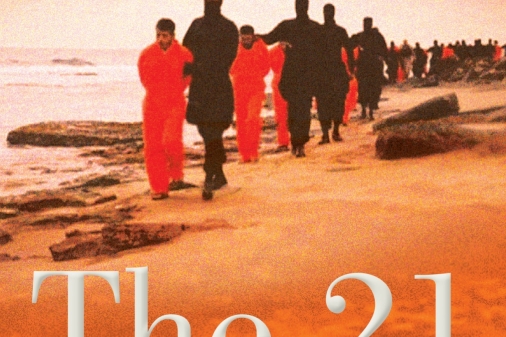

Exactly four years ago, on a beach in Libya on February 15, 2015, 21 orange-clad men were beheaded by fighters of Islamic State.

The actual moment of death is missing from the video, perhaps because it is too amateurish and messy to fit the careful choreography of the atrocity. But it's still a moment that made it utterly clear to the world that this was an evil with which there could be no compromise.

Twenty of the men were Coptic Christians from Egypt, all from the same small area and identifiable by the small crosses tattooed at the base of their thumbs. The 21st, Matthew, was from West Africa, perhaps Ghana. No tattoo for him, and his captors are said to have told him to go. However, he said 'I am a Christian' and chose to share the others' fate. Like them, his demeanour facing death was extraordinarily peaceful. It is this evident willingness to die, with the last whisper of 'Ya Rabbi Yassou!' – 'O my Lord Jesus!' that has led to them being hailed as martyrs by the Coptic Church.

Their story is told in a fine account by novelist Martin Mosebach, whose book The 21: A Journey into the Land of the Coptic Martyrs is an extraordinary exploration of the spirituality that allowed these 'ordinary men' – and this ordinariness is a recurring theme in the book – to rise to such a height.

In February 2017, Mosebach travelled to Upper Egypt to meet the families of the 21 and other people who knew them. Apart from Matthew, they were Coptic migrant workers from Egypt, who came from poor farming families and had travelled to Libya to find better paid work. In Libya, they had been sleeping side by side on the floor in a large room, so they could save more money to send home to their families. Some of them could read but probably not write – others were illiterate.

Mosebach explores their lives and homes, and the landscape of their faith. Their black and white passport photographs punctuate the pages. He paints a picture of a people who for the last 1,400 years, since the Arab Muslim invasion, have been a minority, often oppressed and downtrodden. But their outsider status has helped preserve their greatest treasure: their Christian faith, which also preserves them in the face of all their trials.

This faith is profound and personal, and not only among 'professional' Christians, the priests and monks. Back to 'ordinariness': Mosebach interviews a bishop who asks him why he is so curious about the martyrs. 'This is not a Western church in a Western society. We are the Church of Martyrs. I take no special risk when I say that not a single Copt in Upper Egypt would betray the faith.'

As Mosebach says: 'Well, if they were indeed your average young men, then the bar for what was average had been set pretty high.'

And this from a young woman: 'They were ready to die, and even longed to. We all do! We're all ready and yearning because we all want to vouch for Christ.'

Mosebach's journey, as a German traditional Roman Catholic into the faith that could make martydom routine, is fascinating; he has long been interested in Oriental Christianity. Roman Catholicism, he tells Christian Today, is in a 'deep crisis'. 'There is a complete incapacity to find a real religious language; it is shrinking, losing influence.' In this 'martyrdom of illiterate young people', he says, we are reminded that 'the real essential of Christianity is not to talk about the problems of the world, but to witness to the resurrection'.

'I found that seeing real martyrs is much more important than what any pope or bishop or theologian may quote or say in everyday media,' he says. 'It was a return for me to the real important thing.'

Reflecting on the young girl who said she was ready to die for her faith, he suggests Coptic Christians may have a different concept of 'truth'. 'In the Western world we have had a particular problem in the last 200 years with the word "truth". It's something embarrassing. We are sceptical, we doubt and we think there are so many kinds of truth, and what is for one person the truth is for the next a lie, or meaningless, or that every age has its own truth. But Jesus said, he is the truth. The words of Jesus are big rocks on the way of our thinking. You cannot diminish them.'

The Coptic Church – with its 1,400-year history unruptured by Reformations and schisms – has preserved this notion of truth unsullied. Even its liturgy is mainly musical and visual: it has no place for the argumentative and intellectual sermon that characterises Western devotion. Consequently, says Mosebach, Coptic Christianity is a spiritual time capsule, which has preserved for the Western church an image of the early church. The martyrdoms under the Emperor Diocletian and the martyrdoms on that beach in Libya are not different in kind: Copts know how to die, because they remember. As Mosebach says in his book: 'In their isolation, the Copts of Upper Egypt experience the events of the early church as if they had only happened yesterday, and this helps them preserve the simple core of the Christian message.'

What is the future for Copts in Egypt? There are regular outbreaks of violence against them. Many are very poor. They are used to being marginalised; the Egyptian government will not even count them, because there are probably more of them than they think. His last interlocutor, a hotelier, asked what can be learned from all this, says: 'Whatever you do, don't belong to a minority! That's what can be learned!'

But Copts are used to being a minority, and they are not going anywhere.

Mosebach has a novelist's insight and way with words. The 21, his first major non-fiction work, is also a fine piece of journalism. It helps us to understand, if not the ferocity of the killers, the quiet heroism – the ordinary heroism, perhaps – of the martyrs.

And as he says, reflecting on the explosive mood of Egypt today: 'Meanwhile, simply by renouncing revenge and retribution, the invisible army of martyrs grows, ever greater and ever more powerful.'

'The 21: A Journey into the Land of the Coptic Martyrs' is published in the UK by Plough Publishing, £18.99.

Follow Mark Woods on Twitter: @RevMarkWoods