Christian Today's contributors and advisers share their favourite books from the last year and why you should be sure to give them a read.

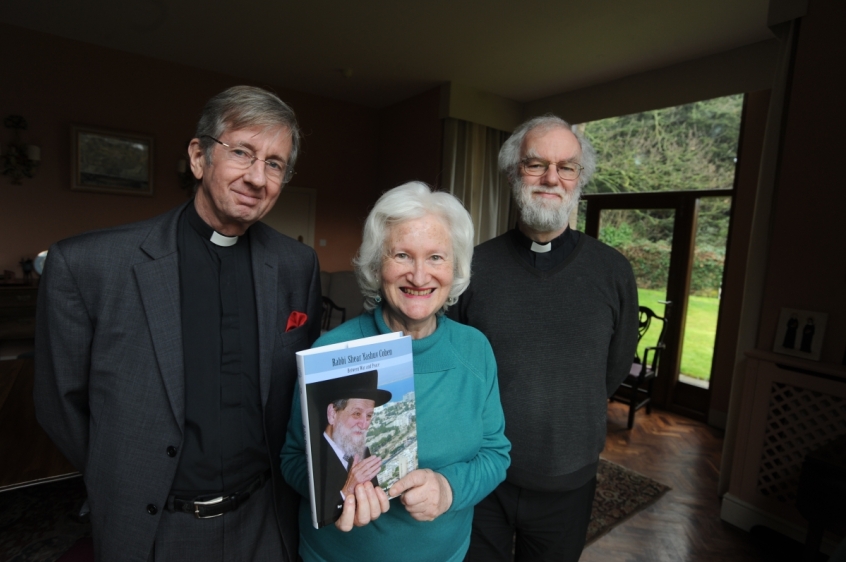

Dr Rowan Williams, former Archbishop of Canterbury and now Master of Magdalene College, Cambridge

Martin Laird is an American Roman Catholic writer who has published several quite short but profound books in Christian prayer and meditation. His latest, An Ocean of Light: Contemplation, Transformation, and Liberation (Oxford University Press) is perhaps his best yet. It analyses the three kinds of mentality we bring to bear on our prayer – 'reactive', 'receptive' and 'luminous', showing how the grace of the Spirit gradually makes us more open to God's love, less defensive, more deeply patient. It is written with simplicity, but with a lot of helpful reference to the long tradition of thinking about prayer and contemplation. I found it a real gem.

Peter Lynas, Director of the Evangelical Alliance UK

I find myself regularly recommending two recent books which really help Christians navigate the current cultural context. The first is Tech-Wise Family by Andy Crouch, a book I put off reading for six months because I knew it would change how I did things. Crouch has written extensively on culture, but this is a simple, practical book about small changes that can make a big difference. The book invites us into habits and rhythms in which technology serves our calling rather than becoming an idol. The second book is A War of Loves by David Bennett - the unexpected story of a gay activist discovering Jesus. What struck me most is that David is not trying to win an argument, but ultimately inviting people to consider what is true, and so to encounter Jesus. He tells his story in a way that will be accessible to anyone, gay or straight. He is always pointing beyond himself, asking what is love and who should be the object of our love.

Ruth Gledhill, former Religious Affairs Correspondent for The Times and now Online Editor of The Tablet

One of the most helpful books I read this year was Ronald Rolheiser's Domestic Monastery (DLT). Everyone attempting to live a life on a spiritual level understands the value of retreats, silence, meditation. But for many of us, realising any of these states can be extremely difficult, as fitting them around work and family and friends is not at all easy and sometimes actually impossible.

All my working life, I have viewed my work, as a Christian journalist, as a form of service to God. But until I read this book, it had not occurred to me to regard home also as a form of religious life. The term monasticism conjures up many stereotypes, most of which do not fit in with the uxorious reality of happy domesticism.

Yet in fact there are parallels. The urgent demands of the school bell, the need to have dinner on the table for hungry young things, can indeed be like the monastic bell, a form of summoning to prayer. And the withdrawal from a previous active social life of going out to theatre, cinemas and dinner for the many years of raising young children can be isolating and lonely, but here it becomes more an opportunity to reflect and grow spirituality, indeed like being on a retreat.

In his characteristic beautiful and forgiving style, Rolheiser gently raises eyes from the humdrum of the home, helping to see it as an additional vocational experience, a giving to God in its own right. I hope and believe this has the potential to make me a better wife and parent, moving into 2020.

Rob James, Baptist minister and media adviser to the Evangelical Alliance Wales

I've always had a concern for the Jews. Who wouldn't given the treatment they've received from so-called "Christian Europe" over the past two thousand years, not to mention their current experience of antisemitism. I completely understand their desire for the land they call their own. The creation of the state of Israel back in 1948 was a very understandable response to their suffering and their longing to return home.

At the same time, I have an equal concern for the Palestinian people. My heart aches for those who have been dispossessed and are unable to return to the land they regard as their rightful home too. It's a very complex and heartbreaking situation.

Like so many others, many far wiser than me, I continue to wonder how this particular circle will ever be squared. But I was offered a glimmer of hope when I was given a copy of an amazing book entitled The Anteater and the Jaguar.

The author, Rayek Rizek, who was born in Nazareth in a Palestinian Christian family, is an active member of the exciting initiative known as 'Neve Shalom/Wahat al-Salam' (The Oasis of Peace), which he describes as the "only community inhabited by choice by Palestinian Arabs and Jews in the whole of Israel/Palestine".

"Members of our community," he says, "are among the very few in the general population who are wholly open to discussing every issue that has to do with the Israeli-Palestinian conflict, past, present and future. Tensions exist in our oasis, but they go with the territory so to speak. They bring teachable moments. They are for us fodder for enlightenment."

The Anteater and the Jaguar is an extremely honest and hugely encouraging book, and given the unique initiative it describes, it deserves to be read as widely as possible.

David Baker, rector of the churches of East Dean, Friston and Jevington

Have you ever experienced the "betrayal barrier"? This was not a term I had come across until a few months ago. But circumstances we were facing as a family led me to pick up a book I had not previously known, entitled When God Doesn't Make Sense, by James Dobson. And it describes the "betrayal barrier" as a sense of "extreme disappointment after we have relied on God to look after us". In his introduction to the book, RT Kendall writes: "I reckon that most Christians, sooner or later, feel that God betrays them or uncaringly lets them down in some way."

However, this book is not filled with warm platitudes, soppy soundbites, 'name it and claim it' promises for victorious living, or indeed pop psychology. It is soaked with Biblical wisdom. Suffering, the book argues, can teach us things nothing else can teach us. That said, Dobson is always aware that theological answers alone may well not "take away the pain and frustration we experience when we journey through spiritual no-man's land". So if life seems painful and baffling right now, read 'When God Doesn't Make Sense'. It won't provide all the answers – and that, in a way, is precisely the point. But the book will provide you with a sympathetic companion to take just one step forward in the desert.

Dr Joe Aldred, broadcaster, ecumenist and responsible for Pentecostal and Multicultural Relations at Churches Together in England

I got through several interesting books during 2019, but the one that I found most interesting and recommend as a worthwhile read is Frank Viola and George Barna's Pagan Christianity? Exploring the Roots of our Church Practices. These authors warn readers to be prepared for a rude awakening as they find out how off track our current religious practices are. And they mean every word of it!

From the buildings we worship in and their architecture, to the sermon we preach; from the eucharist and how we celebrate it, to the altar at which we kneel; from the Sunday school class we sit in to the choir we sing in - plus a host of other religious practices carried out week in and week out around the world - Viola and Barna assert a lack of biblical rootedness for what goes on in churches.

For me, their most telling case is that the modern church has become institutionalised, replacing the dynamic organism found in the early church of the apostles that operated by way of each and every member playing a living role in the Body of Christ. Whether there will ever be the non-hierarchical, non-ritualistic, non-liturgical organism or ekklesia these writers call for, is debatable.

What is not debatable in my opinion is that the professionalisation of the modern church service has tended to lead to the diminishing of the involvement of the so-called laity. Arguably this calls into question the principle of the equal importance of every member of the body of Christ, something that was evident in the highly interactive and participatory, non-conformist Pentecostal church I grew up in.

Dr Irene Lancaster, Hebrew scholar and former teaching fellow in Jewish history at Manchester University

This year has been a bonanza spent reading Israeli and British political biographies. But my book of the year is Charles Moore's three-volume authorised biography of Margaret Thatcher. Like Thatcher herself, Charles Moore understands the importance of both the big picture and of detail. The book explains Thatcher's gift for encouraging the aspiring lower middle classes. In the 1980s, so many young people in my area of Liverpool gave up the habits of a lifetime and voted Conservative. The book also reveals how Thatcher was betrayed in the end. In a very English coup, her male colleagues didn't kill her – they simply promised things and didn't deliver. At a time when academic historians are rightly held in contempt, it is to journalists that we will now have to turn for the truth. And through his trilogy, Charles Moore, a former editor of The Telegraph, has performed a service to the memory of our greatest peace-time Prime Minister.

Kay Morgan-Gurr, Chair of Children Matter and Co-Founder of the Additional Needs Alliance

I've liked Ann Voskamp's writing for a while, including the fact that her books are available in an audible format, when many great books I want to 'read' are not (I'm partially sighted). It's the most digitally highlighted book I own and contains wisdom that will help many and last the test of time. The title to her book The Broken Way and its subtitle - A daring path into the abundant life - may seem at odds with each other, but like many, I already knew this secret.

Drawing from her own experiences and those of her friends, Ann takes you through the importance of suffering, the voicing of it and the need to sit with others in that suffering. She brings out the gold hidden within it and the need for the church to take note, to welcome and recognise the grace and dignity held within the process of suffering.

She challenges the notion of standing alongside those who are suffering being just a difficult task we must do and points out the fact that this 'sacrifice' in itself is sacred – thus the abundance is shared.

Ann relates everything back to the cross, the suffering Christ, and weaves it through the book as choosing to live a 'Cruciform Life'. She does this not in a soft and fluffy way but in a gritty, honest and at times a punch to the gut way. I know I will want to listen to this book again just in case I missed something the first (or second) time!

David Robertson, commentator and evangelist at Third Space in Sydney

Douglas Murray's latest book, The Madness of Crowds, published by Bloomsbury, is already causing a stir – and rightly so. In fact if there is one book I would urge you to read this year, Murray's would be the one. Subtitled Gender, Race and Identity, it does what it says on the tin. Murray has four large chapters entitled 'Gay', 'Women', 'Race' and 'Trans', and they are separated by three interludes on 'The Marxist Foundations', the 'Impact of Tech' and 'Forgiveness'. The writing is excellent, there is much new information and the reasoning is clear and devastating.

Although writing from his own perspective, it is clear that Murray has a lot of time for, and appreciation of, Christianity. In fact there are times when he expresses a biblical understanding better than some popular Christian authors. The interlude on forgiveness is one of the most beautiful, insightful and moving pieces of writing I have read in years. Murray points out that the collapse of the barrier between public and private language, and the situation that technology has got us into, means that forgiveness has become an even more necessary but rare phenomenon.

We have still retained the Christian concepts of guilt and shame, but have lost the means of forgiveness and redemption that Christianity offers. We either offer forgiveness only to those people we like (thus enhancing the increasing tribalism in society) or we bow to the pressures of the mob. We go along with the dogmas of the progressive elites: 'no questions allowed. No questions asked'.

You will almost certainly not agree with everything Murray writes, but he will challenge, stimulate and cause you to think. As a Christian, this atheist caused me to weep and pray. At a time when so many Christians are compromising with the culture in order to 'win it' – and thereby losing both the culture and the church – it is wonderful that the Lord gives us a gay atheist who sees and speaks truth!