The Catholic Church, Nazis and responsible broadcasting

The BBC has promised to edit one of its podcasts, in response to complaint from a listener who felt that the content conflated the Nazis and the Catholic Church.

The BBC Sounds podcast "Nazi on Trial, part 1: Can'just following orders' justify horrific crimes?" explored the escape of Adolf Eichmann, so-called 'Architect of the Holocaust', from Germany to Argentina with the help of old allies and the Catholic Church.

This was advertised as containing educational material, and formed part of a series produced in partnership with the Open University on the theme of 'Bad People'.

The listener was prompted to complain by the following exchange between the two presenters:

Dr Julia Shaw, a psychological scientist at UCL: "[Eichmann] fled to Italy where the Catholic Church helped him with a passport and visa, which is really messed up, and then he eventually reached Argentina. And so Eichmann later said that the organisation of his escape had gone like clockwork."

Sofie Hagen, a comedian: "F***ing cowards. F*** Eichmann, f*** Josef Mengele. Help from old allies? F*** your old allies. F*** the Austrian Alps, f*** chicken farms. I hate everything. F*** these guys – I include the Catholic Church in that."

Dr Julia Shaw: "Fair."

Sofie Hagen: "I really hate these people."

In response to the complaint, the BBC has now agreed to edit out the reference to the Catholic Church.

Why is all this important?

Rights and responsibilities

Without the freedom to criticise and insult religions and their adherents, the fundamental right to freedom of expression – currently much embattled in the UK – would mean very much less in practice.

There is no right not to be offended.

Neither is the BBC entirely alone in allowing the Catholic Church to be equated with the Nazis: it has since been joined by Minskaya Prauda, official newspaper of the Belarusian capital, in their recent cartoon.

But there was a serious reason behind the presenter's tirade, namely the role of some Catholic clergy in aiding many Nazis in their post-war escape from justice, through networks known as the Ratlines.

What exactly was the relationship during this period between the two groups - the Nazis and the Catholic Church?

Ratlines

The 'Bad Person' under the microscope in this particular episode was Nazi war criminal Adolf Eichmann, one of the principal engineers of the Holocaust, who evaded prosecution at the end of the war by emigrating to Argentina.

In his book Hunting Evil, Guy Walters describes how Eichmann was helped by a Franciscan priest, Fr. Edoardo Domoter, to assume the false name in which he was then issued with a travel document by the Red Cross.

Perhaps the most notorious clerical accomplice in such activity (though not mentioned in the 'Bad People' podcast) was the Austrian Bishop Alois Hudal, rector of the German college of further priestly studies in Rome.

According to Walters, Hudal later wrote of having provided false identity papers to prisoners, and of feeling "duty bound after 1945 to devote my whole charitable work mainly to former National Socialists and Fascists, especially to so-called 'war criminals'".

The BBC made a serious contribution to public understanding on this subject in its 2018 Radio 4 series 'The Ratline', written and presented by human rights barrister Professor Philippe Sands QC and based on his book with the same name.

According to Professor Sands, Hudal assisted the escape of other infamous Nazis such as Josef Mengele, Erich Priebke and Franz Stangl. He denied having helped Eichmann, though Walters reports that at one stage Hudal had been issuing Domoter with travel documents.

Walters recounts how in 1960 Eichmann was famously tracked down in Argentina, abducted by Mossad agents, brought to public trial in Israel and finally executed in 1962.

What did the Vatican know?

Was the Pope at that time aware of the complicity on the part of certain priests and bishops in effectively perverting the course of international justice?

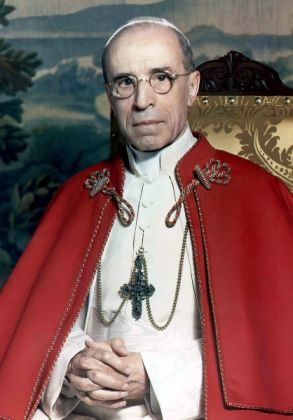

When reporting on the opening by Pope Francis in March last year of Vatican archives on the papacy of Pius XII, the BBC appeared to resist any such firm conclusion: "Historians still have many questions about the notorious 'ratline' - an escape route facilitated by some Catholic clergy who helped Nazi war criminals flee to South America after the war."

These archives are at last enabling in-depth research into alleged failures by Pius XII to oppose the Holocaust.

Walters reveals that Eichmann himself later wrote: "It was odd how throughout my escape journey I was helped by Catholic priests ... In their eyes, I was just another human being on the road."

However, Walters has dismissed as "complete tosh" the idea that the Vatican as an institution aided Eichmann's escape.

Bishop Hudal himself, in his memoirs published posthumously (as Römische Tagebücher – "Roman Diaries"), complained bitterly and at great length about his forced resignation as rector in 1952, which the Vatican had said was at the insistence of Pius XII, and which he was told resulted from certain cardinals' opposition to his reported pro-Nazi sympathies.

Another escape network

In any balanced appraisal of the part played by Catholic clergy during this period, it's difficult to ignore a network of a very different kind, known as the Rome Escape Organisation, which operated from the very heart of the Vatican – in fact from inside the Holy Office, nowadays known as the Congregation for the Doctrine of the Faith.

Its joint leaders were Monsignor Hugh O'Flaherty of Killarney and, from November 1943 onwards, escaped British PoW Major Sam Derry.

In his book The Vatican Pimpernel, Brian Fleming recounts how O'Flaherty and his associates found hiding places for PoWs, Jews and other civilian refugees including anti-Fascist partisans, in religious houses, apartments and other locations in and around Rome. These fugitives were supplied with food, clothing, money and sometimes counterfeit documents through a complex network of supporters who lived under the constant danger (which sometimes tragically turned into reality) of discovery, torture and execution.

Unofficial support came from the British Embassy to the Holy See, then working from inside the Vatican.

Astonishingly, one of the earliest sanctuaries used by Mgr. O'Flaherty was his own residence, the Catholic German College next door to the Vatican - a different college, however, from the one of which Alois Hudal was rector.

O'Flaherty was vulnerable to seizure when liaising with fugitives and supporters outside the Vatican precincts. Fleming describes one assassination attempt in March 1944, ordered directly by Gestapo chief SS Obersturmbannführer Herbert Kappler.

To evade capture, the Monsignor often went about disguised variously as a street-cleaner, postman or labourer, while at other times enabling Allied PoWs to adopt the garb of Monsignori - a novel form of camouflage.

Some of these activities were depicted in a film, The Scarlet and the Black, starring Gregory Peck as O'Flaherty and John Gielgud as Pius XII, based on the book with that title by P J Gallagher.

At the Liberation in June 1944, O'Flaherty's organisation was (again according to Fleming) sheltering over 3,900 escaped PoWs, many hundreds of others having already been extracted to neutral countries or back to Allied lines. In total, around 200 hiding places were in operation during early 1944.

An episode of the BBC's This is Your Life in 1963 was planned to celebrate the life of Hugh O'Flaherty, but because of his frail health at that time was instead based around that of Sam Derry. Mgr O'Flaherty was however able to appear on the programme, aired shortly before his death.

Righteous Among the Nations

Several priests and nuns are mentioned by Fleming as members of the Rome Escape Organisation, including Sister Maria Antoniazzi, originally from Morecambe, whose contribution is described on the BBC website.

Sister Maria is one of over 60 other Catholic clergy and religious sisters in Italy alone who have been enrolled as Righteous Among the Nations by the Yad Vashem World Holocaust Remembrance Center in Jerusalem. Other examples are Mgr Vincenzo Barale, and Sisters Ferdinanda and Emerenziana of St Joseph's School in Rome.

Although evidence about Mgr O'Flaherty's role has also been submitted to Yad Vashem, Fleming tells us that the monsignor was very reticent about his wartime activities, and that "not nearly as much is known" about his work for an estimated 2,000 civilians as about that on behalf of servicemen, for which he was honoured by several Allied nations (including the UK which awarded him a CBE).

A recent documentary by Deutsche Welle presents viewers with a Vatican document held by Yad Vashem, which records that "4,715 Jews were found shelter in the Vatican and other Catholic institutes during the German Occupation of Rome".

Fleming suggests that most of these would probably have been given refuge not through Monsignor O'Flaherty but via DELASEM, the Jewish Community's own Delegation for the Assistance of Jewish Emigrants.

During the Occupation, DELASEM appointed a Franciscan friar as acting president - Fr Pierre-Marie Benoit, now also Righteous Among the Nations.

In wartime Florence, a rescue operation for Jews was facilitated by the archbishop of the city, Cardinal Dalla Costa, whilst another in Assisi was inaugurated by the bishop there, Giuseppe Placido Nicolini. Both have been honoured as Righteous by Yad Vashem.

Paying tribute to another of the priestly Righteous, Don Francesco Brondello, the Raoul Wallenberg Foundation concludes: "Whilst the Catholic Church has often been criticized for its tacit acceptance of the Nazi deportation of Jews, a clearer picture of Italy's underground network of saviors – which allowed the majority of the 45,000 Jews residing within the Italian border to be rescued – seems to suggest that the majority of the survivors owed their lives to the Catholic clergy."

That so many of Rome's Jewish population were able to avoid capture in the first place was attributed by Adolf Eichmann to delays in rounding them up caused by protests emanating from the Vatican.

The Raoul Wallenberg Foundation also document the measures taken by a Vatican diplomat in Turkey, Monsignor Angelo Roncalli (later Pope John XXIII) to enable the escape of Jews from occupied Europe, sometimes using false visas and baptismal certificates.

Responsible broadcasting

The series of BBC podcasts on 'Bad people', as explained in another linked episode (Part 2 of "Nazi on trial"), aims to "try and understand why humans act badly without dehumanising them".

But the presenter's reference to the Catholic Church appears - pending the promised edit - if anything more likely to foster rather than tackle prejudice, and to distort rather than promote understanding, by dehumanising religious believers today based on the abhorrent actions of some Catholic clergy over 70 years ago.

Perhaps our public service broadcaster may be wise to bear in mind that, when purportedly trying to understand and prevent prejudice against one group of people, expressions of irrationally generalised hatred could risk generating - even appearing to legitimise - prejudice against other groups.

During a question and answer session in the concluding programme of his series (at 14 minutes in), Professor Sands issued this sobering warning: "We can see that we're on the cusp of some sort of return [of a fascistic mentality] – it's not the same thing ... but it's pretty plain that you can see elements emerging that are essentially to do with the demonisation of the other. We see it in this country, I think – we're beginning to see it – in which certain people are being targeted not because of what they're doing or have done, but because they happen to be part of a group ...".