is proving to be a potent and unique cure because the alpha particles it emits are quite feeble, so it does not hurt healthy tissues or cause damage past the targeted area during treatment.

"I think we're very hopeful that this will have tremendous impact for some cancers right now that really don't have highly effective treatments," Birnbaum told NBC News, which gained access to the nuclear laboratory.

In addition to these, alpha particles emitted by ac-225 have a half-life of 10 days, meaning half of it is gone after 10 days and does not remain in the body's systems for a long time.

Based on early clinical trials, the ac-225 can be used to effectively cure leukaemia, melanoma, and cancers of the prostate and breast.

The problem, however, is that the supply of this cancer-treating agent is quite low, supposedly insufficient even for clinical trials.

Because ac-225 is also difficult to produce, scientists at the Los Alamos National Laboratory are toying with the idea of using particle accelerators, which have been used in the past to create nuclear weapons, to make ac-225 from another radioactive element called thorium.

"This project is aimed at making 50 times more material available than is available right now," the laboratory's project manager, Kevin John, explained.